Harriet Tubman, American Hero

Harriet Tubman was born as Araminta Ross in Dorchester County, Maryland, sometime around 1822. The exact year is debatable – nobody bothered recording it, as nobody in authority really cared exactly when a slave baby was born. Because that’s what Minty (as everybody called her) was. She was property. Her parents were property. Her grandmother had been kidnapped in Africa, made into property and shipped halfway round the world. From the moment she was born, Minty was told that that the natural order was for black people to be property, and for white people to own them. Her father Ben belonged to a man named Anthony Thompson, and ran his plantation for him. Her mother Harriet belonged to a woman named Mary Brodess, and when Mary died Harriet was inherited by her son Edward, along with the rest of her property. Of course, none of this was the real truth. People can’t be property – not really. But the white people of Dorchester County convinced themselves that it was possible, and their unfortunate slaves suffered for that delusion.

Minty was first put to work as a slave when she was five years old, when she was hired out as a nursemaid. She recalled later how she was ordered to keep the baby’s cradle rocking, to hold it in her arms if it fussed, and on no account to let the babe cry out. Every time it did, she was whipped. This was how at the age of only five she received her first scars. She was barely fed in this job, and became so weak she had to be sent home. Still she continued to be hired out to jobs like that until she was twelve years old, and old enough to work in the fields. Though this was back-breaking labour, Minty still far preferred it to being forced to obey every whim of a white woman as a domestic servant. She was trusted enough to go to the store for her masters, something which led to near disaster. One day she was at the store when an overseer spied a slave who had entered without permission. The overseer tried to grab the slave to whip him, but Minty (using the subtle passive resistance that became second nature to the people forced into this unnatural servitude) managed to get herself in his way and allow the slave a chance to escape. The enraged white man grabbed a heavy iron weight off a shelf and threw it, either at Minty or at the other slave. Whatever his intention, it caught Minty on the side of the head and severely injured her.

The weight broke my skull and cut a piece of that shawl clean off and drove it into my head. They carried me to the house all bleeding and fainting. I had no bed, no place to lie down on at all, and they laid me on the seat of the loom, and I stayed there all day and the next.

Her master tried to sell her, rather than be bothered with looking after her, but nobody wanted to buy a teenager with a cracked skull. The laws that protected slaves (such as they were) meant that he couldn’t let her die, and so Minty was slowly nursed back to health. She was never the same though – and not just because of the scar on her head. She had fits of unconsciousness (probably epilepsy caused by brain scarring) and vivid hallucinatory dreams. She’d always been religious, but these visions further deepened her faith. Her God was not the God of the New Testament, who condoned slavery through acceptance. Nor did she believe that she and her kin had been cursed by God for the behaviour of Noah’s son Ham, as some of the preachers insisted, making their slavery a divine punishment. No, Minty believed in a God who liberated slaves, who broke chains, who delivered the enslaved to the Promised Land. The God that Minty believed in was the God of Moses, and she believed in him with all her heart.

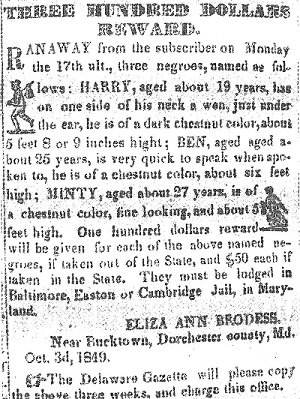

In 1844 Minty was married, to a free black man named John Tubman, and took his surname. The pair had no children – possibly a conscious choice on Minty’s part, as she knew they would (by law) inherit her status as a slave. John may have hoped to save up enough money to buy her freedom, though that would have been difficult to do. Minty may not have been worth as much as most slaves, due to her illness, but it was still far beyond what John could earn. Minty lived with the constant knowledge that at any time she could be sold and sent anywhere, without a moment’s forewarning. Three of her sisters had been sold as children, despite her mother’s wails, and she had been told she would never see them again. [1] She faced the same fate, as by 1849 her master was actively bringing potential buyers to view her. His death that year (which she felt guilty about, as she’d prayed for it to happen) temporarily disrupted the process, but she knew it was only a temporary reprieve. His widow was soon trying to break up the estate and sell the “assets” (enslaved human beings included). Minty realised that she had to take matters into her own hands.

There was one of two things I had a right to, liberty or death; if I could not have one, I would have the other.

