“Is that you, John Wayne?”: Michael Herr’s Dispatches and the Vietnam War

“I was seduced by World War Two and John Wayne movies”

-Anonymous Veteran in Mark Baker’s Nam: The Vietnam War in the Words of the Men and Women Who Fought There (1981), p. 12.

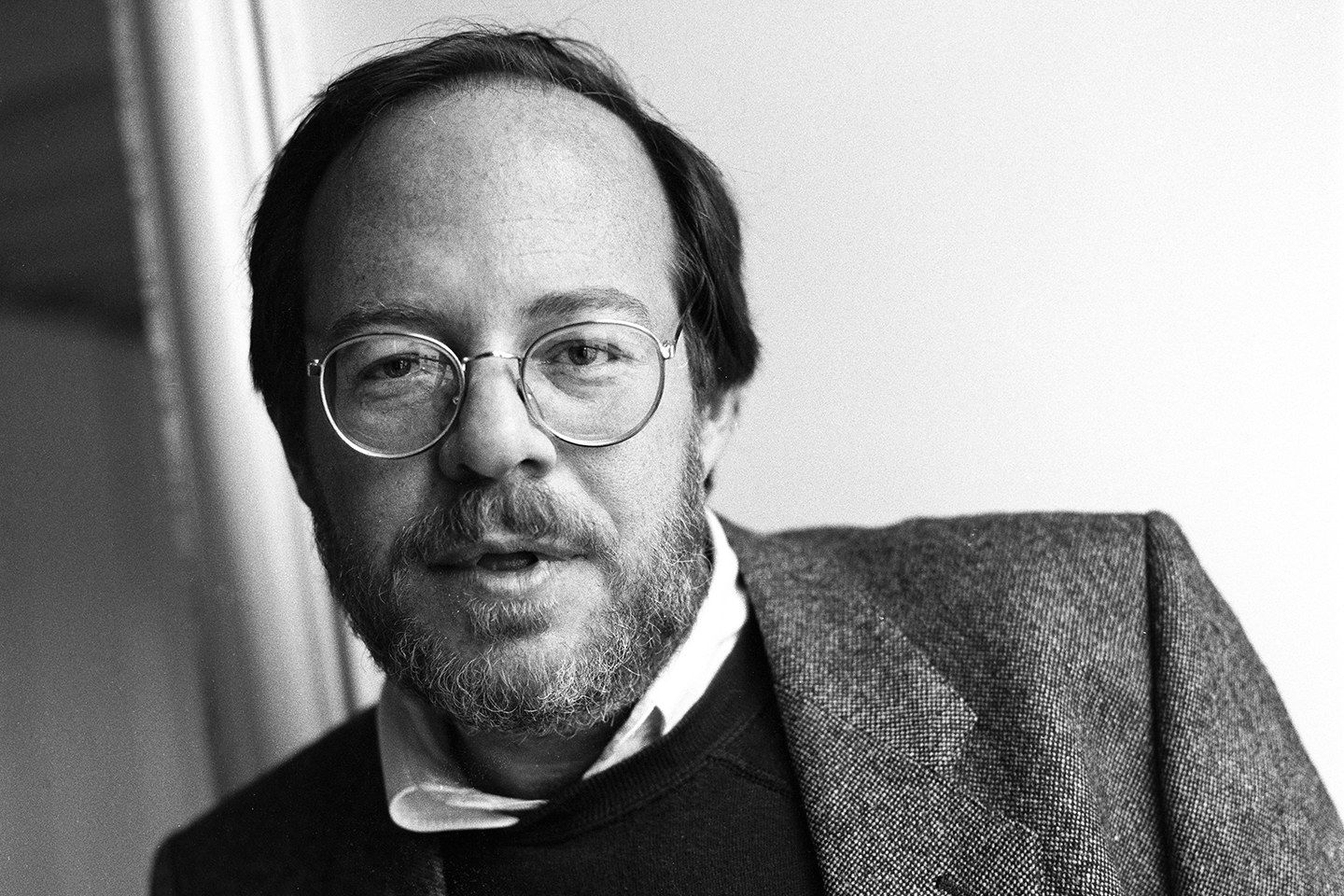

On June 23rd, screenwriter and Vietnamese War correspondent Michael Herr passed away aged 76. Co-author of such screenplays as Apocalypse Now (1979) and Full Metal Jacket (1987), he will be a familiar voice to many cineophiles owing to his distinctly terse, almost hard-boiled detective-like internal monologue in Francis Ford Coppola’s epic, and his hyper-sexualized poetic style in Stanley Kubrick’s work. A writer less keen on the development of plot, his main-strength lay in the psychoanalysis of characters. Jungian in this approach, he tended to obsess over a subject’s duality; their struggle to remain sane as an internal conflict erupts between the civilized self and the primitive self. Granted, it is not exactly an alien concept in the world of cinema. But in the context of journalism, it set him apart from those of his peers who were also in Vietnam during the late-1960’s.

And yet, his staunch refusal to adhere to any journalistic norms can be understood when one realizes that Herr fell into the role of war correspondent by pure accident. In 1967, at the age of twenty-seven, he took on a writing assignment for Esquire, which