Review | Beckett’s Friendship by André Bernold

Samuel Beckett was an iconic writer for a number of years before his death and for all the years since. His plays and novels are spoken of and bowed down to by admirers and audiences. Some admit to absolute incomprehension when faced with the dilemma of Waiting for Godot, while others consider that the mouth in Not I, screaming out its terror and its life, is too alien for their own psyche.

In the preface to Beckett’s Friendship, the translator Max McGuinness writes of Proust, Barthes and Foucault’s assertion that knowledge of the author’s self is not necessary to any reader of any work.

‘What matter who’s speaking,’ Foucault said.

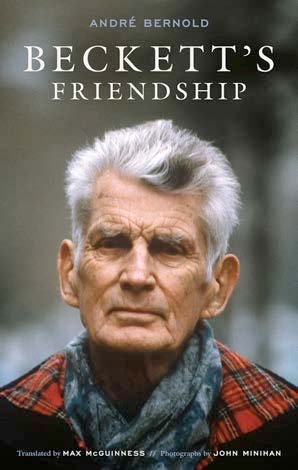

Beckett speaks to the underdog. He speaks to the utterly useless. He denotes the pain of the listless near dead. His life has been written about. His kindness is well known. His face has been made famous through photographs.

André Bernold’s Beckett’s Friendship 1979 -1989, a ten year account of his friendship with Samuel Beckett, is a beautiful book and written in pristine prose.

Beckett was famously taciturn and he and the young student André Bernold spent their first interview in near silence. ‘I remember that we were hunched forward a bit, so as to examine the deep breathing of this silence.’

How to conduct conversation amidst silence? He and Beckett resolved that by sending each other signals, quotes from other writers, German poems, and a postcard of a Flemish winter landscape.

Bernold writes: ‘We would contemplate, each man for himself, the nuances of ordinary finitude. There lay dehiscence, defeat and unravelling. That is where it was necessary to gather up the scattered threads and to calm the trembling, with patched mesh, with delicacy…Yes, I do want to be there, yes I wanted to speak to you, but look at how tired I suddenly am. Friendship, a hesitant surgeon, a puppeteer with uncertain hands.’

Bernold writes: ‘We would contemplate, each man for himself, the nuances of ordinary finitude. There lay dehiscence, defeat and unravelling. That is where it was necessary to gather up the scattered threads and to calm the trembling, with patched mesh, with delicacy…Yes, I do want to be there, yes I wanted to speak to you, but look at how tired I suddenly am. Friendship, a hesitant surgeon, a puppeteer with uncertain hands.’

The language is dense. The reader has to consciously immerse themselves into paragraphs that threaten to drown in words. Max McGuinness’s translation from the original French text is superb and so must also be congratulated for translating not only the words but the atmosphere of two men talking in near silence in a Parisienne café. However, some sentences and paragraphs take two or three readings before the reader ‘sees’ what Bernold is saying.

‘His gaze also used to open up spaces: I remember his voice the least badly when I think back to his eyes, which would catch up with the word, abruptly overcome in mid flight and prolong its vibration, attesting by their fixedness, the solitude of every vision, albeit retrieved from the depths, released, and free to disappear in the silence.’

Beckett’s work is famously ‘hard’ to understand and for a reader to negotiate their way through Bernold’s prose, there is relief at last: this part of Beckett, I see and I understand. Or I do not understand but I feel.

Bernold gives his own thoughts on Beckett’s appearance, his actions and his handwriting and even though this is only Bernold’s perception, and not the subject himself, he is lyrical in describing Beckett’s varied handwriting styles and the way Beckett opens a door. It is an intimate description of an aged artist trying to live in the world. However, there are episodes in this book where Bernold’s language obscures Beckett, as if Bernold believes that Beckett can only be understood through words that say too much rather than the minimum.

Bernold also dates Beckett’s actual utterances: ‘There is still a world to discover’ (12 November 1981). ‘I have nothing, I have nothing.’ (October 1985’), ‘My texts keep cancelling themselves out.’ (24th April 1981).

Of What Where, Beckett says, ‘It’s an old story that I don’t understand. I wonder what Where means. Maybe: where’s the way out? The old story of the way out.’ (13 May 1983)

[pullquote] It is an intimate description of an aged artist trying to live in the world. [/pullquote] Foucault’s assertion, ‘What matter who speaks,’ is correct to a point. Beckett did not want to be known. He shunned fame and as Beckett grew older and more arid in his talk, Bernold admits to seeking ways to fill in the silences with news of his own world; the old woman reading in her window late at night, his own dreams of death:

‘I would find myself in front of a bridge shrouded in fog, probably collapsed in the middle, and if I managed to cross it, the world was going to end. “May the Lord hear you!” said Beckett.’

There is humour when Bernold orders a whiskey instead of a coffee to drown out the tension and Beckett acts surprised: ‘You’re giving yourself up to drink…in the morning?’

The photographs by John Minihan are iconic but few. They add to the text and the presence of Beckett, although as readers we are reading from the outside in. Beckett is there but so is Bernold and it is one writer’s homage to another.

Only once does Beckett quote himself. He recites Clov’s exit from Endgame: ‘They said to me, That’s love, yes, yes, not a doubt, now you see how…How easy it is. They said to me, That’s friendship, yes, yes, no question, you’ve found it.’

This quote can be read as a frame for Beckett’s Friendship, and Bernold shows that he cannot separate Beckett from his work, and, in the end, neither could Beckett disassociate himself from his writings. He said of Westward Ho (1983) ‘It’s the last full stop.’ Yet he also said. ‘I still recognise myself in it.’

- Beckett’s Friendship by André Bernold (The Lilliput Press, €12). A copy can be ordered here.

Featured images via:

historicalwallpapers.blogspot.co.uk

lilliputpress.com