Natalie Clifford Barney, Queen of the Paris Lesbians

Natalie Clifford Barney was born in 1876 in Dayton, Ohio. Dayton is a city that has produced more than its share of pioneers – the Wright brothers, Charles Kettering and many others. Natalie wasn’t an inventor but in her own way she was a pioneer, blazing a trail that helped set the course for Western society in the 20th century. And all she had to do was be honest with the world, about who she really was.

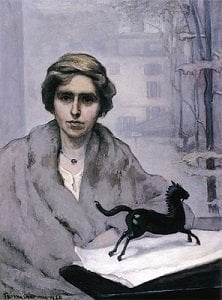

Her father Albert was rich, having inherited a fortune from his railway pioneer father. He was also an alcoholic, and tried (but failed) to dominate the women in his life. The main such woman was, of course, Natalie’s mother Alice. Alice had been engaged to another man, the explorer Henry Morton Stanley, but while he was off in Africa she met and married Albert. Her parents (her father was a Jewish immigrant, which would become a factor in Natalie’s life much later) encouraged the match, as they had found Stanley unsuitable. Alice had been an artist in England, but her husband discouraged her from continuing her career after their marriage. In 1882, when Alice was in New York with her children, the five year old Natalie ran past Oscar Wilde while trying to escape a group of young bullies. The highly amused Oscar scooped her up and shooed the bullies off, then sat her on his knee and told her a story. Natalie later recalled this as her first Great Adventure. When Alice came to find her, she and Oscar also hit it off and they agreed to go out to Long Beach together the next day. Oscar advised Alice to take her art more seriously, and she took his advice to heart. She went on to take classes in painting from Whistler and Carolus-Duran, becoming possibly the most famous female American artist of the 19th century.

It may have been this artistic bent that led Alice to send Laura and Natalie to school in Paris five years later. She accompanied the 8 and 10 year old sisters on the trip, and though they were staying at a boarding school she took an apartment to be near them (and, of course, to study in the great city). Natalie fell in love with Paris, and learned to speak French like a native. It was also at this time, aged 12, that she realised she was a lesbian. Her first relationship with a woman came after her mother had moved the family back to America, and began as a summer fling. In 1893, during a vacation in Maine, the seventeen year old Natalie met a nineteen year old girl with green eyes and red hair that reached to her ankles. Her name was Eva Palmer, and like Natalie she liked horse-riding, poetry, and other women. The two began a romance that, like a lot of Natalie’s romances, would eventually turn into a long friendship. [1] Natalie seemed to have a knack for managing to remain friends with her ex-lovers, which given her rejection of monogamy was fortunate for her.

Alice returned to Paris in 1896, looking for treatment for her daughter Laura. She had injured her leg as a child, and still suffered chronic pain. Natalie came to Paris with them, but set up her own household – first with Eva, and then on her own. From this point on Paris became, except for a few interludes, her permanent home. In 1899 she became well known in Paris when she had a brief affair with the famous courtesan, Liane de Pougy. Liane (who had been born Anne Marie Chassaigne) was an occasional chorus girl who had become the premier demimondaine of Paris. Natalie saw her at a dancehall, and decided to try to seduce her. To that end she dressed in a pageboy’s uniform and turned up on Liane’s doorstep, proclaiming herself a messenger of love sent by Sappho. Liane was charmed by her directness, and the two had a brief but passionate affair. They eventually split up because Natalie strongly disapproved of Liane’s sex work and sought to “rescue” her. Liane was as comfortable with her prostitution as Natalie was with her lesbianism, and had no intention of being rescued. They separated, but did remain friends. Liane went on to write a fictionalised account of their relationship, Idylle Saphique, which became a best seller. All of Parisien society, of course, knew Natalie was the model for “Flossie”, the main character’s female lover. Natalie wrote her own account of the affair, but failed to find a publisher. Though her book was by her own account not the best, it’s notable for her uncompromising acceptance of her own sexuality – a rarity at the time, and something that made her an icon for other lesbians.

