Literature on Film | Part 8 | The Disappointing Legacy of Alan Moore’s Watchmen

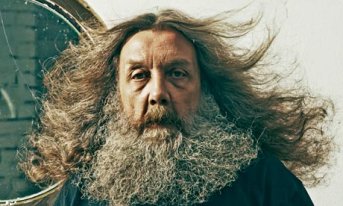

Born in Northhampton in 1953, and remaining there his entire life, Alan Moore’s creative run of form from the early 1980s is up there with the best of them. After being kicked out of school at the age of 16 for dealing LSD, Moore spent a number of years working odd jobs, experimenting further with drugs and seemingly absorbing the entire western canon. By his mid 20s he had a steady gig as a cartoonist for his local newspaper, drawing and writing the one page adventures of Maxwell the Magic Cat (he’s since commented he would have been very happy to spend his career just doing that). Gradually Moore found more cartoonist work with the NME, and eventually found steady work as a writer on a number of British science fiction anthologies, including the iconic 2000AD. Moore’s work on 2000AD got him noticed by DC comics, who soon started to offer him regular work. A comic book fan since his youth, Moore quickly developed a reputation for taking old and forgotten characters and blending them with his signature style of virtuoso storytelling, staggering intelligence and literate weirdness. His first regularly series for DC was Swamp Thing, an old 1940s character which he infused with a Cronenberg sense of body horror and used to explore issues like AIDS and feminism. He followed this with one off stories on most of the major DC characters, as well as his pet project, the socio-political epic V For Vendetta. In 1985 Charlton Comics, a smaller publisher, went bust and sold the rights to their characters to DC. Interested in working on a long story that featured traditional superheroes, Moore pitched DC a story featuring the Charlton characters. Liking the proposal, but fearing it would leave a lot of the characters they had just bought useless, DC urged Moore to refit the story with original characters. With aim of creating a “sort of superhero Moby Dick”. Moore agreed, and in 1986 the first of Watchmen’s 12 issues appeared.

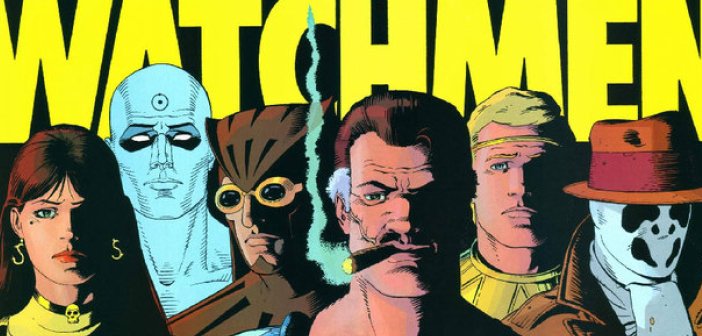

Beginning in an alternative 1985, Watchmen follows an underground superhero Rorschach, investigating the murder of the government sanctioned Comedian. In this world, super-heroism was a fad in 1930 and again in the late 60s before being outlawed in 1975. Convinced that a serial killer is targeting superheroes, Rorschach proceeds to visit his former colleagues, some of them washed up, some working for the government, to help him unravel what he’s convinced is a vast conspiracy. To reduce Watchmen to a plot summary, to narrow it down that much, is like saying that Joyce’s Ulysses is just about a man walking around Dublin or that Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow is just about scientists working on a bomb. It would almost take a series of articles to cover everything that Watchmen is “about”. Moore’s narrative spans decades and examines a vast number of themes, chief among them the role of the past in shaping the present, idealism vs. disillusionment, American imperialism in the latter half of the twentieth century, love, ethics, the nature of time and perhaps most fittingly what people are willing to do to attain power and what responsibilities they have once they have power. It’s chock full of allusions, cribbed from “high” and “low” culture (chapters titles are taken from quotes found in the works of Shelley, Jung, Einstein, Nietzsche, Blake and The Bible, as well as lyrics from Bob Dylan, Elvis Costello and John Cale. Bertolt Bretch and William S. Burroughs get a number of obvious nods throughout the series also) and symbolism, most of which only becomes apparent on a fourth of fifth reading. I first read it when I was about 14 and to this day I still find it a staggering piece of work, where something new is almost always revealed upon each re-reading. Because it’s a story told via images instead of prose, symbols, hints and allusions can be hidden in the background without interfering with moving the narrative forward, but because it’s read and not viewed (like a film) your not forced to move at somebody else’s pace. This allows Moore to plunge you into a fully formed, complex, world without ever being impenetrable. Moore had an innate understanding of the medium he was working in, and used tricks and techniques that where only capable within that medium. For this reason, Watchmen is a singular piece of work, which is why Zack Snyder’s 2009 film adaptation feels so shallow.

