The Apache Kid, Soldier and Outlaw

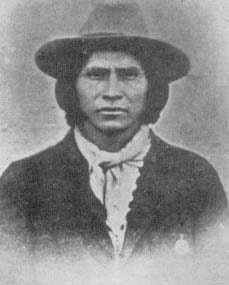

Even the true name of the Native American man known as Kid, and later called The Apache Kid, is lost to the mists of his legend. The most commonly given one is “Haskay-bay-nay-ntayl”, [1] and it’s possible that most of the others we have are simply misspellings of that. The next most common seems to be Skibenanted, which is reasonably close. The one written in the legal records (though not by Kid himself) was Hahouantell, which is also relatively close. Still, with the confusion his name engendered it’s clear why he preferred to be known to white men simply as “the Kid”.

The Kid was born around 1860, somewhere in southeast Arizona. He was the grandson of the chief of his tribe, a man named Togodechuz. There’s a popular story that the Kid was captured by the Yuma tribe as a child and rescued by US soldiers, becoming an orphan raised in the Army camps. However this does seem at odds with some of the later facts of his life. Another story has it that his family settled in the town of Globe in Gila County in 1868 – an impressive feat, as Globe wasn’t founded until 1875. Globe was on the lands belonging to the San Carlos Apache Reservation though, so it’s entirely possible his family were living there in 1875 when prospectors found a large circular silver nugget, and a mining town sprang up around them overnight. (Luckily for the peace in the area the silver was played out within four years, though the copper alongside it was enough to keep the town going.) [2]

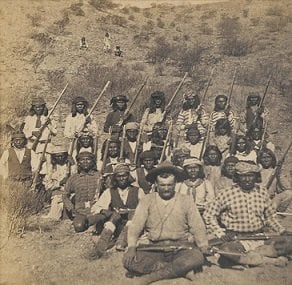

At some point the Kid became acquainted with Al Sieber, a German immigrant who was Chief of Scouts for the Army. The rank was an unusual one that basically put Sieber in charge of the Native American scouts who were hired on a short term basis by the Army to help them track and deal with other native troublemakers. (Of course, there was never any question of making any Native American a full soldier.) Sieber was reportedly very impressed by the Kid’s tracking skills, athleticism (he was most noted as an amazing runner) and leadership abilities. He encouraged him to enlist as a scout. In 1881, aged around 21, the Kid enlisted. By 1882 he had been promoted to Sergeant (the highest rank available to one of his ethnicity), and over the next five years he would renew his contract repeatedly. His status grew within the company and he even married the daughter of an Apache chieftain named Eskiminzin.[3]

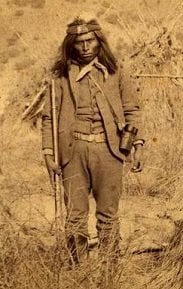

During his time as a scout, the Kid took part in several battles of the long-running series of conflicts called the “Apache Wars”. The exact battles he took part in are hard to pin down, given the ad hoc nature of his service. It’s known that he travelled to Mexico several times, possibly as part of General Crook’s 1883 expedition to retrieve and arrest Geronimo. He certainly accompanied Crook on his 1885 expedition to retrieve the runaway chief once more, as there he wound up getting into serious trouble. Details are scant, but he was involved in a drunken riot as one of the drunken participants. He was given the relatively light sentence of a $20 fine, on condition that he be sent back to America.

This blot on his record doesn’t seem to have done his career much harm. In fact, getting out of the Geronimo hunt before General Nelson Miles took it over in 1886 was probably a good thing. General Miles got Lieutenant Charles Gatewood (a long term liaison with the Apache scouts) to negotiate Geronimo’s surrender. Then he denied Gatewood the credit under a flimsy pretext (claiming Gatewood had disobeyed orders by approaching Geronimo with too small an escort). Geronimo was sent to join the rest of his tribe in exile in Florida – along with any Army scouts who belonged to the tribe. They had been promised that they would be exempted for their service, but Miles broke the promise and sent them into exile anyway.

The series of events that led to the Kid’s downfall began in 1886. It’s important to realise that despite some in the Army’s perception of the Apache scouts as a fungible resource, the truth was that they were actually composed of multiple different “bands”. Broadly speaking these were subdivisions of tribes, which were in themselves subdivisions of peoples like the Comanche. The Kid belonged to the “SI band” of the Aravaipa tribe, and his wife (and father in law Eskiminzin) belonged to another band, one labelled by the white officers as the “SL band”. A member of a third band (the “SA band”) named Rip killed the Kid’s grandfather Togodechuz. (Or possibly killed Togodechuz’s son, the Kid’s father – accounts vary). Why he did it we don’t know. All we know is that he escaped retribution, until the day the Kid decided to drink tiswin.