My queerness is not a vice, is not deliberate, and harms no one.

1899 was also the year her mother began hosting a salon in Paris. Salons had originated in Renaissance Italy, but it was in Paris that they became an institution. A salon was basically a gathering of artists and art enthusiasts, with art defined broadly to cover painting, poetry, literature and music. People would meet to exchange ideas and discuss each other’s work. Young artists could find mentors or help, older artists could pass on their skills and in return be respected for their accomplishments. The core of each salon was the salonnière – the host (almost always female) who invited the guests and helped to ensure a collaborative atmosphere. Salons were originally the province of the aristocrats, an extension of the Renaissance pattern of patronage. By the 19th century however salons had become a far more democratic affair. Alice Barney’s salon was artistically focused – painters she admired, painters she had learned from and their friends. It was never a major part of the Paris scene. But by demonstrating to Natalie the mechanics of the salon, it would have an immense influence.

Around the turn of the century Natalie met Renée Vivien, a symbolist poet. She was, despite her name, actually British (though she had an American mother). She had been born Pauline Tarn, but on her father’s death in 1898 she had inherited his fortune and used it to move to Paris. At the time it was one of the few places on Earth where you could live as an “out” lesbian without suffering persecution. The two women began a relationship, though one doomed from the start by Renée’s self-destructive tendencies and Natalie’s inability to commit to a monogamous relationship. Natalie was throughout her life both incapable of remaining faithful to a single partner, and incapable of understanding why she should, or why they would want her to. In 1901 Renée left Natalie. Natalie was heartbroken, and unable to accept the relationship was over. She spent years trying to win back Renée unsuccessfully.

In 1900 Natalie had her first book published, a collection of poems titled Quelques Portraits-Sonnets de Femmes. Her mother illustrated the book, reportedly unaware of the lesbian subtext. A newspaper in Washington caught wind of this, and led a gossip column with the headline:

Sappho Sings in Washington!

Alfred read this and was horrified. He had always been scandalised by his wife’s artistic tendencies, but this was a step too far. He travelled to Paris, and bought up all the copies of the book he could find to destroy them. This was just one of several indignities Alfred suffered – the same year Laura converted to the Baha’i faith (Alice would also later convert). The stress seems to have shortened his life, as he died in 1902. Natalie had been forced to use a pseudonym, Tryphé, [2] for her writings before this but Alfred’s death left her financially independent. It would be forty years before circumstances would force her to compromise again.

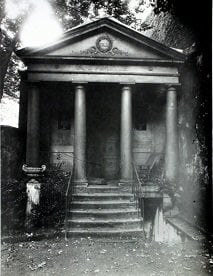

With her new personal wealth, Natalie began conducting a salon of her own. The focus was (naturally) on female artists and performers – Mata Hari was one of those who entertained Natalie’s guests with risque performances. [3] Originally these took place at the house in Neuilly she had shared with Eva. After Natalie’s plan for an outdoor performance of her play Equivoque (about the death of Sappho) was blocked by her landlord, she cancelled her lease and moved out. She relocated to a small detached house in the Rue de Jacob, with a large private garden that included a Greek-style temple. Here was where Natalie would host her salons every Friday for many decades to come. Her guests did not just include her fellow lesbians (though the salon became a focal point for them), but also early feminist writers like Gertrude Stein and Colette, and even male poets and writers like Ezra Pound (a close friend of Natalie’s), TS Eliot, F Scott Fitgerald and, on one occasion, Marcel Proust. Later, in the 1940s, when Truman Capote visited Natalie she was able to introduce him to the people who had served as models for the characters in Proust’s masterwork, À la recherche du temps perdu.