The only major plot change that Snyder made is a slight change to the ending. The twist revealed towards the end of Watchmen is the Adrian Veidt, an ex-superhero turned tycoon, has been orchestrating everything, in an effort to end the Cold War. In the comic Veidt genetically engineers a creature that resembles an alien squid and drops it into New York City, convincing the USSR and the USA that they need to put there differences aside in the face of an otherworldly threat. In the film, Veidt bombs NYC, using a weapon that mimics Dr. Manhattan’s otherworldly abilities, inspiring the USSR and the USA to unite against him. Snyder’s argument was that the squid was too unrealistic and that audiences wouldn’t go with it. That one decision alone demonstrates everything wrong with Snyder’s take on Watchmen.

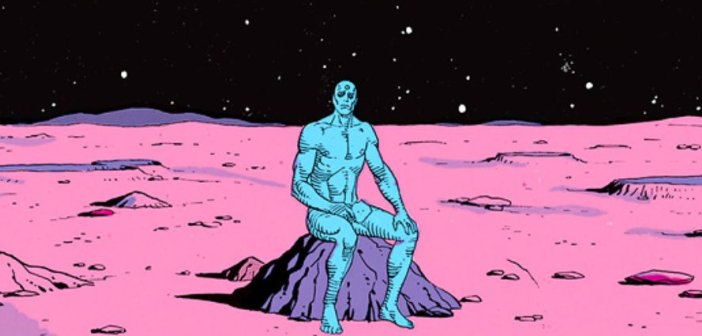

Moore’s only character with any super powers is Dr. Manhattan, effectively a physics textbook come to life. A physicist caught in a nuclear accident, Manhattan experiences time as all happening at once, and can see and control things on a sub atomic level. Moore’s depiction of him is that of a lonely god, so far removed from the rest of humanity he comments that he’s in no position to “condemn or condone” the actions of others. Elsewhere, Rorschach, Moore’s urban vigilante, is a smelly, far-right crackpot and Nite Owl, his technocratic crime fighter, far from being a suave playboy, is a bespectacled loser, a “flabby failure”, who can’t get it up.

Like all great works of art, Moore’s primary concern is, ultimately, with the human condition. He doesn’t bother explaining how a person could be transformed into a being of pure physics because, like trying to explain how batman pumps up his tires, to try and do so would be utterly idiotic. What sort of relationships, what political allegiance, what laws, what sort of morality would a god-like human believe in? How disturbed would somebody have to be to actually fight petty crime night after night? What type of sexual hang ups would they have? Moore trusts the reader to understand that these characters are unrealistic and larger than life, but it is this conceit that allows him to explore deeply philosophical ideas and themes, questions that people have asked since the beginning of time. Moore doesn’t answer these questions because they’re impossible to answer, but by placing his characters in operatic, almost biblical situations, he’s able to probe and explore them. It’s been argued whether or not The Comedian is the ultimate existentialist or an egotistical nihilist? Is Rorschach a Kantian or an Objectivist? Can or should an individual dehumanise themselves for a higher ideal, or is it even possible to truly shed individuality? It’s impossible to say who is right or wrong in Watchmen, because Moore doesn’t write any black or white characters. Indeed, the most demented characters in Watchmen, The Comedian and Rorschach, are the ones who view the world in terms of absolutes. Moore deliberately created characters that are hard to judge, because no matter how “unrealistic” these characters might be, he wanted them to reflect the reality of our day to day lives.

