Caravaggio, The Man Without Hope Or Fear

Michelangelo Amerighi, who would achieve greatness under the name of Caravaggio, was born in 1571 in Milan. His father, Fermo Amerighi [1] was household administrator for a minor noble, the Marchese of Caravaggio, who lived in the city. When young Michelangelo (as he was christened) was five, the family moved out of the city to Caravaggio, a small town twenty-five miles from Milan. They were hoping to escape a plague in the city, though they may not have been successful, as Fermo died the following year. Young Michelangelo grew up in the small town until 1582 or so, when he left home to become the apprentice of a Milanese painter named Simone Peterzano. Around the same time his mother died. Michelangelo fell in with a rough crowd in the city, and it is around this time he adopted his personal motto, “Nec spe, nec mutu” – “neither hope nor fear.” [2]

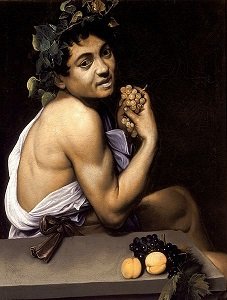

The exact details of how young Michelangelo left Milan are unknown, but he definitely left under a cloud. There were rumours that he killed a man in a brawl, and fled before he could be identified. All we know is that he turned up in Rome sometime between 1588 and 1592, without a penny to his name. What he did have was talent, however, and he was soon able to put that to good use. A practice of the more prestigious artists of the time was to establish “workshops” – painting factories where junior painters would create artwork after the style of the Great Artist, and then it would be sold as “from the workshop of”. The workshop where Michelangelo found work was owned by Giuseppe Cesari, a favourite artist of the Pope. Cesari was a practitioner of the incredibly stylized art form developed during the Renaissance and known as Mannerism, and it’s interesting to speculate how much of an impact being forced to paint in this style had on the young man’s later rebellion against it. His own personal style is evidently coming forth in his own paintings from the time, such as Young Sick Bacchus, a self-portrait painted while recovering from illness.

These paintings in his own style were all part of his self-marketing campaign, as was his adoption of “da Caravaggio” as a suffix to his name. The town of Caravaggio was obscure enough that the only real association it had for most people was with Polidoro Caldera da Caravaggio, one of Raphael’s pupils. Michelangelo began to market himself as “Caravaggio”, and it’s this name he is remembered by. Some time in the mid-1590s he became well-known enough to leave Cesari’s studio and begin selling his own works. These works, paintings mostly of his friends at the time, shed an interesting light on his circumstances. The subject matters is often criminal in nature. The Cardsharps, for example, shows a young man being cheated at cards – with a prominently displayed dagger offering a promise of violence if he detects the cheat. The Fortune Teller, a painting of a young man having his fortune told by a gypsy girl (while she steals a ring off his finger) wound up spawning dozens of paintings on a similar theme from other artists. In these paintings the men are modelled by Caravaggio’s fellow starving artists, while the women are local prostitutes. These were the only people Caravaggio ever felt at home with.

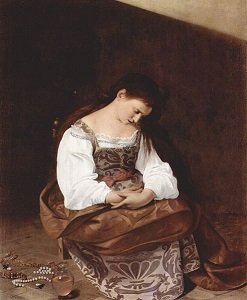

While his early paintings sold for a pittance [3] they swiftly built a reputation for the young man from Milan, they did their work in getting him a patron – Cardinal Francisco del Monte, a Venetian. For him Caravaggio created several works on “profane” themes, such as The Musicians, and Boy Bitten By Lizard. It was his first “sacred” work that prompted controversy however. Penitent Magdalene, showing the (apocryphal) moment when Mary Magdalene renounces her life as a prostitute in order to follow Jesus, was a huge break from the stylized overdone pattern of Mannerism. Instead it shows a woman sitting slumped in a chair, surrounded by jewellery she has removed and with a single tear running down her cheek. The raw emotion and realism in the painting is surprising even to modern eyes. To the people of the time it was almost scandalous. The woman in the painting was probably an actual prostitute named Anna Bianchini, and some art critics point to the evidence that she has suffered violence during her trade as a protest against the ill treatment afforded to prostitutes by the police at the time, and one historian even posits that her posture suggests having been recently whipped. It was, in short, an unambiguous salvo against the Mannerist establishment.

