“This is a place of amusement, not a chamber of horrors”: The Enduring Legacy of The Battle of the Somme (1916)

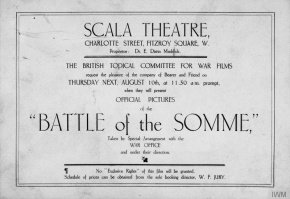

On the 10th of August 1916, a new film premiered in London’s Scala Theatre. This in itself was not unusual. Even during war time, the entertainment industry remained active. What was unusual was that this film marked the first time a recording made in a war zone was shown to the public before the battle in question had come to an end. The Battle of the Somme documentary and propaganda film would prove to be one of the most controversial, shocking and realistic depictions of the war that the British public had ever seen.

[pullquote]By January 1916, conscription had become necessary, and as the war continued, the roll of propaganda became increasingly important to act as a counterpoint to the lists of dead and damaged soldiers returning home from the front.[/pullquote] The war was supposed to have been over by Christmas 1914. As it dragged on, the patriotic fervour that marked the first months receded. By this point there was little left of the marching bands making their way through town and city streets to a chorus of cheers; men standing tall in their bright, and as yet unbloodied, uniforms. The attempt to portray the war as an old fashioned ‘all boys adventure’ had had some early success thanks to peer pressure and propaganda posters. Perhaps the most famous being the Lord Kitchener poster stating boldly: “Your Country Needs You”.

Many of the posters from the early months of the war also attempted to appeal to ideas of masculinity with slogans such as: “Daddy, what did you do in the Great War?” and “Women of Britain Say ‘Go!’”. In Dublin, recruitment officers went house to house with money in their hands to encourage the poor to sign up. However, by January 1916, conscription had become necessary. At first it was for single men, and shortly after for married men aged 18 – 41. As the war continued, the roll of propaganda became increasingly important to act as a counterpoint to the lists of dead and damaged soldiers returning home from the front.

This year sees the centenary of the Battle of the Somme – the largest battle of the First World War. Its name resonates down the years, symbolizing the futility of war; the thousands ordered to walk to their deaths in No Man’s Land. The battle began at dawn on the 1st of July and crawled to its end on the 18th of November. Before the Allies went over the top, there had been a sustained bombardment of German lines intended to destroy the barbed wire and enemy defenses, clearing the path for the advance. This attempt failed. The German trenches were barely touched by the shells and the barbed wire remained intact. In the end, all the bombardment had done was to alert the Germans to an oncoming attack, giving them time to prepare. Not expecting any opposition, the order to go over the top was issued. This resulted in one of the bloodiest battles continental Europe had ever seen.

Although the total number of Irish dead is still uncertain, nearly 2,000 soldiers were killed from Northern Ireland in the first few hours of fighting. At the end of the battle, there were around 420,000 British casualties. (This number includes the Irish dead and injured.) Ultimately, over a million men were killed or wounded. On the first day of the attack alone, there were 5,500 casualties from the 36th Ulster Division who were solely drawn from one community in Ulster. This goes some way to explaining how two civilian cinematographers found themselves and their equipment on the front lines. Filming a battle or war effort was still relatively unusual at this time. The film was created by two commercial cameramen, Geoffrey Malins and John MacDowell, under military supervision. In 1915, the British Government had sold the film rights to the war on the Western Front to a small group of commercial news film companies. The film was not produced by the government or the military but it was approved by them. This has led to some questioning of the bias and trustworthiness of the edited footage.[pullquote] Newspapers reported how some fled cinemas screaming at the sight of the dead.[/pullquote]

Filming began in late June and continued to the 10th of July, taking in the brutal first day that saw 19,000 British soldiers die. Malins detailed his experiences in a fascinating book called How I Filmed the War (1919). The book encompasses his Christmas spent on the Front, multiple arrests, being reported dead, attempting to film under heavy shellfire, the difficult trench conditions and a collision with a rather obstructive mule.