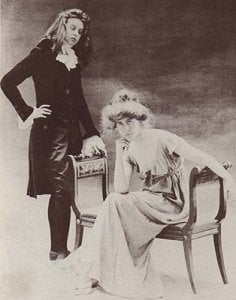

Though World War I brought an end to the Belle Époque, the golden age of Parisian culture, Natalie’s salon endured. During the war it was a centre of pacifist action against the war – a risky business that would normally have led to considerable unpopularity. Perhaps Natalie’s position on the fringes of society shielded her from this. In fact, this attitude helped to enhance the position of her salon and may have led to its longevity after the war. The uncompromising stance gained Natalie a cachet in the artistic community that those who converted their salons into wartime hospitals lacked. It was during the war that Natalie began her relationship with Romaine Brooks, an American painter who was one of the few long-term lovers in Natalie’s life. She was willing to make theirs an open relationship, and as a result the two remained involved for over fifty years. Another long-term relationship was with Élisabeth de Gramont, an aristocrat descended from King Henri IV who was known as the “Red Duchess” for her outspoken socialist views.

By the 1920s the “Fridays” at Natalie’s salon had become a Paris institution, and a centre for socially progressive thought. This was epitomised in 1927 when, in response to the Académie Française’s refusal to admit women to their ruling council of “immortals” (who were the official literary authority in France), Natalie established her own “Women’s Academy”. This was not really a body, but rather Natalie’s way of honouring the women that she felt the French literary establishment ignored. Honorees included feminist writers like Collette and Gertrude Stein, and writers who wrote on lesbian themes (like Lucie Delarue-Mardrus or Renée Vivien, who had died a few years earlier without ever reconciling with Natalie). Others included Djuna Barnes (a bisexual American journalist turned writer), Mina Loy (a British-born writer and artist), Rachilde (a decadent poet in the vein of Baudelaire, who was responsible for helping to preserve Wilde’s legacy after his death), and more. Many of these women wrote and believed entirely different things – Rachilde, especially, was despised by many of the early feminists for her portrayal of decadent womanhood. Yet all were welcome at Natalie’s salon. Perhaps the greatest tribute to Natalie came from the British writer Radclyffe Hall, whose novel The Well of Loneliness had been banned in Britain for its depiction of lesbian lifestyles. [4] In the novel, the main character (loosely based on Hall herself) is a lesbian torn by doubt and self-loathing caused by society’s rejection. In contrast to this stands the character of Valerie Seymour, based on Natalie. Her acceptance of, and pride in, her sexuality acts as a source of strength in the book. In Hall’s prose she comes to represent her own acceptance of her nature.

For Valerie, placid and self-assured, created an atmosphere of courage, everyone felt very normal and brave when they gathered together at Valerie Seymour’s. There she was, this charming and cultured woman, a kind of lighthouse in a storm-swept ocean. The waves had lashed round her feet in vain; winds had howled; clouds had spewed forth their hail and their lightning; torrents had deluged but had not destroyed her. The storms, gathering force, broke and drifted away, leaving behind them the shipwrecked, the drowning. But when they looked up, the poor spluttering victims, why what should they see but Valerie Seymour! Then a few would strike boldly out for the shore, at the sight of this indestructible creature.

This then was what Natalie Clifford Barney became – a symbol that to be a lesbian was not necessarily to be a tormented and unhapppy individual. Due to being banned in Britain, The Well of Loneliness became an underground bestseller in America (and indeed copies did turn up back in Britain). Since few of the works celebrated in Natalie’s salon were ever translated into English, the book became one of the few available in those countries to speak so unashamedly of the love that, back then, dared not speak its name.

Outside of her salon, Natalie’s life in the interbellum period was mostly occupied by her relationship with Dolly Wilde, niece of her childhood hero. [5] The pair met in 1927, when Dolly was in her early thirties and Natalie was on the point of turning 50. Their affair was best described as “passionate”, and seems to have involved almost constant argument. Dolly was an alcoholic and a heroin addict, who suffered from severe depression. Natalie tried to save her, but once again she was faced with someone who did not want to be saved. The pair were separated in 1939 by the war, just after Dolly was diagnosed with breast cancer. She died in 1941, either of the cancer or of an overdose of sleeping pills.

