Black immigration |The Lives and Travels of Thomas Awishee and John Jea

Thomas Awishee/ Osiat was born in the late seventeenth century, most likely in the Cape Coast, in what is present day Ghana. According to William Smith, surveyor for the Royal African Company in 1726, he was brought to Ireland as a child, where his master died. Smith records that he was entrusted to the care of a Widow Pennington in Cork, owner of a tavern – “the Crown or Faulcon” – who looked after his education and had him baptized by the Reverend Dr. Maule, subsequently Bishop of Cloyne. [pullquote] Jea settled in Limerick for over two years, preaching throughout Munster where he met considerable opposition from the Calvinists and the Roman Catholic clergy who “said they would have my life”.[/pullquote]

While I have been unable to confirm the details of Awishee’s baptism, there are records of a Mary Pennington, widow of Fernandino Pennington (d. 1704) – merchant and sheriff of Cork, who owned the FFaulkon (sic) on North Main Street.

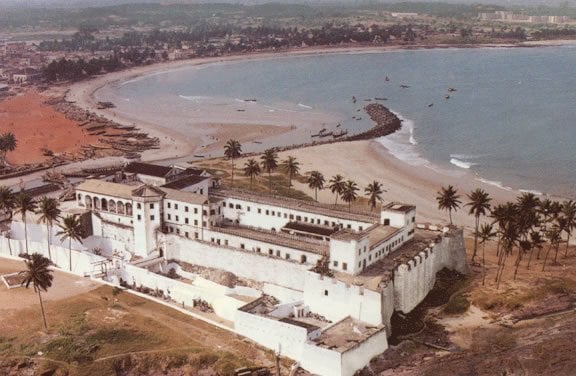

Thomas Awishee is interesting in that unlike the vast majority of Africans of that time, “having obtain’d his Freedom in this Manner” – through baptism presumably – he returned home to Cape Coast. At the time of his survey, William Smith noted that Awishee was living there in “great Grandeur”. Even more telling, he was “of the utmost service to the English.”

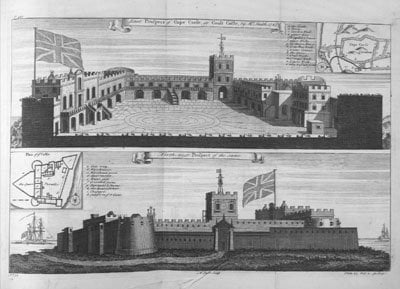

What exactly was he doing? Once again Smith gives some details. Awishee helped the English – meaning the Royal African Company (RAC), set up to exploit African commodities such and gold and slaves. Awishee was responsible for overseeing inland trade and preserving peace with the neighbouring powers including Dutch-held Elmina, a short distance from the fort of Cape Castle.

According to Royal African Company records, Awishee was originally employed by the RAC, in 1707, as a linguist, earning 6.75 oz of gold a year. He was one of their longest standing employees – some thirty five years – by which time his wages amounted to a considerable 18 oz of gold (£72) per annum.

Alicia Marie Bertrand’s work on the RAC, shows just how important men like Thomas Awishee were, in ensuring the smooth running of the slave trade. He “obtained great respect from European agents, and awards for his character and abilities as a trans-cultural broker.” His pay was on a par with his European counterparts. It seems that he was adept at managing the different factions in a diplomatic manner. However, Smith gives a different version of Awishee’s diplomacy when he engaged in a dispute with the nearby Dutch-held Elmina. His men “… took a great many prisoners, among whom were nine of the Petty Caboceroes of Elmina, whose Heads Tom Osiat (tho’ a Christian) caus’d to be cut off and sent them next day in a bag…”

After 1747, there is no further record of Thomas Awishee.

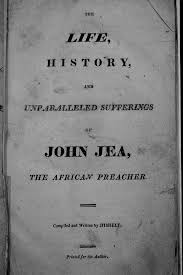

Like Awishee, John Jea was also removed from his homeland as a child, and sold into slavery. Unlike Awishee, who became part of the slave system, Jea became an international evangelical preacher and wrote an account of his life in 1822. He was born in Calabar, in Nigeria in 1773 and ended up in New York, where he was so badly treated, it was “almost too shocking to relate”. Following his conversion to Christianity, and his “miraculous” gift of literacy, he was made a freeman. against the wishes of his owners. He went on to preach throughout North America, before travelling to Britain, Europe and South America. Around 1802, he was in Ireland. He settled in Limerick for over two years, preaching throughout Munster. He met considerable opposition from the Calvinists and the Roman Catholic clergy who “said they would have my life”. In his book The Life History and Unparalleled Sufferings of John Jea, the African Preacher (1815), he reports having the support of the Mayor of Limerick and the commanding officer of the regiment.

I can find no contemporary evidence of Jea’s time in Ireland but local sources and newspapers in Limerick may contain some mention. Jea reports that he married “Mary Jea, a native of Ireland” before leaving the country. It was his third marriage and the details of his two previous attachments make for sad reading.

Like Awishee, John Jea disappeared from public record – around 1817 – after moving to Portsmouth and establishing a church there. His book was only rediscovered in 1983.

Series concluded

References and Further Reading

Bertrand, Alicia Marie. The Downfall of the Royal African Company on the Atlantic African Coast in the 1720s . (2011). Thesis. For an in-depth analysis of Awishee’s role in the Royal Africa Company: http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/thesescanada/vol2/002/MR81097.PDF

O’Sullivan, Paddy. The Dunworley Slave Ship: Amity 1701. http://lugnad.ie/amity-1701-the-dunworley-slave-ship/ This article provides a fascinating account of the shipwreck of Amity (of the Royal Africa Company) off the Cork coast in 1701. It includes an interesting theory by WA Hart, that the sole survivor, a black slave boy, could have been Thomas Awishee.

Smith, William. A New Voyage to Guinea. 1744. For an account of Thomas Osiat (Awishee), Caboceroe of Cape Coast.

Cape Castle Drawing: Image Reference: 2-605. Source: Based on William Smith, A New Voyage to Guinea (1744) in Thomas Astley (ed.), A New General Collection of Voyages and Travels (London, 1745-47), vol. 2, plate 65, facing p. 605. (Copy in Special Collections, University of Virginia Library) as shown on www.slaveryimages.org, compiled by Jerome Handler and Michael Tuite, and sponsored by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and the University of Virginia Library.