The silent black and white film is overlaid with a piano score as it captures the preparations being made for the upcoming attack. It includes soldiers marching to their positions, images of well-treated German prisoners, men preparing their weapons, religious services and long shots of No Man’s Land. Information panels hint at success when they inform the viewers that “high explosive shells fired by the 12-inch howitzers created havoc in the enemy’s lines”. The film also explicitly tries to tie the viewers back home, involved in the war effort, to the direct effect of their hard work. This can be seen from the information panel stating “along the entire front the munition ‘dumps’ are receiving vast supplies of shells: thanks to the British munitions workers”.

The preparations take up the first 30 minutes of the 75 minute film. After this, the action moves onto the battle itself. One of the earliest images is particularly famous: the soldiers all rushing over the top except for one man who seems to stumble; then the audience realizes that he is dead, face down in the mud. Other men struggle to make it through their own barbed wire and some indeed are shot down. There’s footage of men sitting by the side of a road, armed with bayonets and grinning at the camera. A mere 20 minutes after this section was filmed, they came under heavy machine gun fire. The bravery of the soldiers is shown alongside the wounded on stretchers.[pullquote] It is strange to think that the men who lived, worked and died in the trenches, who would climb over the sandbags into No Man’s Land, would also be requested at some point to act out the process that would shortly leave many of them dead.[/pullquote] At about 55 minutes in, the camera takes in the dead bodies that litter the Somme. It is important to note that some of the footage was staged, including one of the key scenes depicting men going over the top. This was controversial and damaged the filmmakers claims of realism. Also, there is little actual combat footage. It is strange to think that the men who lived, worked and died in the trenches, and who would climb over the sandbags into No Man’s Land, would also be requested at some point to act out the process that would shortly leave many of them dead.

The film premiered in London on the 10th of August 1916 before its general release on the 21st of August. Why was it shown before victory had been sealed? There is no definite reason for this. It is very possible that this was done to try and counteract the tide of negative information making its way across the channel. However tightly controlled the media had been, they could not stop news of the huge numbers of casualties from making its way home. Presumably, as the authorities had not expected any opposition, they might have hoped that the battle would be swift and victorious.

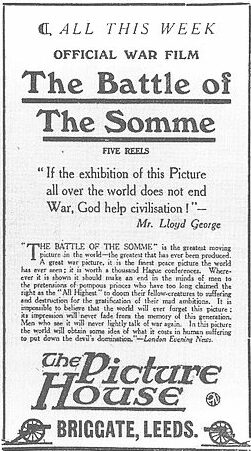

Within the first six weeks of its general release, The Battle of the Somme had been shown in around 2,000 British cinemas reaching a probable audience of 20 million people (i.e. half the population of Britain). It is one of the most attended films of all time. King George V is reported to have said, “The public should see these pictures that they may have some idea of what the army is doing and what it means”. It seems even by this point there was a general weariness to the bombardment of propaganda and the film may have been designed to try to counteract this. This is reflected in the headline chosen for The Manchester Guardian front page: ‘The Real Thing At Last!’, as the realism shown in the film proved deeply shocking, if not traumatic, for many. Newspapers reported how some fled cinemas screaming at the sight of the dead. One London cinema placed a sign outside stating: ‘We are not showing The Battle of the Somme. This is a place of amusement, not a chamber of horrors’.

[youtube id=”3lTnK5LAoBc”]

Ground breaking during its day, The Battle of the Somme remains as a remarkable work, having gone on to influence generations of documentary filmmakers and journalists. It marked a movement towards a more involved, visual form of war reportage, with journalists and cinematographers risking their lives alongside soldiers in battle in order to capture the events for posterity. The considerable viewership numbers also suggest a thirst to better understand the realities of war from those left behind, and foreshadows the future use and form of mass media propaganda. Even after 100 years, the film is still at times difficult, upsetting and shocking, taking the viewer as close as it is possible to be to the realities of life and war on the Western Front.