Oscar Watch | Why Room Should Win Best Picture

(Spoilers for Room and The Revenant)

If the only thing you know about Room was the premise, it would be very easy to imagine a different film, perhaps a version that would play in the much coveted 2am slot on the Horror Channel between a government experiment on ants gone wrong and a slasher film with at least one former Dawson’s Creek cast member. Our heroine, Joy, is trapped in a grotty cell by a charismatic monster and is forced to play by his elaborate rules to survive. There would be a graphic rape scene (the director reasoning that it would be “dishonest” to not confront the viewer with the crime in all its lurid details). These tortuous events would continue until she realised she was pregnant. Now finding new strength, she devises a cunning plan for escape and extracts a cathartic revenge from her captor. The film ends with her triumphant freedom. It was unpleasant but the monster was vanquished.

Of course, we didn’t get this film, but we have plenty of stories like that, treating rape and sexual abuse as a plot device to signal to the audience that you are watching a gritty film for adults. Horror films, crime dramas, even the odd superhero film have all fallen prey to this lazy trope. Room is different as it takes a potential queasy idea and makes a sensitive, thoughtful film that explores the challenges of surviving and crucially what happens after, for the victims, both direct and indirect.

Room takes what would be standard thriller tropes and discards them throughout. The escape is in the first act and though the plan is a good one, it’s not played to full Hitchcockian suspense. We never get any closure on the final fate of Old Nick, their captor. In fact, he disappears from the film entirely about midway. Instead the film focuses about Joy’s attempts to protect herself and her son both in their physical prison and the mental one that follows them outside of Room.

Told from the perspective of Jack, the film trusts the audience to imagine for themselves the horrors of that converted shed that makes up his entire world. Lenny Abrahamson’s use of subjective camera perfectly contains Jack’s viewpoint, showing the beauty he has found in a barren place but also containing the hints at the distance between his reality and his mother’s. Potentially exploitive scenes are played with just the right amount of information, impressing us with the horror, without entering into voyeuristic detail.

The script (adapted by Emma Donoghue from her acclaimed novel of the same name) has a strong handle on dialogue and keeping Jack’s perspective real. In fact, it may be one of the rare films that improves on the book, as it overcomes the novel’s chief weakness of trying to comment on wider themes of celebrity and victim blaming while remaining plausibly within the viewpoint of a naive 5 year old with no world experience.

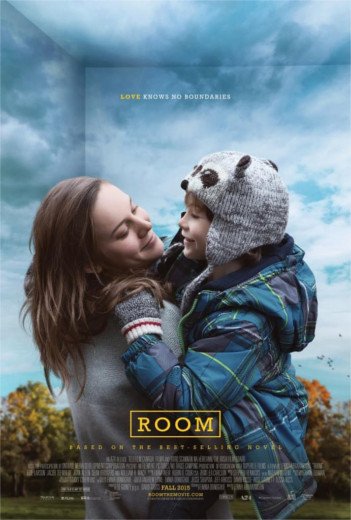

Much has been written about the acting, but it’s worth emphasising Jacob Tremblay’s faultless performance as Jack. Additionally Brie Larson, who is nominated for Best Actress and deservedly favourite to win, gives a beautifully humane portrayal of a woman who wants to live but is trapped in a mode of surviving. It’s a tough, tender performance that captures in an expression the horrors that Jack (and the audience) have been protected from. The cast is rounded out with welcome roles for Joan Allen and William H. Macy, but, really, the film is about a mother and son relationship that we both care about and fear for its safety.

For this filmgoer, it’s exciting to see one of Ireland’s most exciting filmmakers, Lenny Abrahamson further develop his voice and find more variations on his pet theme of people trapped in metaphorical (and in this case literal) cages. Frank explored mental illness, What Richard Did looked at guilt and this outing captures depression and its terrible wrath. It’s a real tearjerker of a movie, but it catches you in unexpected moments. An offhand comment, a certain shot of the light, little reminders of what Old Nick stole from them but also what he can’t anymore. A film of such emotional honesty is rare and turns what could have been a story of oppressive despair into one of hope and thoughtfulness. You don’t know what will happen to them but you know they have a chance.

My hypothetic version of Room may have seemed the height of offensive hackwork, never destined to get any further than an average episode of Law & Order, but this reductive view of abuse permeates through all levels of storytelling. To give a recent example, we just need to look at another Best Picture nominee and a highly tipped one at that. The Revenant is about a man called Hugh Glass surviving a bear attack on the frontier and seeking revenge on the men who left him behind. It’s a compelling true story but the film makes the addition of Powaqa, a kidnapped daughter of the Arikara, a local Native American tribe. She is raped once onscreen (and implied offscreen multiple times). This doesn’t add anything of note to the picture other than villains to dispatch of and add a further veneer of rottenness in the film’s world. In the end, it serves more to inform us more about Hugh Glass than highlight the real (and still current) sexual violence against indigenous people.

If nothing else, Room should win Best Picture as it’s time to stop rewarding the use of sexual violence as a plot device and its treatment as a piece of fiction.