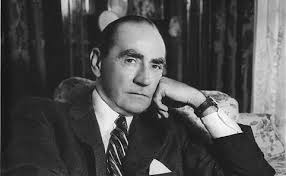

John Norton, Sydney Press Baron

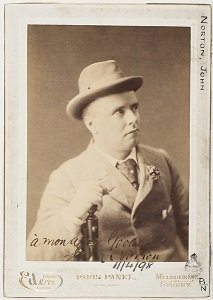

John Norton was born in Brighton in January 1858. His father was a stonemason who died before John was born, and his mother Mary remarried when he was a child to a silk weaver named Benjamin Herring. Herring was religious – the bad kind of religious. He administered beatings to John for his sins both real and imagined, as well as locking him up in isolation to think about what he had done. John was sent away to boarding school and may well have taken the opportunity to run away from home, though only his own inconsistent accounts of his childhood would substantiate that. His obituary claims that he went to college in France (he was a fluent French speaker in later life), dropped out to go to sea, then decided that shipboard life was not for him and left the crew when the ship was in Canada, spending some time there working in a lumber mill. (This does seem somewhat unlikely, and it should be noted that John loved to make up stories of his exploits as a young man.) He worked in 1878 for Edward James Reed, Chief Constructor of the Royal Navy, who was writing an account of his time in Japan and needed an assistant. After this he traveled around Europe, became fluent in French (if he hadn’t been before) and went to Istanbul on a walking tour. There he wound up writing for, and eventually becoming sub-editor of, the Levant Herald, a paper which was owned by a Maltese immigrant named Lewis Mizzi. John made a decent amount of money working on the paper, enough that when he came back to London he was able to take a sabbatical to become involved in politics. Then, by his own account, he discovered that some of his friends were planning to emigrate to Australia and decided on impulse to join them. In April 1884 he arrived in Sydney, Australia – a short man with a bullet-shaped head, determined to make his mark.

John’s international experience and forceful personality served him well in Sydney, and he soon became the chief reporter on The Evening News. It wasn’t the most prestigious newspaper in the city, but its liberal politics matched up well enough with John’s own. He achieved some early fame by championing the case of a Norwegian sailor who was convicted of public indecency for having sex with a prostitute in a park. The man was sentenced to twenty lashes, something John used to launch a campaign against flogging as a punishment. This failed, but it did get him noticed. In 1885 he quit his position at the Evening News and went freelance, in order to be able to spend more time getting involved in politics directly. In 1886 he returned to Europe as the official delegate of the Trades and Labour Council of Sydney, in which role he attended international trade union conferences in Paris, London and Hull. He also visited Dublin, by the invitation of Charles Stewart Parnell. On his return to Australia John was lionised, though his role in the growing Australian Protectionist movement (who advocated the use of tariffs to restrict trade to Australia and so allow local industry to grow) was to be blighted by internal rivalries. He returned to work at the Evening News, and in 1889 for the first time he became editor of a newspaper – the Newcastle Morning Herald. As the name suggests this was published in Newcastle, a city a hundred miles northeast of Sydney. There he did extremely well, boosting the paper’s circulation and demonstrating his own energy and drive. [1] However his drinking and resulting erratic behaviour eventually led to him being dismissed, and he returned to Sydney. It was then that he first went to work for The Truth.

The Truth had been founded in 1890 by William Nicholas Willis, a Protectionist politician. Despite the name, it was little more than a gossip rag used by Willis to drive his own political agenda. The first editor was Adolphus Taylor, another politician. The early days of the paper were riven with controversy. They had published an article by the Reverend Keatinge (who was actually a conman named James Crouch) and when Keatinge called at Taylor’s house to receive payment he found that Taylor was out. At home however was a twelve year old maidservant, who Keatinge was in the middle of raping when Taylor came home. Fearful of scandal harming their careers and the paper’s circulation, Taylor and Willis attempted to suppress the story. Of course, when the matter did eventually go to the police the backlash over the suppression was enough to end Taylor’s political career. Taylor’s health was also failing due to syphilis (which would kill him within the decade), and John soon became assistant editor, then acting editor, then editor. He also managed to buy a stake in the paper, which wasn’t considered by many to be an actual viable business concern. However John realised that controversy was the key to selling papers, and he soon boosted circulation (and profits) through a series of scurrilous attacks on public figures. One of these sued him for libel, and the trial was such a boisterous and ill-mannered affair that the judge returned a win for the plaintiff with minimal damages – the traditional signal that though the plaintiff had been libelled, his reputation was worthless. John counted this as a win, and celebrated with a drunken binge that ended with him being arrested for firing a revolver into the air. It may have been this that led to him being fired from his position at The Truth.