was to do up a light-hearted, albeit critical piece on the Americanisation of Saigon in South Vietnam. A film critic for the New Leader beforehand, this new job was supposed to be a stepping stone in his career, a means of gathering together sufficient experience and material in order to hence write a book of lasting substance. However, by 1968, that situation was no longer the case. Neither Herr, nor the US Army were going to find what they initially sought out to obtain.

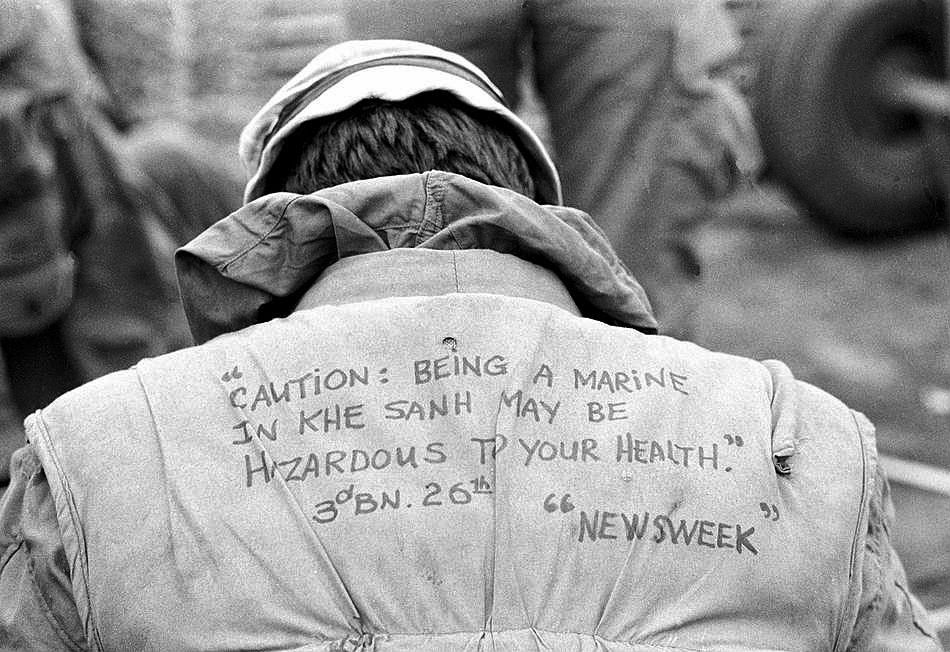

Beginning with the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong’s launching of the Tet Offensive on January 30th, followed then, the next day by the VC’s seizure of the US Embassy in Saigon, this new assault altered the course of the war dramatically. On top of this rapid onslaught, a US outpost in Khe Sanh found itself besieged by the NVA, leading to the infamous Battle of Khe Sanh, which ran from January 21st to July 9th, 1968.

By the battle’s conclusion, the US army had suffered 205 deaths and over 1,600 injuries, while the NVA death toll amounted to 1,602 confirmed kills by the US Marines, though the unofficial number could have been as high as 15,000. This calamity in turn would cause American public support for the Mission to decline at an accelerating rate, and as the stark new reality dawned, Herr came to accept that the war could no longer be covered as he had originally intended.