Caravaggio’s star was on the rise, and he soon began to attract the real moneymaker for an artist in Rome at the time – commissions from the Church. In 1599 he was contracted to to decorate the Contarelli Chapel, a subdivision within the church of San Luigi de Francesca (Saint Louis the French, better known as King Louis IX of France). Ironically the commission had originally been given to his old master Cesari, but he had drifted away from the job in 1593 and showed no signs of returning. Recent political developments between the Pope and the King of France meant that a flood of French pilgrims would be arriving for the Jubilee in 1600, and San Luigi de Francesca, dedicated as it was to a 13th century French King, stood to reap a windfall. Having one chapel boarded up would seriously cut into that, and so Caravaggio, through del Monte, got the job. The theme was St Matthew, and the first two pieces Caravaggio created (on his calling and martyrdom) were lauded for the artistry of his painting, and also for the way he used the architecture and lighting of the chapel itself to accentuate them. Though he missed his deadline by two months, he was still lauded for helping the church salvage a disastrous situation and his stock rose enormously.

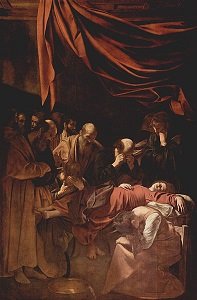

Over the next five years Caravaggio became one of the most famous, and most infamous, painters in Rome. With his realistic touches, it’s not surprising that he was frequently asked to produce work on darker subject matter such as martyrdoms and decapitations. While he completed a great number of prestigious (and lucrative) commissions, his first submissions were frequently rejected – his saints were too ugly, his theology suspect, and on at least two occasions his Blessed Virgins far too non-virginal. These rejections were hardly a disaster for him, as he would simply sell them to the nobles of the city, with the rejection adding a delicious taste of controversy to the purchase. His Madonna and Child With St Anne, showing a wrinkled St Anne (Mary’s mother) and a busty Madonna, prompted one Cardinal’s secretary to write:

One would say it is a work made by a painter that can paint well, but of a dark spirit, and who has been for a lot of time far from God, from His adoration, and from any good thought.

This may have been prompted by a knowledge of Caravaggio’s personal life. Though his income had increased, his company remained the same – the brawlers and lower classes of society. In 1603 he was put on trial for libel (along with Artemisia Gentileschi’s father Orazio, among others) after a rival painter, Giovanni Baglione, brought charges against him. This was an artists dispute that had begun when Baglione had painted “Sacred Love and Profane Love”, a painting which showed an angel interrupting a meeting (indeed, what appears to be a sexual liason) between a naked Eros and a devil. The Eros is a clear parody of the central figure from Caravaggio’s Love Conquers All, while the devil’s face is based on Caravaggio’s. The implication was pretty clear. Caravaggio’s sexuality remains a matter of great debate even today. It’s notable that he painted more than a few male nudes over his career, but not even a single female one. The painting was commissioned by the brother of the banker who had commissioned Love Conquers All, and was clearly intended as a family joke. However it triggered an intense rivalry between the two men that culminated in a booklet of poems ridiculing Baglione being circulated around Rome. As a result he sued Caravaggio and his friends for libel. Though he won the case, and the men were jailed for two weeks, Caravaggio took advantage of the trial to thoroughly rubbish Baglione’s work, saying:

I don`t know any painter who thinks Giovanni Baglione is a good painter.

