Queen Isabella, She-Wolf of France

The future Queen Isabella of England was born in France some time in 1295, as best we can tell. As the only daughter after three sons, she didn’t really account for much in her father’s scheme of things. Her father was Philip IV, King of France back in a time when France was almost more an idea than a country. He was also King of Navarre, which gave him a concrete power, and though some called him “The Fair” it is his other nickname that best sums him up – the Iron King. Philip’s character can be easily seen in his treatment of the Knights Templar and the Jews of France. After he had borrowed vast sums of money from both, he had the Templars accused of heresy and sodomy (which led to their grisly mass execution), while the Jews were banished from France on pain of death (while the King collected the debts that others owed to them). Despite his epithet, Philip was anything but fair.

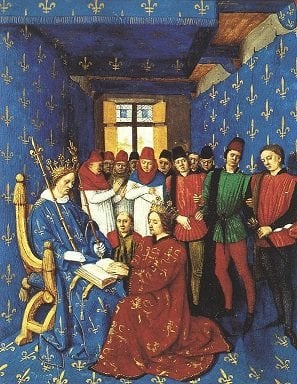

Isabella was said to be both beautiful (taking after her father in looks, which was the real origin of his nickname) and intelligent. But in those days the greatest value a daughter held to a King was not her own abilities, but her disposition in marriage. At the time France was engaged in a minor war with England for control of the duchy of Gascony, which was in reality a second front of the war between England and Scotland (in the first instance of what the Scots and French would later call “the Auld Alliance”). The first conflict was ended in 1298 by a truce, sealed with a marriage between the widower Edward I and Philip’s sister Marguerite. Though this developed into a true love-match it was not sufficient to keep the peace and war broke out again in 1300. This ended in 1303, and this time the wedding to seal it was between Isabelle and Edward I, in the hope that by ensuring the next heir to the throne would be half-French, the alliance would stick. [1]

Edward I would regret the pledged marriage and attempt to break it over the next few years. However when he died in 1307 the engagement was still in effect, and the following year the 12 year old Isabella was married to the 24 year old Edward II. It was not, at first, that happy a match. Edward had a “favourite” – a traditional English euphemism for the homosexual dalliances of some of their monarchs, which they (unlike any of their subjects) could enjoy, discreetly, without consequence. Edward’s favourite was Piers Gaveston, a Gascon nobleman whose involvement with him had so outraged Edward I that he had exiled the young man. On his death Edward II had recalled Piers, and made him Earl of Cornwall. Gaveston had served as regent while Edward journeyed to France to fetch Isabella, and on his return he openly neglected his young wife to spend time with Piers. Rumour had it that he even took some of her jewellery and gave it to Piers as a gift, and failed to give her the funds she needed to keep her own household staffed. Luckily for Isabella her father took this conduct as a personal insult, and on his admonishment Edward began to treat her with a little more respect.

Isabella was, as mentioned, an intelligent young girl. Initially she served as her father’s agent in Edward’s court, helping to drive a wedge between him and his barons. The wedge, naturally, was Piers Gaveston, who was exiled to Ireland. Once Edward began to treat her better she seems to have realised that acting against him was hardly in her own best interest, and when Piers returned she seems to have reached some kind of accommodation with him. Indeed, the barons soon began to regard Isabella and Piers as a common enemy, thwarting their own plans to control Edward’s reign. Isabella also began to build up her own network of supporters at court and became strongly allied with the de Beaumont family. Their French roots gave them common ground with her, and both Isabella de Vesci (a daughter of the de Beaumonts who became the head of Isabella’s ladies in waiting) and Henry de Beaumont (one of the greatest generals of the English army) would be key allies for Isabella.