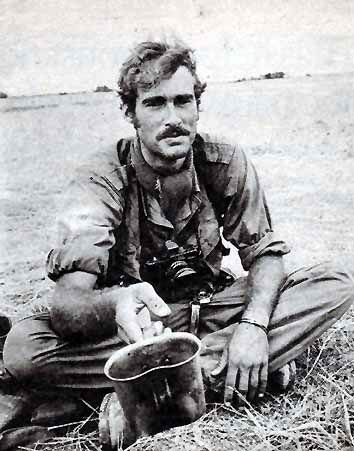

“The war only got wackier, even more deadly”, wrote the photographer Tim Page, a colleague of Herr’s. In order to survive, this pair, along with photojournalist Sean Flynn deemed it somewhat necessary to embrace the hell. One article became four sprawling visions of a debauched macho netherworld. A couple of months became two years, and as Herr gathered more and more notes, a larger idea came into being. Vietnam would not inspire Herr’s book, Vietnam would be the book.

Departing in 1969, Herr worked towards having his essays released the following year. Six went by however, the delay caused by the onset of severe depression requiring psychiatric treatment. Still, in spite of his personal trauma, Herr was embraced during this period. In 1975, his Esquire writings gained him wider attention when they were included in Tom Wolfe and E.W. Johson’s reportage anthology, The New Journalism.

Then, in 1977, a decade after first setting foot in Vietnam, his field reports, revised and expanded, were published under the title Dispatches. A book-length work of reportage, which harrowingly ventured into a psychedelic warzone constructed by youthful fantasies, well-spun propaganda and perversions liberated through carnage, Dispatches was as much about post-war life as it was about his life in the war. Reflecting upon his days with Esquire, the book succeeded in enlightening the uninformed as to the complex nature of post-traumatic stress, and the inability of those stationed in Vietnam to ever fully escape from that world mentally. Once a person was in a “world of shit”, they were effectively there for life.

For Herr, this fact becomes increasingly evident as one assesses his body of work taken whole. Truth be told, he did not seem willing or able to extricate himself from Vietnam properly. Besides penning a few pulpy crime novels, and receiving additional screenwriting credits, thematically he seldom strayed too far from Dispatches and by the 1990’s, his output had become as sparse as a wasteland. Eventually withdrawing from media and publishing in 2000, his final credit was a short biography on Stanley Kubrick, entitled Kubrick was originally printed in Vanity Fair across two issues.

In saying this, to see his post-Vietnam years as a prolonged period of misery alone would be to oversimplify his life. Often when giving interviews, though he would note the horrors of the war, his recollections were not entirely bereft of fond memories either.

[iframe id=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/4DMbq0TuSqs”]

At once, appalled by the spectacle of the American Dream in such a bestial form, so too was he excited by how the mission exposed this twisted side. This was the dualism which intrigued him, and in it, he found his own personal contradictions. Here was a man openly opposed the invasion, writing with a view to show the violence and uncover the war’s “secret history”.

But, simultaneously, he was in Vietnam to satiate another longing: to live within the depraved pornography of the destructive Mission. The Vietnam he entered was one of pure unadulterated fantasies, the male mind reverting to a place free of grey areas. Enabled by state-of-the-art weaponry, mind-altering substances, wildly distorted rock ‘n’ roll, scenarios ripped from the screens of Hollywood’s million dollar productions and street-walking women passed around like “communion”, he did not shy away from mentioning that the experience was just as life-changing because of its exhilarating kicks. Indeed, he is not a lone voice in expressing such views. War veteran and screenwriter William Broyles Jr wrote, in a 1985 Esquire article entitled ‘Why Men Love War’, that it was a place of rebellion and freedom, an “escape from the everyday… bonds of family, community [and] work”.

“I was into it”, Herr would recall in later years. “I was all caught up in the trip… One is never bored… I was drawn to it by my own violent and adolescent emotions.”