In the run up to the war Natalie was openly anti-fascist – unfashionably so for her set, as some guests at the salon commented. When war broke out she and Romaine Brooks moved to Italy, where they found themselves trapped in 1940 when Italy joined the Axis. It was an extremely dangerous situation for an openly lesbian woman with a Jewish grandfather. As a result, Natalie was forced to toe the line and wrote several anti-Semitic and pro-fascist pieces (though she managed to avoid actually publishing any of them). When Germany occupied Italy in 1943 and began deporting Jews to the camps, Natalie managed to avoid deportation (and reportedly used her American citizenship to save some of her neighbours). Later writers would use Natalie’s writings during the war to accuse her of anti-Semitism, but her actions seem to speak louder than her words on this occasion. It definitely seems to have come as a relief to her when the Allies liberated Italy in 1945.

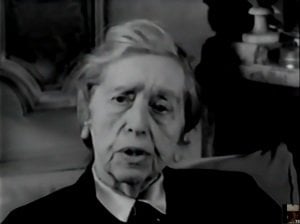

Following the end of the war Natalie returned to Paris, though Romaine chose to stay behind in Italy. She resumed her salons in 1949, though now she attracted writers more due to legacy of her salon rather than its weight in literary circles. Truman Capote was a regular during the time he lived in Paris, and Natalie’s contemporary survivors of the old avante garde, like Alice B Toklas, also became fixtures at the Fridays. She continued her “Women’s Academy”, and one of those she chose, Marguerite Yourcenar, would actually go on to become the first ever female member of the Académie Française’s ruling “immortals”. She remained in contact with Romaine Brooks, but as they aged their relationship became more and more strained -caused, naturally, by Natalie’s insistence on taking another lover. By Romaine’s death in 1970 the two had not spoken in some time, which was a source of great distress to Natalie. She died herself aged 95 years old in 1972, in her house in the Rue de Jacob, and was buried in her beloved Paris.

Natalie Barney’s legacy was diminished, in an odd way, by her longevity. By living into the 1970s she became a relic, and was sorely neglected by the “second wave” feminists who owed so much to her and her pioneering sisters. She appears, in literary disguise, in many literary works of the 1920s and 1930s, not just The Well of Loneliness but also the fiction of Djuna Barnes (who portrayed her as “Dame Evangeline Musset”) and Lucie Delarue-Mardrus (as “Laurette Wells”). It was Lucie who perhaps summed up Natalie’s occasionally contradictory nature best:

Perverse…dissolute, self-centered, unfair, stubborn, sometimes miserly…a genuine rebel, ever ready to incite others to rebellion…capable of loving someone just as they are, even a thief…

Indeed, it was Natalie’s willingness to accept others, even as she accepted herself, that was her greatest legacy. She remains more obscure than she deserves, but in 2009 she did receive one oddly fitting tribute in the city of her birth. A plaque in Dayton, Ohio honouring their unconventional daughter became the first in the state’s history to note the sexuality of the person it commemorated. Natalie, never ashamed of who she was, would have approved.

Images via wikimedia except where stated. Banner via Terres de femmes.

[1] Unlike Natalie, Eva was bisexual rather than exclusively lesbian. Her marriage to a Greek poet in 1907 led to the breakup of their friendship, though they did manage to reconcile much later in life.

[2] A Roman word meaning roughly “the demonstration of power through conspicuously extravagant spending”. This may have been meant as a dig at her father.

[3] Natalie would speak often of Mata Hari later in life, and did her best to counteract the popular image of her as a “femme fatale” with a more sympathetic view.

[4] The book, despite having virtually no erotic content, was still ruled as obscene in British courts on the grounds that seeking to promote tolerance of homosexuality was innately obscene.

[5] Not her only lover with Wildean connections – Natalie had a brief affair with Olive Custance, who went on to marry Lord Alfred Douglas. He is better known to scholars of Wilde as “Bosie”, the lover who prompted Wilde’s disastrous libel trial. Natalie, as was her habit, remained close to Olive and actually became godmother to the couple’s first child.