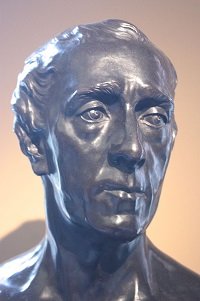

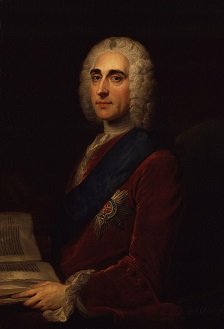

Philip Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield

Philip Dormer Stanhope, heir to the Earldom of Chesterfield, was born on the 22nd September 1694. He was a child of a family who had been part of the British aristocracy for centuries. One of his ancestors had been executed by Edward VI’s advisors for his role in a plot to overthrow the child king, while his grandfather (also named Philip) had killed a man in a duel during the reign of Cromwell and fled to France, then managed to get a pardon from the King in exile Charles II and return to London in triumph with the restored monarch in 1660. One of his grandfather’s cousins was James Stanhope, a soldier who went into politics and who became a mentor figure to young Philip. After a brief period of study at Cambridge, with the help of James he was elected as MP for a rotten borough in 1715. [1] As was (and is) traditional he gave a maiden speech in Westminster to mark his entry into Parliament. Once he had finished another MP stood up, congratulated him on the speech, and then informed him that by giving a speech in the Houses of Parliament while under 21 he had committed an offence that carried a £500 fine. As a result Philip left the house, and indeed the country, though he didn’t give up his seat.

Philip set off on a tour of Europe, a traditional thing for a young noble like him to do. In Paris he gathered news of a planned Jacobite rebellion in England and sent it back to his uncle James, who was the senior Secretary of State for George I. How much aid this was to his uncle’s successful quashing of the rebellion is difficult to say, but James does seem to have been grateful for his grand-nephew’s help. Philip returned to England and to the Commons in 1716. In 1717 his uncle became First Lord of the Treasury, and if the position of Prime Minister had existed at the time it would have been his. He got Philip a position as one of King George I’s “gentlemen of the bedchamber” – noblemen who served as private servants to the King. The role was highly sought after as it put them right at the King’s ear, and was seen as a stepping stone to great political influence. So it would prove for Philip.

At the time King George I and his son, the 33 year old Prince George, were at odds. The Prince was popular with the people – a lot more popular than his father. This caused the older man to resent him, and this came to a head following the birth of the Prince’s second son, George William, in 1717. At the christening the Prince got into an argument with one of child’s godparents, the Duke of Newcastle. The King blamed Prince George for the quarrel, and banished him and his wife Caroline from the court. However he did not allow their children (including the infant George William) to go with them. Both parents were extremely worried about him, and they did manage to sneak in at least once to see him. In February 1718 the three-month old George William fell ill, and the King relented and allowed his parents to return. Within a few weeks the infant prince was dead. Though a post-mortem showed that his death was caused by a heart defect his father still never forgave the King for his actions.

Philip, as a member of the royal household, found himself right in the middle of this rift. It was a tricky tightrope to walk – on the one hand, he did have to maintain loyalty to the King but on the other he knew that the Prince would himself be King one day. He managed to thread the needle by becoming friends with the Prince’s mistress, Henrietta Howard. Henrietta was one of Caroline’s Ladies of the Bedchamber (a female counterpart to Philip), and Caroline was not only aware of her relationship with her husband but approved of it. She knew that her husband would keep a mistress regardless, and she’d rather it be one that she got along with. Through this connection Philip managed to keep a foot in both camps.

Philip’s father died in 1726, and Philip inherited the title of Earl of Chesterfield. This entitled him to a seat in the House of Lords, but he didn’t take it up until the following year when King George I died and he was released from the royal household. This left him in a strong position politically, and he became a recognised face in Parliament. In 1728 he was made the ambassador to the Hague, a position which he held for two years and in which his charm and skill won him the gratitude of the British government, the Order of the Garter, and a mistress of his own. Elizabeth du Bouchet was a French governess, descended from Huguenot refugees, working for a Dutch family of his acquaintance. She wasn’t a great love of his life – he had several other mistresses. However she was the only one to bear him a son, the only recorded child he ever had. When Chesterfield returned to England in 1732 he brought the pregnant Elizabeth with him. The boy, named Philip after his father, was born in 1732.

In 1733 Chesterfield was married to Petronilla Melusina von der Schulenburg, an illegitimate daughter of King George I. He may have married her as a favour to the royal family, as there were rumours that she had borne an illegitimate son a few years earlier. Around this time he also quarrelled with Robert Walpole, the Prime Minister. Walpole hoped to imposed an excise tax on wine and tobacco to aid the country’s finances, but the extreme unpopularity of the bill led to many who had previously been loyal to Walpole opposing it. Walpole eventually had to drop the bill, but he dismissed any who had spoken against it from their positions. At the time Chesterfield was Lord Steward of the Household, a prestigious cabinet post, but Walpole stripped him of the office. As a result Chesterfield quit the Whig party and went into the opposition, leading it for several years.