Growing up in Syracuse, New York, in the book he remembers, as an example of these “adolescent emotions”, reading a Life Magazine war report, which featured images of dead bodies. On these, he wrote:

“I could have looked [at the pictures] until my lamps went out and I still wouldn’t have accepted the connection between a detached leg and the rest of the body”

Likening the images to “first porn”, being both real and unreal simultaneously, this divide between fact and fiction is one of the regular themes in Dispatches. Vietnam, as he saw it, was a media war, a spectacle, vicious and glamorous, entertaining and disturbing, real and surreal. Bodies were strewn across paddyfields, Jimi Hendrix and Rolling Stones records were blaring from every base, some grunts would announce that they were only there to “kill gooks”, others would send home the ears of murdered civilians to their girlfriends, shocked then to learn that this was why they were broken up with. And as this all unraveled, film crews and news teams were sending back sanitized reports to appease those on the home front. It was no wonder that when the war ended, the veterans endured an enormous backlash. According to Herr, the truth was not told, because the standard narrative was overwhelmed by facts and statistics, which gave a picture, but not the whole picture.

Dispatches, on the other hand, bypassed factual reporting and veered towards what Bavarian director Werner Herzog might term “Ecstatic Truth”. This hyper-realistic ethos in documentary film-making favors people above general themes in order to extract illuminating truth. As Herzog said it himself:

“If I were only fact based… the book of books then, in literature, would be the Manhattan phone directory. Four million entries. Everything correct. But it dusts out of my ears and I do not know: do they dream at night? Does Mr. Jonathan Smith cry in his pillow at night?”

Herr as a documentarian of the war is not to be valued for his ability to churn out facts, or regurgitate official US military lines unless, of course, they are up for a lampooning. Dispatches is not read in order to understand what happened in Vietnam factually. The reality is manipulated. Interviewees are sometimes tweaked, or fabricated. The purpose was to capture the mood, the tensions, the fear and excitement, the deeper, varied motives of the Marine Corps and how these often stood in direct opposition to the Mission’s overall objective.

“Conventional journalism could no more cover this war than conventional firepower could win it”, he declared. Convention would dictate that the army was to be seen as a monolith. If such was the case, then the daily military briefings on the roof of the Rex Hotel in Saigon, dismissively dubbed the Five O’Clock Follies, would the main source of honest information. The Follies, Herr dismissed as “[an] Orwellian grope through the day’s events as seen by the Mission”. They were, according to Richard Pyle of the Associated Press, “the longest-playing tragicomedy in South-East Asia’s Theatre of the Absurd”, defined by euphemisms, white lies and faceless body counts. All the trains ran on time, all the troops were fighting to destroy the Commies and for every setback, there was always a reason to feel good about the war.

“Well at least they died for a good cause”, says Private First Class “Rafterman”, as he looks down at the lifeless bodies of two Marines in Full Metal Jacket, his character a metaphor for the military’s communications branch. “What cause was that?”, comes the voice of Sergeant “Animal Mother”. “Freedom?”, Rafterman replies, with uncertainty, to which, Animal Mother responds by saying: “Flush out your headgear new guy, you think we waste gooks for freedom? This is a slaughter, if I’m gonna get my balls blown off for a word, my word is poontang.”

[iframe id=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/LqpGiwNtMvY”]

In order to challenge the Orwellian speak, Herr had to become an Orwellian writer, receptive to the cleanliness of nuanced communicative language, and ready to write down what the Marines said, omitting none of the filth or frankness. The Follies said what people wanted to hear. He had to show what they needed to see. The Khe Sanh beamed into living rooms was not besieged, the Marines were merely “encircled”. The base was not suffering endless assaults, the base was hygienic and its men were “clean”. The Official line, which the news repeated “could be understood by newspaper readers quickly, it breathed Glory and War and Honoured Dead”. But because of this, the story “wasn’t being told for the grunts… [They] were going through all of this and… somehow no one back in the world knew it.”