Of course, firing a man from a paper he has part-ownership in does tend to lead to legal complications. The legal battle was protracted and messy, complicated by the other legal challenges The Truth was facing at the time. The battle also didn’t stay confined to the courts – a drunken John Norton and William Willis encountered each other in the streets at one point and proceeded to start a “cheap display of fisticuffs” that included Willis swinging his cane and striking a bystander (setting off a general brawl as various groups took sides) and Norton allegedly jumping on Willis and biting his ear. Norton and his sympathisers seem to have won the day, as he later proceeded to get so drunk that he walked through a plate glass window. It was one heck of a night.

While the battle dragged on John got back into politics, and even stood (unsuccessfully) for election. Meanwhile without him The Truth suffered – a foolish attempt to bring the paper upmarket failed miserably, and an attempt to bring Adolphus Taylor back as editor proved disastrous. Finally in 1896 Willis decided to swallow his pride and sold the remainder of the rights to the paper to John. It was a major victory for him, one which he celebrated by almost immediately winding up in court on charges of sedition. This was because of his staunch and long held anti-Royalist views. Twelve years earlier, writing for the Evening News, he described Queen Victoria’s son Leopold (who had just died at the time) as “nothing better than a mentally deficient and morally vicious young man”. This time it was the Queen herself who he turned his rhetoric on. On one occasion he described her as:

…the podgy figured, sulky faced little German woman whose ugly statue at the top of King Street sagaciously keeps one eye on the Mint while with the other she ogles the still uglier statue of Albert the Good…

It was a similar attack that landed him in court, but though his clear disregard for the monarchy was undeniable, he still managed to sway enough of the jury to his side that they were unable to reach a verdict and the charges were dropped. John used this victory to build himself a solid reputation as a champion of the people, and it was a key stepping stone on his road to success.

1896 was also the year that John met Ada McGrath, the twenty-five year old daughter of a pair of Irish immigrants. Like John she was a Unitarian and the pair met at a church service. Their courtship however was fair from chaste, and they apparently first made love under a bush in the park. John proposed marriage, though it wound up being delayed when Ada discovered she was pregnant. She had a son, who they named Ezra, and three weeks later they were married. It was not the happiest of marriages. John remained an alcoholic, and if the pair fought when he was drunk he would often get violent with her. On one notable occasion he brought home a fish he had bought at the market and presented it to her with a grand gesture. Offended by her recoiling from the stench, he slapped her with it. Young Ezra was caught in the centre of this – sometimes his father was incredibly affectionate, yet on one occasion while arguing with Ada he grabbed the infant Ezra and threatened to bash his brains out. This dichotomy was typified in 1898, when John stood for election once again. He held young Ezra up before the crowd and declared him the “new Australia”. This would be one of young Ezra’s first clear memories, but it was combined with the memory of seeing his father viciously beat his mother in the carriage on the way home when she wouldn’t let him the driver to stop at a tavern they passed. It was far from the last time he would see his father attack his mother, though Ada was not always a passive recipient of these attacks, occasionally giving as good as she got.

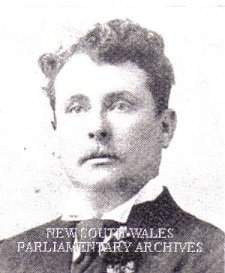

John won the election he used Ezra as a prop for, though that only lasted a month – he won the seat in a by-election in June, and lost it in the general election in July. Still, he would be a member of the New South Wales assembly for most of the next fifteen years. This was aided by the sudden reduction in competition for the role in 1901 – that was the year that the six Australian colonies became a single federated dominion. Most of the power (and the competent politicians) of the New South Wales assembly moved to the new federal government, which was temporarily housed in Melbourne until the new national capital of Canberra was created. As a result, the bar for membership of the state assembly was reduced – which may help to explain how a man who became as notorious for his conduct as John Norton was able to hang on to his seat. He also became notable for a different reason – he was widely credited with inventing the peculiarly Australian word “wowser”, in one of his typical denunciations on the floor of the house.