The long war between England and Scotland continued throughout this time. Robert the Bruce, King of Scotland, was canny enough to avoid an open conflict that he knew he could not win. With his army drawn north, and his funds drained by conflict, Edward was not in a position to resist the powerful nobles of England, led by Thomas of Lancaster, when they began to demand more independence. [2] The 1311 Ordinances, as the demands of the barons became known as, were aimed pretty squarely at Piers Gaveston’s influence. The document they forced the King to sign banished him from the Kingdom, though it also included some reforms that in retrospect seem quite visionary, such as establishing a parliament. Of course, the King resented this and the following year he declared the Ordinances revoked and had Piers recalled. This looked likely to result in civil war, and the two sides began moving armies around England in 1312. Piers wound up besieged in Scarborough, and was forced to surrender on 19th May. The nobles besieging it swore him a safe conduct, but once he was captured (and against the protests of those nobles) Lancaster had him executed.

Edward, of course, was furious. He swore revenge against Lancaster, though he was in no position to take it. The nobles who had promised Piers they would protect him abandoned their support for Lancaster, and one of them (the Earl of Pembroke) was able to negotiate a treaty – Edward would let Piers’ murder slide, in exchange for Lancaster and the other barons taking their forces north against the Scots. In the meantime, Edward and Isabella travelled to France, at least partially to introduce King Philip to his new grandson. The future Edward III was born in 1312, and the presence of a male heir strengthened Isabella’s hand in court. It also helped to make the visit to France a great success, though it would turn out to have dire consequences for Philip’s family. As part of the ceremonies the two Kings knighted the sons of Philip, and Isabella gave her two brothers, and their wives, embroidered purses to commemorate the event. When the brothers came to visit London later in the year, however, Isabella noticed that the two purses she had given to her sisters-in-law were being carried by two knights of their household, and suspected they had been given as love-tokens. She mentioned this to her father when she visited him in 1314, and he had spies placed on the two woman and the two knights. Eventually he determined that they were meeting at an old guard tower (the Tour de Nesle) to commit adultery. The two men were tortured and executed for treason, the two women were sentenced to life imprisonment. [3]

1314 was the year of Bannockburn. This was a catastrophic defeat for the English forces in the war against the Scots. It led to Scottish raiding parties ravaging northern England for the next decade – an unfortunate return to the slave raids the Scots conducted against the north in the previous century. Another front opened in the war against the Scots, too – Edward de Bruce, younger brother of Robert, led a rebellion in Ireland that almost succeeded in removing English rule and establishing an Irish client-kingdom for the Scots. 1315 saw the beginning of a famine across Europe that lasted through to 1317 and would claim the lives of around 10% of the population. In the medieval tradition, a land beset by troubles was a sign of a king beset by God, and Edward became highly unpopular.

It didn’t help matters that he had a new “favourite”, Hugh Despenser the Younger, the husband of his niece Eleanor. The Despensers had their own enemies – among them Roger Mortimer, who had become famous for defeating Edward de Bruce in Ireland. Roger was a “Marcher Lord”, a descendant of the Norman earls who had been given land along the border with Wales. This led to them being highly militarised, and despited the conquest of Wales by the English a generation earlier they remained so. And they hated Hugh Despenser the Younger with a passion. Not only had he executed a Welsh rebel, Llywelyn Bren, who had surrendered to the Marchers on a guarantee of safe conduct, but he was known to be increasing his own lands and power by any means necessary. He had become unexpectedly wealthy when his wife’s brother died at Bannockburn, but this was not enough for him. For the previous few years Lancaster and his faction had controlled the court, but the Despensers soon gained the King’s ear and ousted them. In retaliation the Lancaster faction decided to raid the Despenser territories in Wales. Edward called for the Marcher lords to come to his aid – instead they joined the rebels. The Despenser Wars had begun.

Though Isabella had been able to reach an accommodation with Piers, she despised Hugh – and the feeling was mutual. When her old friend the Earl of Pembroke tried to end the wars by having her kneel and beg the king to exile the Despensers, she did it. The King was shamed, and forced into sending his favourite and his family into exile (where Hugh the Younger took up piracy as a pastime). Of course, he planned to bring them back as soon as he could. In order to manage this he sent Isabella on a pilgrimage to Cambridge, with a stop off at Leeds – a stronghold of Edward’s enemies. When they refused Isabella admission, Edward took it as a justification to reopen hostilities. This time things went far more his way, and by the following year Lancaster had been captured and executed, and the Despensers were firmly back in place in court.