Snyder displayed a fundamental misunderstanding of Moore’s work when he was concerned about the realism of the ending, and this misunderstanding is reflected in the film’s overall aesthetic. Where Dave Gibbons drew Watchmen so that each image is warm and bright and clear, Snyder’s film, gauging from the poster alone, is gritty and grimy and full of obvious CGI. The major visual difference is that film is much more gratuitous. During fight scenes, we see bones burst through skin and bullets tear through skulls and during the sex scenes Snyder leaves nothing to the imagination. You get the sense that he didn’t have enough faith in the source material, and every time there’s a “realistic” or “gritty” action sequence it is as though he’s screaming at the audience that even though this is a superhero film, it’s a film for adults as well, which gives the entire film a very adolescent air.

At this time of writing (20th of March) Snyder’s Batman Vs. Superman is five days away from release, promising simultaneously to kick off a new film franchise for Warner Brothers and offer another “gritty”, “dark” and “realistic” take on the superhero story. For lapsed fans like myself the build-up to Batman Vs. Superman represents everything wrong with comic book films, the crass commercialism and the constant, teenage, reassurance that “grittiness” and “realism” are a benchmark of maturity and quality. This has been the unfortunate legacy of Watchmen, that once Moore showed that superheroes could be used to tell stories for grown-ups, a lot of creators became obsessed with justifying why they had to be used in stories for grown-ups. While there have been some comics in the same vein as Watchmen, like Neil Gaiman’s dark fantasy series Sandman, Jason Aaron’s crime drama Scalped or Art Spiegleman’s Maus, amongst others. The main reaction to Watchmen was how writers and artists who lacked Moore’s finesse attempted to capitalise on the success on Watchmen by trying to be “gritty” and “realistic”, resulting in what Moore described as “years of grim and pretentious stories”. Characters spoke in hard boiled platitudes not dissimilar to Rorschach and the more fantastical elements where toned down so that stories could attempt to tackle social issues, a tricky path to go down. It’s all well and good to want to examine urban crime in, say, a Batman story, but that can very easily turn into a wealthy white man beating up poor people. It’s worth noting perhaps that the term Superman is a literal translation of Ubermensch, a phrase Friedrich Nietzsche used to describe the ultimate man, a term that fascist philosophers would later pick up on. Moore has dismissed the stories that have imitated him as little more than ill thought out, neo-fascist posturing, something that could be said about Zack Snyder’s filmography as a whole (see 300). Certainly, in Watchmen he can’t help but make Rorschach the films tragic hero, a fact that would likely disturb Moore, where he to ever watch the film, who always claimed to be surprised when people tell him the ultra conservative character is their favourite in the book. Moore fell out with DC shortly after finishing Watchmen and has largely avoided mainstream comics since then, and while he does occasionally return to superheroes, it’s always been to embrace the silliness and the absurdity of the genre.

In spite of his flaws as a film-maker, it is genuinely difficult to actually condemn Zack Snyder for making a poor Watchmen film. The main issue is ultimately the struggle to get so many ideas into a film, even if it is a very long film. This is largely why Daredevil and Jessica Jones have been able to tell “mature” stories on Netflix, because they have time. 11 episodes is a lot of time to introduce and flesh out ideas, instead of just hurling them at an audience (Terry Gilliam, who adapted another famously un-cinematic work, was attached to Watchmen for years, but left the project with the advice that it should be done as a television series). Ultimately time makes all the difference between something being well thought out and being empty grand-standing. It’s unclear how long this bubble of “gritty” superhero films will last, but in examining its origins in Moore’s Watchmen a phrase comes to mind that’s so clichéd it’ll probably show up in one; that it’s a road paved with the best intentions.

Featured Image Credit