Tiswin is a drink made from corn, potently alcoholic. It was a vital component of many tribal rituals, but it had been forbidden (along with all other alcohol) on the reservations. Being kept from performing tiswin rituals was one of the reasons chiefs like Geronimo had left the reservations. It was also forbidden to the scouts, but in May 1887 Sieber and the other officers left their camp on official business. The Kid was left in charge, and he and the other scouts decided to make tiswin. Whether this was just in order to fuel a drunken party, or whether it was part of some ritual to honour his deceased relative, we don’t know. All we know is that as a result of this, the Kid left the camp and with five other scouts tracked down and killed Rip. The press painted this as a drunken rampage, though other sources suggest that it was part of a retributive ritual that the Kid couldn’t carry out until he got the tiswin. In the end, it doesn’t really matter. The Kid had killed a man. Worse, in the eyes of the army, he had done it while AWOL.

When Al Sieber and the other officers returned to the camp, the Kid and his men were prepared to surrender and face punishment for their absence. They knew they were unlikely to be punished for killing Rip. Internal Native American justice such as this was informally winked at. So the men would simply hand in their weapons and face the music. Unfortunately, the negotiator for the officers was a man named Antonio Diaz. He disliked the Kid, and saw this as an opportunity to undermine his standing with the scouts. During the discussion said that the Kid and his men should surrender, or else all the Apaches would be sent into exile in Florida. Whatever his intention was, it heightened tension among all the scouts present, and someone in the crowd opened fire. After that it was just confusion and mayhem. When the dust settled, there were no casualties. But a bullet had shattered Al Sieber’s ankle, and the Kid and fifteen of his comrades were gone.

Two cavalry troops were sent out to track the escapees, but the Kid and his comrades managed to evade them for two weeks. The newspapers got hold of the story and spun it into a general condemnation of the whole “Indian Scout” program, with the usual racist diatribes attached. Ironically it was the scouts in the cavalry troops who managed to locate the Kid. Though a raid on his camp failed to capture any of his group, the army did manage to seize their horses and supplies. The Kid knew that long term survival would be hopeless without those and sent messages out to agree surrender terms. Once the cavalry had pulled back from active pursuit, half of the runaways handed themselves in on the 22nd of June. With that accomplished peacefully the other half, including the Kid, surrendered on the 25th.

The majority of the runaways were actually let off the hook for their part in the fracas, but an example had to be made. The Kid and four others were charged in a court martial with mutiny and desertion. The penalty was death by firing squad, but this was commuted to life in prison. General Miles, possibly due to a petition by Al Sieber, intervened and had this reduced to ten years. The Kid and his four followers were sent to Alcatraz in January 1888. The mortality rate for Native Americans in prison was extremely high, due to a combination of disease and prejudice-fuelled violence, so the five men were extremely lucky that in October 1888 their convictions were overturned. The case had been reviewed by the Judge Advocate General’s Corp, and they had decided that since most of the officers involved in the court martial had been outspokenly anti-Native American then there was no way to consider it an unbiased court. The verdict was declared null, and the five men were set free.

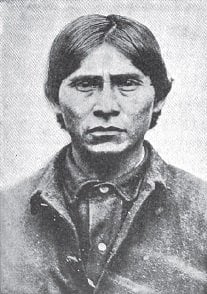

The Kid returned to Globe, and tried to live a peaceful life. Many in the military were unhappy with his release, and they were even less happy when a lawsuit brought by the Indian Rights Association the following year led to the release of all Apaches being held as federal prisoners. Public outcry was immense, and Glen Reynolds, sheriff of Gila County (where Globe is located), was quick to sense an opportunity to garner some political capital. He realised that the Kid’s military acquittal did not prevent a separate civil charge being brought, and so he had arrest warrants sworn out for the arrest of the Kid and three other men for the “attempted murder of Al Sieber”. The four were swiftly convicted by a jury who had already made up their minds on the issue, and were sentenced to seven years in the infamous Yuma Territorial Prison.