Isabella still hated the Despensers, however – and this was confirmed when she was travelling in the north of England and was nearly cut off by a Scottish offensive. Under Despenser advice Edward had pulled back his forces and left an opportunity for the Scots to make a play to capture the Queen at Tynemouth Priory. Only the sacrifice of her squires allowed her enough time to flee to a boat in the harbour, and even then two of her ladies in waiting were killed by the Scots. She blamed Hugh and Edward for this, and effectively separated from her husband. The following year Edward demanded she take a loyalty oath to the Despenser faction, and when she refused she was barred from granting royal patronage. In 1324 things got even worse – the French members of her staff were arrested, her lands were all confiscated and worst of all her younger children were taken out of her household and given into the care of the Despensers. It was clear that she was going to have to take action.

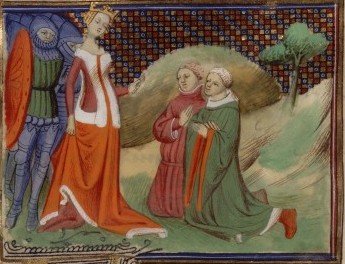

In 1325 her chance came. As a vassal of her brother King Charles IV for his French possessions, Edward was required to pay homage to him. This he had no wish to do, and kept delaying. Eventually Charles confiscated his holdings – a serious attack. Isabella persuaded her husband to send her to France with her son, Prince Edward, to pay homage on his father’s behalf. This he did, and the lands were restored. Once this was done, however, Isabella decided not to return home, much to her husband’s annoyance. Instead she began rallying the opposition to Edward, and even began dressing as a widow – claiming the Despensers had murdered her marriage. In Paris she met Roger Mortimer, the Marcher lord in exile, and the two became lovers. [4] Together they assembled an army of mercenaries, raising the funds by betrothing young Prince Edward to Philippa of Hainult in exchange for a dowry. She also made a secret pact with the Scots, invoking the Auld Alliance, to have them agree to hold off on England while she settled things. In September 1326 the She-Wolf fell upon England.

Isabella landed in Orwell with a small force, and immediately headed towards Cambridge. Local towns along her route mobilised their militias to meet the invading force, but when they found it was the Queen come to kick out the Despensers they swiftly changed sides. As she approached London rioting in supporter of her broke out, and the King fled west to Wales. Isabella brought her armies in pursuit. She laid siege to Bristol, being held by Hugh Despenser the Elder. The city also held her two daughters, Eleanor and Joan. The siege lasted just over a week before the Queen was reunited with her children and Hugh Despenser the Elder was parted from his life. They hacked up his body and fed it to the dogs.

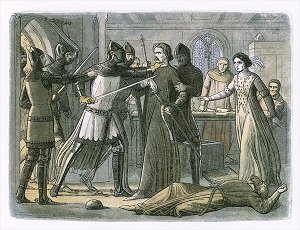

Edward and Hugh the Younger were now on the run, but bad weather off the coast left them with no avenue of escape. On 16th November they were captured. Hugh Despenser was sentenced to die on the 24th November in a brutal manner – he was stripped naked and inscribed with Biblical verse, half-hanged, cut down and castrated, had his belly opened and his guts drawn out, and then finally was hacked into quarters. The pieces of the hated noble were then sent out around England to be displayed in town squares. The Despenser regime was well and truly over.