One of John’s most infamous run-ins in the Assembly was with fellow member Richard Meagher. Meagher had been a lawyer before he was a politician, and had defended a ferry master accused of trying to poison his wife. Though he had lost the case he had won on appeal, and the prestige from this had been the basis of his election. However Meagher had revealed to a fellow politician that he had tricked his client into admitting his guilt, and it was also later found that he had suppressed key evidence. The ferry master wound up jailed for perjury in 1895, and Meagher only just dodged a conviction for conspiracy. Three years later when Meagher was re-elected John Norton published a piece in The Truth referring to him as the “premier perjurer of our public life and the champion criminal of the continent”. Meagher attacked Norton in the street with a horsewhip in retaliation, and as he ran off Norton fired a revolver after him (and missed). Both men wound up in court, but John managed to avoid any fine on the grounds of extreme provocation. Even better from his point of view, in court he got to yell at Meagher:

You’re a beautiful bludger from a brothel!

Legal action became almost a third job for John at this time, as his fiery alcohol-fuelled temper and penchant for personal attacks in The Truth led to him constantly being sued for libel. On one occasion this went the other way – in 1902 Gilbert Smith, an ex-employee of The Truth, published a pamphlet when John was standing for parliament that describe him as “the most indecent person in the colony”, and said:

…after the breath of your body has sent a sirocco of blasphemy and filthy language through the House of Parliament…you actually asked the women in the constituency to pray to Almighty God to secure your return! Blasphemous wretch! The appeal of John Norton, seducer, violater, destroyer of home and family, guilt-laden, scrofulous-tongued filthily loathesome viper, asking good women to pray to the Architect of the Universe, Almighty God, to return such a wretch as you!

In the trial it was proved that Smith had been hired to write the pamphlet by one of John’s competitors in the election, but they could not agree on if it constituted libel or not. The case was dropped, but it had an odd coda that casts an interesting light on John. Apparently impressed by the quality of Smith’s writing, and not holding a grudge for what he now knew was work for hire, he gave Smith his job at The Truth back.

John’s personal life was as messy as his professional one. His quarrels with Ada continued, still violent and exacerbated by his alcoholism. Ada was almost certain that he cheated on her with prostitutes, while he was equally certain that she cheated on him with Nicholas Coxon, editor of The Sportsman. This was one of several new papers that John had founded – he was well on his way to being a genuine media mogul. In fact he had moved the house into a mansion on the outskirts of Sydney, which he decorated with memorabilia of his idol – Napoleon Bonaparte. Of course, once John became convinced Coxon was sleeping with his wife he fired him from the job, and Coxon responded by suing him for slander. It was during an argument over Coxon that John threatened to kill Ezra, while he was trying to get Ada to sign a statement supporting him in the court case. The court case itself was a complicated mess of accusations, retractions, twists (a former servant of the Nortons named Mary Byrne, who John had broken the nose of, was persuaded by Coxon to charge him with assault) and all the juicy gossip you could hope for. Naturally John was not going to ignore such a wonderful story just because he was in it – in fact The Truth gave blanket (and cheerfully biased) coverage to the whole thing. The matter just went on and on – the servant attacked Ada in a drunken rage outside court and managed to injure Ada’s mother, Ada wrote a blistering attack on Norton for having accused her of adultery and forced him to print it, and so on throughout 1902. By the end of it John and Ada were separated, but The Truth’s circulation was booming.

It was not the last major case that landed John in court, however. In 1906 as part of an extremely heated election campaign he was accused of murdering a man named George Grohn, a drinking buddy of his. At the time of the Smith trial John had accused Grohn of having leaked information to Smith about John’s previous career, and in the course of the argument John allegedly struck Grohn on the head with a beer bottle and killed him, then paid a corrupt doctor to issue a fraudulent death certificate. It was definitely agreed that he had died at John’s house, but John’s story (backed up by the undertaker) was that he had died of natural causes. Grohn’s body was exhumed and showed no damage to the skull or other injuries, leading the judge to declare that the lack of evidence (the sole witness for the prosecution being deemed unreliable) meant that the case had to be dismissed.