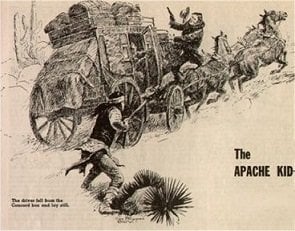

The four, along with four other Apaches and a Mexican, were part of a prisoner transport from Globe to Yuma personally escorted by Sheriff Reynolds. At the start all eight Apache prisoners were chained and shackled in the transport wagon, but at Kelvin Grade the trail became too steep for the fully loaded wagon. Seven of the prisoners were unchained and set to walk behind the wagon, with only the Kid and one of the other prisoners, a man named Hos-Cal-Te, kept inside. Almost as soon as the wagon started moving the six Apaches attacked one of the guards, William Holmes, and managed to get hold of his rifle. They shot all three, killing Holmes and Reynolds. [4] The survivor was the driver, Eugene Middleton. One of the other Apaches lifted a rock to finish the driver off, but the Kid stopped him. Middleton eventually managed to stagger into town and get medical attention. The Mexican, Jesus Avott, a horse thief who hadn’t been considered dangerous enough to be shackled, fled at the first shot but went to the nearest town to get help. Jesus Avott received a pardon for his actions. The Kid’s magnamity was less well received – the death of a county sheriff was a serious matter. The incident became infamous as the Kelvin Grade Massacre.

The press went wild with the news that “The Apache Kid” (as they called him) was on the loose. A massive manhunt began. Those related to the Kid were persecuted – his wife was sent to a reservation in Alabama, while his father in law Eskiminzin was interned in prison without trial to prevent him aiding the Kid. The ordeal proved too much for a man in his sixties, and though he was released in 1894 he died soon after. Al Sieber set the Apache Scouts on the trail of the eight renegades. Five were killed by their pursuers, while two (Hos-Cal-Te and another called Say-Es) were captured. They received life sentences for murder, though both died within five years of tuberculosis. A five thousand dollar bounty was placed for the Apache Kid, dead or alive. It was never claimed.

Over the next few years, any raid by Apaches was laid at the feet of the Kid. Some reports accused him of raiding the reservations to kidnap Apache women, while others had him attacking any traveller who was alone on the plains. Any other Apache renegade, like the former associate of Geronimo named Massai, was assumed to be part of “the Apache Kid’s gang”. Naturally the writers of dime novel Westerns loved him, and he became a stock villain of their narratives. There’s no definite idea of the Kid’s ultimate fate, and how and when he died is entirely unknown. In a shootout in 1890 between a Mexican Army unit and a band of Apache raiders, one of the Native American casualties was found to have Glen Reynold’s pistol and watch. But the man was too old to be the Kid. An old comrade of his, army scout turned bounty hunter Mickey Free, [5] claimed to have tracked and killed the Kid. He was unsuccessful in claiming the bounty. In fact pretty much anyone who managed to kill any Apache raiders claimed that the Kid was among those they killed. The most well attested of these was in 1906, when a posse led by local ranchers managed to kill the leader of a band of raiders. Though it’s not certain if it was the Kid they killed, in memory of the event a local mountain was named Apache Kid Peak, and eventually that entire area of San Mateo Mountains was officially named the Apache Kid Wilderness.

One of the US Cavalry soldiers who hunted for the Kid was the future novelist Edgar Rice Burroughs, famous for creating Tarzan among other characters. In 1933 he wrote a novel called Apache Devil. Despite the title it’s actually one of the most notably sympathetic portrayals of the plight of the Apache people, exploited and betrayed to the point of breaking. There’s a lot of the Kid in the hero of the novel, the titular Apache Devil. As for the Kid himself, around the same time there were reports that he was still alive, with it being claimed that he had returned to Gila County to visit his relatives in 1935. We’ll likely never know the true end to the story of the Apache Kid, and I don’t think we’d ever really want to. Legends, real ones, never die.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] The translation of that as “Tall Man Destined For Mysterious End” seems far too ridiculously on the nose to be genuine.

[2] Another resident of Globe who has featured in this column was Pearl Hart, last lady outlaw of the Wild West.

[3] Eskiminzin had a history steeped in tragedy. In 1871 he had led his band to take a government offer to settle down and become landed farmers in the area around Camp Grant near Tucson. Some local white settlers, motivated by racism and opposed to this attempt at assimilation, led a group of Mexican bandits and hostile Pima tribesmen to attack the settlement. They massacred 144 of the residents (including 136 women and children), and took 29 children captive to sell into slavery in Mexico.

[4] Some sources say that they didn’t actually shoot Holmes, but that he died of a heart attack during the struggle.

[5] Mickey Free himself played an important role in the history of the Apaches. Born Felix Tevelles, his kidnapping as a twelve year old by the Apaches led to an Army unit capturing the family of the Apache war leader Cochise and holding them hostage against the boy’s release. Cochise’s murderous retaliation eventually spiralled into the opening battles of the Apache Wars. Mickey was adopted and raised by one of the Apaches, and wound up serving with the Apache Scouts as an interpreter.