That just left the problem of Edward. Queen Isabella had no wish to put her husband (who now, of course, hated her) back on his throne. However he was still king – at least for the moment. Isabella convened a council of nobles and had Edward officially deposed, but that didn’t remove him as a threat. They had him imprisoned in Berkeley Castle, where he suffered a “fatal accident” in September 1327. Most contemporaries believed Isabella had him murdered (in one account, by having a red-hot poker pushed up his rectum so as to kill him without leaving a mark), though some modern scholars think he may have actually died of natural causes. [5]

Isabella was now the regent for the young King Edward III, ruling England with Mortimer as her first minister. She concluded a peace with the Scots, one sealed with the marriage of her daughter Joan to Prince David, heir to the Scottish throne. The terms of this treaty did not sit well with the Lancastrians, her allies against the Despensers, and they rose up in rebellion. They were defeated, but it set the nobles against Isabella. Edmund of Kent led a conspiracy against her in 1330, ostensibly to restore Edward II (who he claimed was still alive) to the throne. He was caught and executed – a fiasco where the official executor refused to carry out the sentence on the flimsy legal grounds that were found, and another condemned man had to be pardoned and deputised to carry out the sentence.

Young King Edward III was chafing under his mother’s rule, and resentful of her lover Mortimer (who at times acted as though he were the true King). A rumour that Isabella was pregnant by Mortimer acted as the catalyst for the King to assert his rule. On 19th October a noble ally of the King led a force of 23 men through a secret tunnel into Nottingham Castle, where the royals were in residence. They arrested Mortimer and Isabella. The next month Edward put Mortimer on trial for treason, and sentenced him to death. In deference to his mother’s feelings, Edward had him given a clean death.

Edward could have had Isabella put on trial as well, but he chose not to. In Mortimer’s trial he painted his mother as an innocent victim, overawed by the Marcher lord. In fact he treated her very well, though she never wielded any real power ever again. She had a brief nervous breakdown following Mortimer’s death, but once she recovered he gave her a generous pension. She soon settled into the role of Queen Mother, travelling around England as she had during her marriage. She became a patron of the court, but managed to remain uninvolved in its politics, and was close to her children and grandchildren. In this retirement she regained her popularity, and became for many a symbol of the grandeur and elegance that the court could aspire to. In 1358, mourned by all of England, she died.

Isabella’s transformation into the “She-Wolf of France” began with Christopher Marlowe, who was fascinated by the rumours of Edward II’s sexual relationship with Piers Gaveston. In his play Edward and Piers are tragic heroes, and Isabella is one of the villains who conspire to destroy and kill them. Though the action of the play has little historical truth to it, it was a characterisation that would stick. In 1757 the poet Thomas Gray, writing primarily about Edward I, conflated Marlowe’s Isabella with Shakespeare’s description of Margaret of Anjou to label Isabella:

She-wolf of France, with unrelenting fangs,

That tear’st the bowels of thy mangled mate.

The narrative had been set, and the publication of Bertolt Brecht’s The Life of Edward II of England in 1924 (an adaptation of Marlowe’s play) only crystallised it for the modern era. The truth of her life, and the family life she enjoyed in her old age, all became brushed aside in favour of a one note characterisation, so much less messy than real life. Not too different from everyone else in history then.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] Of course, this had entirely the opposite effect – the English claim to the French throne this created became the grounds for the later Hundred Years War between Isabella’s son Edward and her cousin Philip VI.

[2] The ongoing push-pull between the British Crown and the powerful noblemen created by the Magna Carta would eventually culminate in the Wars of the Roses 150 years later, and only be ended by Henry VII’s brutal reassertion of the primacy of the Crown.

[3] Some historians suggest that Isabella could have had an ulterior motive for her accusation – strengthening her own child’s claim to the French throne. Regardless, one major impact was that tales of “courtly love” fell out of favour in the French court – romantic tales of royal adultery lost their appeal when the real thing had led to grisly execution.

[4] Not really a politically apposite move, as their relationship could have undermined their support from the English lords. However they don’t appear to have particularly cared.

[5] Some even credit the stories that his death was faked and that he escaped to the continent. Though this was a popular rumour for years afterwards, there’s little actual evidence to back it up.