The media glut of digestible glory, so thick he termed it a “communications pudding”, “spawned a jargon of such delicate locutions that it’s often impossible to know even remotely the thing being described”, although this ignorance suited readers just fine:

“Most Americans would rather be told that their son is undergoing acute environmental reaction than… shell shock, because they could no more deal with the fact of shell shock than they could with the reality of what had happened to this boy during his five months at Khe Sanh.”

“I’ll tell you why I’m smiling”, said one injured Marine to Herr, “but it will make you crazy.”

In her article, ‘What It Was Like’, written for the Columbia Journalism Review, Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Connie Schultz paid Herr a debt of gratitude for explaining where the bravery and glory of the war’s earlier years had gone. Schultz was living in Ohio, the state with the fifth highest death toll, which amounted to 3,094, and the scars of Vietnam were evident in her community daily:

“The rest of our boys came home, but the ships never righted. Guys I’d known my entire life weren’t fun or funny anymore… I’d look at my friends’ older brothers sitting on the front porches and their stares would scare me… [It was] as if they thought I was trying to start a fight just by smiling at them.”

Unable to fully grasp why they were acting in such a manner, it was only after she acquired a copy of Dispatches in 1978 that the reasons became apparent. It was, she said, “260 pages of reasons why [my parents] sent me away to college… [C]ollege kids were special, they got away with things. Like war for example.”

During the war, third level education meant an immediate pass on military service when the draft lottery was active between 1969 and 1972. In 1985, a government study found that the period between 1966 and 1972 had the highest rate, on record of men enrolling in college. Back in 1960, the attendance of men, between the ages of 18 and 24 was at 24%. By 1969, it was at 36%. Once the draft was eliminated however, the number fell down to 27%. The rate of graduates also began to rise to the extent that it is speculated whether college professors were grading papers easier in order to prevent students from dropping out.

Of course, since 80% of those fighting in the war were working class, college was an exit strategy that they could not afford. This is perhaps why Herr, as a middle-class boy stood out, and ended up an object of much fascination among the grunts. He had chosen to go to Vietnam, this concept showed him to be as insane as those who were losing their minds in the line of fire. Yet his madness was rooted in the same delusions, which attracted other young men into signing up for the Marines prior to the draft.

Herr had an obsession with entertainment media. How it portrayed war both seduced and desensitized him, as it did to many other men in the same environment. The signs of this he spotted in the language of the grunt and reporter. Rare was it that he heard a combatant harping on about American Freedom. They did not directly refer to any ideologies. Instead, their lexicon was based on its spawn; big budget movies, television shows, places built upon a “dumb fantasy”, places where heroes and villains actually existed.

It was, as he said himself, a “life-as-movie, war-as-(war) movie”. Marinated in cinematic

references, his descriptions speak for themselves in those regards. Fort Apache was “the lowest John Wayne wet dream”. Saigon was “the final reel of On the Beach”, and fellow correspondent, Sean Flynn was not merely a reporter; he was the son of the actor Errol Flynn, aka Captain Blood.

Whether a reporter or a soldier, many of those in his surroundings strove to escape the war by creating a fetish, coping with the horror by imagining themselves as heroes on a film reel. Perhaps the finest example he used to demonstrate this complex was when he quoted an injured marine howling, “I hate this movie”.

“You don’t know what a media freak is”, Herr wrote, “until you’ve seen the way a few of these grunts would run around during a fight when they knew there was a television crew nearby; they were actually making war movies in their head.”

“Most combat troops stopped thinking of the war as an adventure after their first few firefights, but there were always the ones who couldn’t let that go, these few who were up there doing numbers for the cameras. A lot of correspondents weren’t much better. We’d all seen too many movies, stayed too long in Television city, media glut had made certain connections difficult.”

Later, Kubrick, Herr and Hasford illustrated this fetish during Full Metal Jacket‘s raucous Battle of Hue scene.

[iframe id=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/cV9TClQu4Nk”]

As a camera crew awkwardly shuffles sideways through the American line, filming B-roll footage, they pass a platoon, consisting of the film’s main cast. The men, though engaged in a tense shoot-out with the NVA, take a few seconds each to revel in the presence of the camera. Joking like kids, they each offer a brief quip, well-timed and snappy enough to suggest they have rehearsed this scene on a regular basis:

Joker

Is that you, John Wayne? Is this me?