Minty’s first attempt at escape was with her two brothers, Harry and Ben. They were younger than her, and less determined to escape. Though their escape was publicised and a reward offered, it wasn’t recapture but rather cold feet that doomed the escape. The two men decided to return, and Minty had no choice but to go along. When she made her escape a second time, she went alone. However she didn’t just rely on her own resources – this time she went along the Underground Railroad. The Railroad was a loose network of slaves, former slaves and abolitionist allies from cities like Philadelphia, who helped runaways like Minty find sanctuary along the way. Of course, as the Railroad was an illegal organisation records of its activities are few and far between, and it’s only mostly thanks to Harriet Tubman herself that we know as much as we do. She recounted how she took shelter at one house, who had her hide in plain sight sweeping the yard before they hid her in a cart and moved her on. She travelled 90 miles to freedom, mostly on foot, mostly at night, following the North Star.

[God] set the North Star in the heavens. He gave me the strength in my limbs. He meant I should be free.

Harriet finally had her freedom. It was around this time that she abandoned her given name of Araminta, and took her mother’s name as her own – possibly as a confusion tactic for those hunting her, possibly to honour her family, possibly as a way to signify her freedom by finally choosing her name for herself. While she was finding her feet in Philadelphia, the stakes were raised for escaped slaves with the Compromise of 1850. The Compromise was originally designed to diffuse tension over the status of California, New Mexico and Utah. They had been captured from Mexico in the Mexican-American war, and the gradually coalescing pro- and anti-slavery states saw them as potentially shifting the balance of power between them. The Compromise was an attempt to avert civil war by allowing California to become a non-slave state, while allowing the new Territories of Utah and New Mexico to independently choose their status. (Neither chose to allow slavery.) In return for these concessions, Congress passed a new “Fugitive Slave Act”, which bound the authorities even in those states which did not allow slavery to assist in the capture and return of runaway slaves. In a stroke, there was no true sanctuary for escaped slaves in America south of the Californian border.

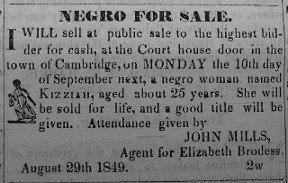

While Harriet was trying to figure out whether to head to Ontario (as many American blacks, both former slaves and free blacks fearful of their safety, did) she received news that would change the course of her life. She had a niece named Kessiah, though the two were close enough in age that they had been raised as sisters. Kessiah had even named her baby daughter Araminta. Now the word reached Harriet that Kessiah and her two children were going to be sold out of state, tearing them away from her husband and family. Harriet made the decision that her freedom was meaningless without putting it to use, and headed back into the hell she had escaped to become a legend.

When Harriet made it to Baltimore she hid out with Tom Tubman, brother of her husband Ben. (Ben had stayed behind when she ran away, and had actually tried to persuade her not to go.) Tom was a valuable ally, but Harriet had another – one equally as motivated as her to help Kessiah escape. John Bowley was Kessiah’s husband, a free black man who had had been born a slave but had been freed in the 1840s. He was willing to risk his freedom to help Harriet, as if they had been caught he would almost certainly have been killed or re-enslaved. Their plan was carefully laid. While Harriet secured an escape route in Baltimore, John attended the auction, perhaps pretending to be bidding on behalf of a fictional master. As planned, he managed to get the winning bid on Kessiah and her children. Of course there was no way he could afford to pay the money, but by the time the auctioneers realised this the Bowley family were long gone. They sailed a canoe up the river to Baltimore, where Harriet took them along the Railroad to Philadelphia, and from there to Canada. They had found their freedom, and Harriet Tubman had found her calling.

When I found I had crossed that line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person. There was such a glory over everything; the sun came like gold through trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in Heaven”

Harriet’s second trip was to rescue her brother Moses and two of his friends, though it was she who took him to the promised land. Moses became her nickname and she became one of the most enthusiastic conductors on the Underground Railroad. She didn’t act alone – others who helped her included free blacks living in the area, white Quakers whose religious beliefs led them to defy slavery, and others of conscience. Harriet’s crusade nearly came to an early end on her third trip in the autumn of 1851, when she tried to contact her husband Ben and persuade him to come north. She found out that not only had he no wish to leave, he’d actually remarried. Harriet was tempted to storm into their house and make a scene, but she knew it’d be too much of a risk – more than he was worth. Instead she decided to gather all the local slaves who desired freedom, and wound up leading a group of eleven (possibly including one of her brothers) out of perdition.

