Still cooler than you: The Strokes’ Is This It at 15

In 1997 and 2000, Radiohead gave us back-to-back releases that would immeasurably change the direction of alternative rock. If the first, OK Computer, redefined the sound of the guitar-driven band, then the follow-up would completely dismantle it. Kid A didn’t just reinvent rock’s then-current soundscape, it tore down supporting structures and ripped out foundations in order to build something new. Furthermore, its alien aesthetics and divergent textures felt like the futuristic sound of the millennium we were being led into.

Almost overnight, Britpop and grunge album charters suddenly felt lost to the century they made their mark in. A year later, the New York Times would run a feature with a supporting image of an electric guitar as a gravestone. It appeared, for all intents and purposes, that the instrument was dead. Too bad that five well-to-do upstarts from NYC didn’t get the memo.

2001 was the year in which The Strokes burst onto the scene with the electrifying Is This It, one of the finest debuts of modern times. These guys didn’t break out the way you were ‘supposed’ to and yet their back-to-basics and undeniably infectious garage rock would come to define the early aughts. Their formation, for instance, isn’t exactly the stuff of rock ‘n’ roll folklore. Lead Singer Julian Casablancas and guitarist Albert Hammond Jr. originally found each other as 13-year-olds in a Swiss boarding school, a meet-cute that makes the Ivy League prep of Vampire Weekend look downright edgy by comparison.

The Strokes formed in 1997 and in ’98, Hammond would join the band that now consisted of Casblancas, fellow guitarist Nick Valensi, bassist Nikolai Fraiture and drummer Fabrizio Moretti. It was Hammond’s inclusion, however, that acted as a the catalytic event which allowed the band to find their sound, his blistering guitar lines giving The Strokes their ferocious core and ensuring they stood out in a city saturated with “New York” bands.

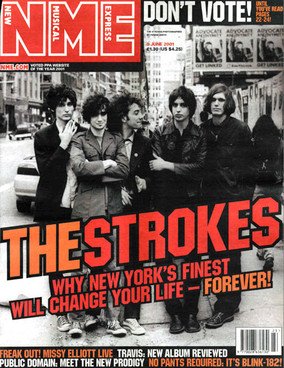

The emergence of The Strokes defied expectation because they did something that American rock bands had ceased doing a long time ago: not only did they think they were cool, they insisted upon it. And it was their mopped-topped, bed-headed leader who personified that cocky self-awareness. The previous decade brought the Cobains and the Yorkes to prominence, gloomy introverts who helmed their groups and felt uncertain about their lime-lit position, but Casablancas was no such reluctant frontman. Donning a bleach white suit jacket in those early years, he strutted about the stage like a rejected character from the Rock of Ages stage show, his signature, modified growl answering the question of what a chain-smoking Jim Morrison might sound like. The group’s energetic freneticism injected some much-needed youthful bravado in what seemed to be becoming an old man’s game again. Skinny-jeaned and half-blind with fringes, The Strokes cut a distinctive figure – they just looked like the kind of band would play an impromptu gig in the most popular kid’s living room. Even their apathy and disaffection shown over their whirlwind success just seemed to scream ‘cool’.

No surprise, the press lapped it up. The Strokes weren’t just good, they were the saviours of the genre, who bore the torch of “indie”, and would keep it burning brightly in the ensuing and as yet unfamiliar decade. Those awestruck early NME interviews read like they were written by Jay Baruchel’s Zeppelin-crazed stalker in Cameron Crowe’s Almost Famous. Perhaps the band were in on the joke, knowingly eager to be seen as the rebellious scamps who were only interested in the beating heart of rock and roll to the point of absurdity. Casblancas was frustrated with the reality of the recording process not allowing the band to just get it one take and get out: “It’s anti-image. I don’t want to be some brainiac band. I just want us to do what we do: ROCK YOUR FUCKING BALLS OFF.”

It’s true, they definitely weren’t the brainiac band, but that was their charm. Maybe we didn’t want to admit it, but perhaps a part of us felt a little alienated by the haughty esotericism of Kid A, and we needed to feel that something could in fact, “rock our balls off” once more. Is This It was that vital release, 36 magical minutes of unashamed, joyous and earth-rattling sonic assaults. As if by brute force, we were saved from the horrifying clutches of nu metal (an alternative universe exists without this album and with Fred Durst dominating the zeitgeist for many more depressing years).

With Is This It, The Strokes weren’t exactly embracing the new. Instead, they evoked the dynamic power of their city’s distant predecessors; the fiery punk stylings of the New York Dolls, the vocal chutzpa of Joey Ramone, the commercial antagonism of latter-day Velvet underground. The music wasn’t particularly fresh, but they made it feel like it was, like they were the first guys to think of moving from C to D. These songs were simple but effective; they just hit you right in the gut. There is a legitimate case that could be made for the album’s singles being the three finest all-out rock songs of the period. ‘Someday’ and ‘Last Nite’ remain scintillating pop perfection, ageless wonders that directionless millennials can find reassuring comfort in as reminders of a more hope-filled youth. Fraiture’s nimble solo bass line at the bridge of ‘Someday’ may sound a bit too much like The Jam, but it will – to this day – continue to induce nostalgic gazes and air-bass slapping solos in any club that plays the song.

[youtube id=”BXkm6h6uq0k”]

‘Hard To Explain’ is perhaps unjustly the least enduring of the three, standing out as both the album and the band’s finest moment. The ever so slightly incongruous, duelling guitars have often been a staple of the Strokes but here Hammond Jr’s and Valensi’s instruments coalesce seamlessly and symbiotically to create a piercing, homogenous whole that gives the track a fierce sense of acceleration. Casablancas’ speed run through the chorus is equally bewitching, with his “enough said” of an abrupt finish proving that some songs are so good that don’t need an outro. Really though, the rest of the record is filled with coulda been/ shoulda been singles. Is This It is that unique debut that plays through like a compact Greatest Hits disc. In hindsight, it very much almost is.

‘Alone Together’, ‘Barely Legal’, ‘Take It Or Leave It’; peerless college rock tunes enriched with contagious hooks and irresistible riffs. Album cuts they may be, but how many of those under-appreciated alternative rock groups of the day (The Dismemberment Plan, Enon) secretly wished they could drop just one of these so as to enjoy just an ounce of then mainstream airplay the Strokes were afforded. It’s strange that I often remember Is This It as thoroughly summer album, considering only one country—Australia—received the album when it first came out in July (a winter release down there). The US version would be delayed due to the September 11th attacks, eventually arriving without the iconic, risqué cover and minus the incendiary ‘New York City Cops’ – this was the uneasy period of the Clear Channel memorandum, after all.

Regardless of where it was listened to or what version was heard, Is This It seemed to make the same seismic splash wherever it landed. Its painfully earnest, “authentic “ post-punk revivalism reverberated around the world, its influence and long looming shadow present both at home and abroad in the guise of Interpol, Franz Ferdinand and Arctic Monkeys – all bands who, like The Strokes, arguably released debut albums of a quality that they could never quite match again. The dream didn’t last and ‘real’ rock’s time at the top again was always going to be brief. Still, Is This It is an unquestionable pillar of that era. The manner in which The Strokes released these songs, drip-feeding them throughout the year through EPs, singles and multiple album releases made them nigh-omnipresent in 2001. It felt like they were the only band that ever mattered, and for a fleeting moment, they really were.