It was around this time that Chesterfield created what would turn out to be his unwitting literary legacy – a series of letters to his illegitimate son. He began writing the letters when his son was only five or six years old, though the majority were written between the boy’s fourteens and twenty-second birthdays. They consisted of advice meant to guide the young man, who Chesterfield had come to realise would probably be his only heir. The advice was generally pretty good – Chesterfield spoke of the wisdom of only showing as much of your learning to others as would match their learning, for example. Some of it (such as “Whatever is worth doing all is worth doing well”) has effectively become proverbs. On the other hand, he had a low opinion of women – one notable quote was:

Women are much more like each other than men: they have, in truth, but two passions, vanity and love; these are their universal characteristics.

It’s ironic then that while Chesterfield was sending these letters his son was in the process of falling in love with the woman he would spend the rest of his life with. Philip the younger was travelling in Rome (part of the traditional “grand tour” of the classical world financed by his father) when he met Eugenia Peters (or Pieters). She was also from London, two years older than the eighteen-year old Philip. She wasn’t considered attractive, but she was intelligent and well educated, and young Philip seems to have fallen deeply and irrevocably in love with her. From the contempt his father had always shown his mother, he knew that he would not approve the relationship. In fact he would probably force him to break off the liaison on threat of disownment. Still, he kept in touch with Eugenia when they returned to London.

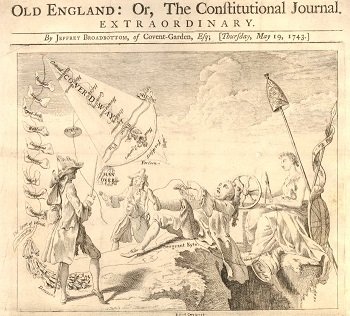

While he was writing the letters to his son, Philip senior was neck deep in the politics of Parliament. He led the opposition against Walpole for several years, but ill health saw him on a sabbatical in Europe in 1742 when Walpole “fell from power”. (In truth he handpicked his successor and effectively retained control of the government.) As a result he remained in opposition and became a thorn in the side of the crown and the government. In 1743 he founded a new magazine called “Old England; or the Constitutional Journal”. This magazine was essentially a mouthpiece for those like him who had expected to rise when Walpole fell, and had been disappointed. The most notorious of its writers was “Jeffrey Broadbottom”, an obvious pseudonym. Some even identify Chesterfield as the author of Broadbottom’s essays, though more credible attributions are the two editors, James Ralph and William Guthrie. In fact it’s quite likely that the Broadbottom articles were written by multiple people and some even point to the novelist and playwright Eliza Haywood (who was writing political articles under her own name at the time) as a possible member of the Jeffries. Still, whichever fingers held the pen it’s pretty clear that it was Philip Stanhope’s voice that Jeffrey Broadbottom spoke with.

Walpole’s health began to fail in 1744 (he died early the following year), and with him losing control the successors he had chosen fell from power. They were replaced with a coalition government that has been dubbed the “Broad Bottom administration” as it essentially followed the pattern that “Old England” had dictated. The most lasting legacy of this was that it established that the control of government was dependent on controlling Parliament, and not on Royal decree. [2] No longer excluded, Chesterfield was sent to to negotiate with the Dutch and secure their support in the war with France over the succession to the throne of Austria. When he succeeded he was rewarded with the job of Viceroy of Ireland, which he took up in January of 1745. He proved to be both an excellent administrator and a master of the diplomacy needed to balance between the various factions in Ireland. In fact he was so even-handed and respected that when Charles Edward Stuart invaded in August and the Jacobites in England and Scotland rebelled, the Irish chose not to join them. There were some fears that they would however, leading to an incident where a servant burst into Chesterfield’s bedroom one morning to announce “the papists are rising!” Chesterfield’s response was characteristically witty:

I am not surprised at it, why, it is ten o’clock! I should have been up too, had I not overslept myself.

Chesterfield’s other great contribution to Ireland was his decision to open up Phoenix Park to the public. The Park had been created eighty years earlier as a deer-hunting preserve for the King, but the Hanoverians had little interest in deer hunting and so the park had simply become a drain on the public purse. Chesterfield’s decision to open it as a public park was hugely popular with Dublin residents, and the main road through the park is named Chesterfield Avenue after him. In November of 1746 he handed over the job to a distant relation of his named William Stanhope, while he took on William’s job of “Secretary of State for the Northern Department”. This position saw him responsible both for the Northern part of England and for Britain’s relationship with the northern countries of Europe, such as the Dutch and Germans. It was the type of job he’d been trying to get for decades, but he only held onto it for less than a year and a half. In February of 1748, officially due to his worsening deafness but unofficially doubtless due to political manoeuvring, he resigned and retired to the back benches of Parliament.