Many of Harriet’s exploits have been embellished, but there’s no denying her impressive accomplishments. Between 1850 and 1861, she made 13 trips into Maryland. She rescued around 70 people herself, and gave almost as many instructions on routes that they used to escape. She carried a pistol on her trips, though there’s no record of her firing it. In fact the only time she’s reported to have used it was when one o the slaves she was rescuing got cold feet and tried to turn back. Harriet drew her gun and gave him a choice – go on or die. He chose to go on. Another weapon in Harriet’s arsenal was her singing voice – she used spirituals (a version of hymns that used African singing patterns) to keep people hiding in her boats or carts appraised of danger. A change in her tempo indicated danger, and warned them to keep on hiding.

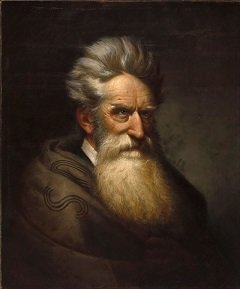

Harriet’s name was well-known enough in abolitionist circles that she was approached in 1858 by John Brown to help him with something he was planning. Twenty years earlier, when an abolitionist preacher he admired was murdered by a mob, Brown had decided to dedicate his life to fighting slavery. In the previous four years he had been a notorious figure in “Bleeding Kansas”, where pro- and anti-slavery forces fought pitched battles that claimed many lives, including that of Brown’s son Frederick. John Brown was planning to take the battle outside of Kansas, and to ignite a slave revolt across the whole of the South. The spark he planned for the tinder was a raid on the United States arsenal at Harper’s Ferry in Virginia, just over the border from Maryland. This would provide the weapons to arm the local slaves, and begin the general uprising. Harriet’s knowledge of the surrounding territory was invaluable to him in planning his attack, and she also used her contacts to help him recruit a force to attack the fort. Ill health prevented her from joining him in the attack on the 16th October 1859, which was probably lucky for her. Though Brown’s men succeeded in capturing the armoury, they failed to spark the revolt they’d been counting on and the response of the authorities was faster than they’d thought. The men were surrounded, trapped, attacked and either killed or captured. John Brown was hanged on the 2nd of December, defiant to the end.

The outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 brought an end to Harriet’s expeditions into Maryland, but it also raised the hope that soon they would no longer be necessary. She volunteered for service, at first acting as a nurse in Port Royal (a captured city in South Carolina). However she was frustrated by Lincoln’s initial unwillingness to take a fully abolitionist position.

God won’t let master Lincoln beat the South till he does the right thing.

On the first of January 1863, Abraham Lincoln did the right thing. The Emancipation Proclamation declared the freedom of every slave in the disputed territories – three million men, women and children all finally recognised as not property but people. There were celebrations in Port Royal – as it was within the ten states that had revolted against the Union, it was covered by the proclamation. [1]

Harriet moved from her support role to the frontlines of the war in 1863. She served as a “scout” (and spy) for the Union forces. Her contacts let her recruit from former slaves, who could still blend in fairly well behind the Confederate lines. Naturally it’s difficult to track such covert efforts, but the most notable of them was her guidance of the Raid at Combahee Ferry in June of 1863. There she guided a troop of 300 soldiers in an attack that freed 750 slaves. It was a huge propaganda coup, not least because the troop was almost entirely composed of freed former black slaves. (The sole exception was their leader, an old ally of John Brown’s from “Bleeding Kansas” named James Montgomery.) Though the newspaper reports didn’t mention Harriet by name, they referred to her as:

[T]he black woman who led the raid and under whose inspiration it was originated and conducted. For sound sense and real native eloquence her address would do honour to any man, and it created a great sensation.

For the rest of the war Harriet continued to serve as scout, spy, recruiter and nurse for the Union Army. In April 1865 the Confederates surrendered, and a few months later Harriet headed home. On the way one ugly incident reminded her that the end of slavery didn’t mean the end of prejudice. Harriet was in a train travelling to New York when a conductor told her that no blacks were allowed in the non-smoking carriages. Harriet protested that she was a civil war veteran, but the conductor accused her of lying and then (aided by two other passengers) physically forced her out of the train car. In the process they broke her arm and two of her ribs, while the other white passengers cheered them and urged them to throw Harriet from the train. Instead of arriving home a hero, Harriet arrived home an invalid. To add insult to (literal) injury, when she wrote to the government seeking the back pay and military pension her service should have entitled her to, she was ignored. So too were several of her friends and allies who wrote to politicians. Harriet never received official acknowledgement of her service.