Cowboy

Hey, start the cameras. This is Vietnam: The Movie.

Eightball

Yeah, Joker can be John Wayne. I’ll be a horse.

Donlon

T.H.E. Rock can be a rock.

T.H.E. Rock

I’ll be Ann-Margaret.

Doc Jay

Animal Mother can be a rabid buffalo.

Crazy Earl

I’ll be General Custer.

Rafterman

Well, who’ll be the Indians?

Animal Mother

Hey, we’ll let the gooks play the Indians.

That question “Is that you, John Wayne? Is this me?” is a recurring line in the film, as is John Wayne a recurring name in Herr’s writing. Elevated to the status of demi-God, he is the noun used when one talks about American values.

The star of all the Cowboys and Indians flicks, in which “nobody dies”, his mannerisms served as something of a template for their behavior anytime a camera rolling. When grunts were showboating to get a few seconds on the evening news, they were not simply showing off, they were John Wayne-ing it.

Herr honed in on this influence, because, whenever the name crops up in conversation, the impression one has is that Wayne was a war hero himself. Easy it is to forget however, that in reality, the Duke only served his country in Reunion in France (1942), They Were Expendable (1945), Sands of Iwo Jima (1949) and eventually, The Green Berets (1968).

Yet, while the Duke could con viewers during the 1940’s, it was a different story as 1968 rolled into town. The Green Berets was in effect, a moment of clarity for many cinema-goers. This film, set in Vietnam, sparked major controversy on the day of its release (4th of July, naturally). Directed by, and starring Wayne, the plot can be summed up in two short sentences: An anti-war correspondent hates American foreign policy. John Wayne, aka Colonel Mike Kirby shows this pilgrim why he’s wrong.

Shot in 1967, The Green Berets was Wayne’s pro-American vision of South Vietnam, though Herr says it is more a reflection on life in Santa Monica. Not yet released when the Tet Offensive was launched, whether such a factor might have affected the overall tone of Wayne’s film is questionable. Still, the growing anti-War Movement refused to hold back on the man. Famously, Roger Ebert gave Wayne’s effort a fierce thumbs down, before going as far as to call him an irresponsible filmmaker:

“The Green Berets simply will not do as a film about the war in Vietnam. It is offensive not only to those who oppose American policy but even to those who support it. At this moment in our history, locked in the longest most controversial wars we have ever fought, what we certainly do not need is a movie depicting Vietnam in terms of Cowboys and Indians. That is cruel and dishonest and unworthy of the thousands who have died there… It is not a simple war… Perhaps we could have believed this film in 1962 or 1963, when most of us didn’t care much what was happening in Vietnam. But we cannot believe it today. Not after television has brought the reality of war to us… Not after 23,000 Americans have been killed.”

141 minutes of pseudo-patriotic arguments, The Green Berets was an almost literal lecturing of Herr’s ilk by Wayne himself. Dispatches though found a myriad of ways to illustrate the hypocrisy of Wayne, his patriotism and supposed intentions of honoring the men fighting in Vietnam by simply not acknowledging what was actually going on. He was playing Marines and VC’s. The grunts were playing cowboys and Indian. The image is as daft, as it is horrendous, but regardless, it is indicative of the blurred lines of reality Herr saw during those years. At its core, this is a book about one nation’s perpetual struggle to distinguish between dreams and reality. Those who were never in Vietnam often acted as if they were on the frontlines. Those who were fighting in Vietnam thought otherwise, imagining themselves as immortal characters printed on celluloid.

John Wayne was in Vietnam, even if he wasn’t. So too were the US grunts and Michael Herr. They were there, even if they thought they weren’t. Joan Didion, as she went down Haight-Ashbury to document the counterculture in Slouching Towards Bethlehem, comparing the hippy scene to a model-scale version of Vietnam, she thought she was there too. Country Joe, Francis Ford Coppola, the late-Michael Cimino, Connie Schultz, they were all there, even if they weren’t. “Vietnam, Vietnam, Vietnam”, Herr said in his sign off, “we’ve all been there.”