Eventually John and Ada reconciled, and settled down in “St Helena”, as he called his Napoleon-themed mansion. John’s drinking continued, and in one argument he fired a revolver into a door of the mansion. On another, he drove Ada and Ezra out of the house and they slept under the trees in the orchard. Ezra carried a burden as his father’s son – his infamy made him an outcast at school, bullied and ridiculed. Eventually a private tutor was hired, and he was taught at home. In 1906, around the time of the George Grohn trial, Ada became pregnant again. In 1907 she gave birth to a daughter named Joan. When she gave birth, she was still sporting a pair of black eyes her husband had given her in an argument a few weeks earlier. John did his best after Joan’s birth to improve his conduct, but Ada soon discovered that while she had been pregnant her maidservant Lizzie had also been concealing a pregnancy – one also caused by John. Worse was to come. An attack of bronchitis (exacerbated by drinking) led to John taking a trip to Europe for his health, and when he returned he had his sister’s daughter Eva Pannett in tow. Eva soon began accompanying Norton on his various business trips acting as his secretary, and Ada became convinced they were having an affair. She separated from John again, and took the children with her. John responded by attempting to kidnap their daughter Joan, who was still a child. This was the final straw, and Ada filed for divorce in 1915.

Ada almost immediately changed her petition to one for judicial separation, as she didn’t wish to give John the opportunity to marry Eva Pannett. Her petition was on the grounds of infidelity, with Eva and with a woman named Sarah Elizabeth Burgess who had stayed at St Helena. The latter was strongly supported by the evidence, the former much less so. Ada just seemed to be unable to resist trying to drag Eva’s named through the mud. John responded by cross-filing for divorce, alleging Ada’s infidelity with Nicholas Coxon and with a friend of hers named Harry Bird. John also wanted custody of Joan, but not of the 18 year old Ezra – perhaps understandable, as Ezra was a witness against him. This was on his mother’s other two grounds for separation – drunkenness and cruelty by her husband. It is from his and Ada’s evidence that much of our knowledge of John’s erratic private life comes. John’s case was undermined by evidence that his private detectives had tried to bribe Ada’s servant to testify to having seen her kissing Bird. In the end, the court ruled that John was guilty of drunkenness, cruelty and of infidelity with Sarah Burgess, but dismissed all the other charges (including that of infidelity with Eva). The Nortons, though still legally married, were over.

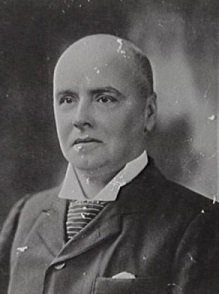

The court’s verdict on John and Eva’s lack of a relationship seems to have actually been borne out after the trial, as she was married the following year to one of his employees named Harold McClintock. [2] John, in the meantime, did his best to ensure that his wife and traitorous son would not profit from him. He gave St Helena as a gift to the government, and had a will drawn up making Joan his sole heir. Shortly after this his lifetime of heavy drinking finally caught up with him, and he died of kidney failure in a Melbourne hospital on the 9th April 1916 aged sixty-eight years old. His obituary did not mention his divorce, but did refer to him as the “Greatest Known Authority On Napoleon”. His funeral in Sidney drew a great crowd, as he had always been popular with the people. In all the focus on The Truth’s muckraking ways, it’s also worth noting that it did also do a great deal of good in exposing poor working conditions and campaigning for labour reform, and the working man had a great deal to be thankful to John Norton for.

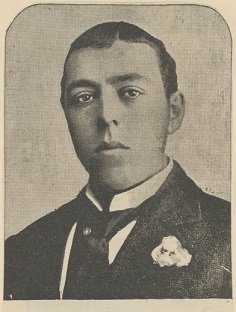

After John’s death Ada challenged his will, and managed to persuade the New South Wales assembly to pass a law making it illegal for a man to disinherit his family – a law which was conveniently backdated to apply to John. As a result Ezra, aged 23, gained control of The Truth in 1920. Ezra’s style was as abrasive as his father’s – one employee remarked that “I loathed every bit of my service with him” – but he was controlled enough to keep it in check in public. Ezra led The Truth to reasonable success, though he lacked his father’s bombast and willingness to commit to scandal. In the end he sold his newspapers off in 1953, aware that new privacy laws would undermine his core news strategy. He died in 1967, seven years after his mother Ada. [3] His mediocre career does seem to point to an unfortunate conclusion – John Norton was a profoundly damaged person, abusive and alcoholic. But it seems that in order to get the level of success he did, terrible was exactly what he needed to be.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] The Herald is still published to this day.

[2] Who, sadly for her, wound up convicted of embezzling funds to cover his gambling debts in 1919.

[3] And twenty years after Joan, who unfortunately inherited her father’s alcoholism but not his constitution.