Harriet’s injuries, combined with a recurrence of the old troubles from her head injury, left her bedridden for several months. She was forced at first to rely on the charity of her friends, but luckily for Harriet there were many who knew exactly how much they owed her. In addition, Harriet made two new friends who would have a profound impact on her life. The first of them was Sarah Bradford, a writer who was a neighbour of hers. Both were around the same age, and despite their class differences (Sarah was white, and the widow of a judge) they became friends. Sarah had heard of Harriet’s war stories, and wanted to hear them for herself. She realised the importance of Harriet’s experience, and decided to write a book based on her interviews with Harriet. The book, Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman, was released in 1869. It was groundbreaking – both for its honest depiction of Harriet’s struggle for freedom, and for showing a black woman in such a heroic light. It became a worldwide bestseller, and made Harriet Tubman famous. Since Sarah was honest enough to direct the profits to Harriet it also ensured her financial stability for a while.

1869 was a banner year for Harriet, as that same year she remarried. Her new husband was named Nelson Davis, a civil war veteran 22 years her junior who she had met through her charity work. The two adopted a baby girl named Gertie in the early 1870s. Nelson suffered from tuberculosis, and this meant that he was often unable to work. Harriet never stopped trying to help those less well off than herself, and though Sarah Hopkins’ book brought in some money she still had to work for a living and take in boarders in order to make ends meet. Two of those boarders offered her a way to improve that situation, claiming to know where a Confederate store of $5000 in gold had been hidden before the end of the war. They offered to guide Harriet to the location for $2000 in cash, but it turned out to be a scam. Harriet borrowed the money and met the men, but was chloroformed and robbed. The matter became a huge news story, and the renewed publicity led to a pair of Republican congressmen introducing a motion that she be paid for her services during the war. The bill didn’t pass.

In 1886 Sarah Bradford wrote a second book about Harriet, based on further conversations and to help her financially once more. The book reignited interest in Harriet and made her a public figure again. The death of Nelson in 1888 [3] and the fact that Gertie was now grown up left Harriet at a loose end. It was around this time that the Women’s Suffrage movement was gathering momentum, and there was a considerable crossover between those fighting now for women’s rights and those abolitionists who had supported Harriet in the Underground Railroad days. In the 1890s Harriet became more involved with the movement, who immediately seized on her as an example of a bona fide female American hero. Harriet became so well known that she was the keynote speaker at the first meeting of the National Association of Colored Women, [4] and was a speaker at many suffragette meetings. It was at one of these that she made possibly her most famous quote:

I was a conductor of the Underground Railroad for eight years, and I can say what most conductors can’t say — I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger.

Harriet’s long running headaches due to her brain injury were somewhat alleviated in the late 1890s by a trepanning operation in Boston, relieving the pressure on her brain. As a result her health improved considerably. In 1903 Harriet donated some her farmland to a local church to make a home for the aged (though she was angry with the church that they charged a $100 entry fee, as she’d wanted it to be a charitable venture). The home opened in 1908, and in 1911 Harriet was admitted as a resident. In 1913 she died, ninety years old and over sixty years free. She was buried with partial military honours, an acknowledgement of the service that had never been fully recognised. At the unveiling of a plaque in her honour, mayor of her hometown of Auburn said:

Born as she was in the obscurity of slavery and bound by its shackles, the memory of this woman should be an object of reverence to every member of her race, and the example of her achievement an inspiration to every member of our great nation.

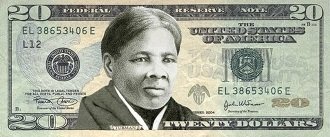

Harriet had been famous during her lifetime, but in death she became a legend. Over the years her story grew, and the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s embraced her as a precursor and inspiration to their struggle for acceptance. Countless American schools are named after her, and there are statues of her throughout America. Her home in New York State was made a museum in the 1920s. In 1995 her religious devotion throughout her life was recognised by the Episcopal Church, who added her to their calendar of saints. And in April of 2016 the US government announced that Harriet Tubman was going to receive an even more unique honour – after a public vote, she was chosen to replace Andrew Jackson on the $20 bill. Harriet will be the first woman in over a century to appear on US currency, and the first African-American in the country’s history to be so honoured. A fitting tribute to the heroic woman who was once dismissed as “damaged goods” by the people who thought they owned her.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] If you think that she accepted that, you may not have heard of Harriet Tubman before.

[2] Legally the Proclamation could only apply to the battlefield, under Lincoln’s authority as Commander-in-Chief. As a result only 75% of the slaves in the USA were freed by it. Slavery didn’t officially end in the US until the Thirteenth Amendment was passed nearly three years later.

[3] As Nelson was a veteran, his death meant that Harriet was finally given a military pension – not in her own right, but as a war widow.

[3] A suffragist organisation formed due to racist elements in the main suffragette organisations trying to exclude black women from the movement (and potentially exclude them from getting the vote at all).