The period from 1600 to 1606 was the height of Caravaggio’s crime, but it all came crashing down with the murder of Ranuccio Tomassoni. The exact details of the crime are unclear – the official story was that Caravaggio stabbed him in a dispute after a tennis match, but the more commonly believed explanation is that Tomassoni bled out after Caravaggio botched an attempt to castrate him. Why he tried to castrate him is another matter. The simplest explanation was that it was in a dispute over a woman (further complicating the murky waters of Caravaggio’s sexuality). Another theory is that as Tomassoni was a notoriously brutal pimp, and some of his girls were known to be friends with and model for Caravaggio, this may have been in retaliation for an attack on one of them. Whatever the reason, he had blood on his hands, and was forced to flee Rome in fear for his life.

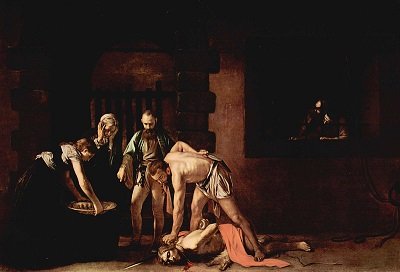

His first stop was in Naples, but though this was a lucrative city for an artist it seems to have rubbed him the wrong way and he only stayed a few months. His next port of call was Malta, where the martial Knights of St John, who ruled the island, found in him a kindred spirit. He was made their official artist and even inducted into the order of knights. He produced several works for them, the most famous of which is The Beheading of St John, showing their patron saint’s death. It’s notable as being the only work Caravaggio ever signed – his signature appearing in the blood flowing from the saint’s neck.

Though Caravaggio was happy in Malta, once again his violent temper ruined things for him. In August 1608 he got into a brawl with a fellow knight and seriously wounded him. By December he had been expelled from the order and from the island. He turned to his old friend Mario Minniti, who was living in Syracuse. The two men journeyed across Sicily, with Caravaggio’s fame winning him commissions along the route. Though he was well-respected, his mental state was clearly deteriorating. He saw enemies everywhere, refusing to undress for bed and over-reacting to any confrontation. Some scholars speculate that the lead-based paints he used were beginning to poison him, while others point to alcohol abuse or syphilis as possible causes.

Caravaggio returned to Naples in 1609 fearing for his life from unknown assailants; possibly associates of Tomassoni’s, or else of the knight he had wounded on Malta. His morbid obsessions show in two works he painted at this time: Salome with the Head of John The Baptist, and David with the Head of Goliath. In both cases the severed head is clearly Caravaggio’s own. His fears appear to have been justified, as there are reports that an attempt was made on his life in the city, with the news in Rome initially reporting he was dead. Later news made it clear that he was alive, though he had suffered facial injuries of some kind. Perhaps this news evoked some popular support for him, as rumblings began of him receiving a pardon for Tomassoni’s death – something he had been trying to obtain since he left Rome. With the pardon imminent, he left Naples in the summer of 1610. He never reached Rome. By the end of July word reached the city that he was dead. Accounts differ as to whether he was murdered or simply died of a fever. Researchers who found a skeleton they thought was his in Tuscany in 2010 say that he most likely died from a combination of sunstroke and syphilis, the latter of which would explain his deterioration. Though this is the most likely scenario, the fact is that we’ll never really know for certain how he died. The one thing we can be sure of is that he died as he lived: without hope, and without fear.

Images via wikimedia. Banner is a chalk drawing by by Ottavio Leoni, the only documented portrait of Caravaggio by another artist. Paintings mentioned but not shown have been linked, these may be NSFW.

{1] Or Merisi, or Merixio. Consistent spelling of names was not generally a consideration at the time, but Amerighi is the form that is still in use.

[2] The phrase was at the time a personal emblem of Isabella d’Este, a patron of the arts from Mantua. Her secretary wrote a book with the title, and perhaps that is where Caravaggio found it.

[3] At the time, that is. Nowadays Caravaggio’s paintings are worth millions. One, Nativity with St Francis and St Lawrence has the dubious honour of being the most valuable stolen artwork that was never recovered. Underworld rumour has it that it was badly damaged by rats while stashed, and the thieves were forced to destroy it to cover their tracks.