Chesterfield mostly retired from politics after this, though he did still have a few pet projects. One of these was the push to modernise the British calendar. Though the Catholic states of Europe had adopted the Gregorian calendar (complete with leap years) in 1582, Britain had remained on the Julian dates. Even more confusing, the beginning of the year was set as the 25th of March – meaning that the day after 24/03/1749 was 25/03/1750. To add more confusion, while Scotland used the same Julian calendar their year began on the 1st January. The Calendar Act of 1750 (known as the Chesterfield Act) set out to resolve this confusion. The first step was to fix the issue with starting the year, so 1752 began on the first of January. (This meant that 1751 was only 282 days long.) More controversial was the next step – removing eleven days from the calendar. The third to the thirteenth of September 1752 were completely excised, and so Britain was finally “brought up to date”.

Chesterfield’s other pet project was his son, who he purchased a seat in Parliament for in 1754. This was an attempt to overcome the stigma of Philip’s illegitimacy by allowing him to show his quality in Parliament – something which failed due to Philip’s complete lack of talent for public speaking. After this failure Chesterfield secured him a diplomatic post at Hamburg. Philip took up the post in 1756, went home on leave in 1759, and never returned. This may have been because of his blossoming relationship with Eugenia. In 1761 she had a son, named Charles. She had a second in 1763, named Philip after his father and grandfather. In 1764 Philip (the middle one) was appointed as British envoy to the court of Saxony in Dresden, a job which eventually necessitated him giving up his seat as an MP. Here he was visited by the great Scottish biographer and diarist James Boswell, who recorded how Philip brought him to court to introduce him to the King. As the court was in mourning and Boswell had no appropriate black garb, the two men agreed on a subterfuge where Boswell pretended to be a British officer in uniform. This seems to have been a bonding experience, and Boswell took a great liking to him.

I really love Stanhope. He and I were might well together. We agreed to renew our acquaintance in London.

Sadly Philip never returned to London to take Boswell up on his offer (one which would have brought him into the orbit of Samuel Johnson and quite possibly made him a much more notable figure). His health began to fail due to some unknown disease in 1766, and he was granted a leave of absence. Eugenia and his sons came out to stay with him, and he and Eugenia were married in Dresden in 1767 before they moved to the south of France for his health. Philip died in Avignon in 1768 due to dropsy caused by his illness. He was only 36 years old.

The popular story is that Chesterfield only became aware of his daughter-in-law and grandsons after his son’s death. If this is true, he seems to have been glad of the discovery. He took them under his care, though as the children of an illegitimate heir neither of his grandsons could inherit his title. Instead Chesterfield followed the British tradition of adopting a distant relative in order to get a heir. [3] This cousin (also named Philip) became the fifth Earl of Chesterfield in 1773 when Philip Stanhope passed away, aged 78 years old. His will caused some controversy, as he had left his two grandsons an annuity of £100 each and an inheritance of £10,000 held in trust. That level of inheritance for illegitimate heirs was almost unheard of. However it was the will’s treatment of Eugenia that would have the greatest impact on Chesterfield’s legacy.

Simply put, Eugenia got nothing. No pension, no bequest, no means of support whatsoever. It was a shocking omission, and one which left her with no apparent means of support. But Eugenia did have one option open to her – one which may have struck her as fitting revenge for Chesterfield’s contempt. She had the letters that he had written to Philip over the decades. She approached a publisher, and the letters were published as Letters to His Son on the Art of Becoming a Man of the World and a Gentleman in 1774. The book was a smash success, selling out printing after printing. Helping the sale was the controversy – the letters had never been intended for general viewing, and Chesterfield’s frank expression of his views on women (which included seduction tips for his son, as well as open discussion of the benefits of adultery) led Samuel Johnson saying that:

They teach the morals of a whore, and the manners of a dancing-master!

Naturally, there was a great deal of backlash against Eugenia for putting this dirty linen out in public. Several pamphlets denounced her as a profiteer, and acted as if she was personally responsible for what Chesterfield had written, and should have edited out the “immoral” passages. However as time went on the letters became more associated with their author than with their publisher, and Eugenia was able to fade back into financially comfortable obscurity. Meanwhile the Letters made Chesterfield’s name a byword for rakish behaviour. The protagonist of Samuel Pratt’s “Pupil of Pleasure”, a young would-be rake who seduces his way across England, bases his philosophy on quotations from the “Letters”. Even Charles Dickens took inspiration from them – his villainous MP in Barnaby Rudge, Sir John Chester, takes his name from Chesterfield. It seems ironic that a man like Philip Stanhope, who based his entire life and career around his public speaking, should in the end be defined not by that but by things he had written. He never thought that the letters would be his legacy, but it goes to show how little anyone can control how history will see them, in the long run.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] A “rotten borough” was an electoral district which had the right to send members to Parliament, but which also had an extremely small number o voters and so could effectively be bought or controlled. St Germans (the borough where Philip was elected) had less than ten voters who between them elected two MPs.

[2] Though to this day the leader of the party who controls Parliament is “asked” to form a government by the monarch.

[3] And hired William Dodd the Macaroni Parson to be his tutor.