Mental Health in Cinema – Inside Out, Song of the Sea and The Healing Power of Feeling

Apart from the acceptance of the LGBT community, there is one social issue in the last 2 decades that has seen the most evident and seismic shift in cultural attitudes towards it; mental health awareness. Although we see them on billboards and bus stops, the welcoming ubiquity of ads asking those suffering to “seek help” wasn’t always the case. Even if there are still some that need convincing, in recent times awareness about depression and other mental health problems are finally making the kind of impact on the public’s consciousness that it should have done many years ago.

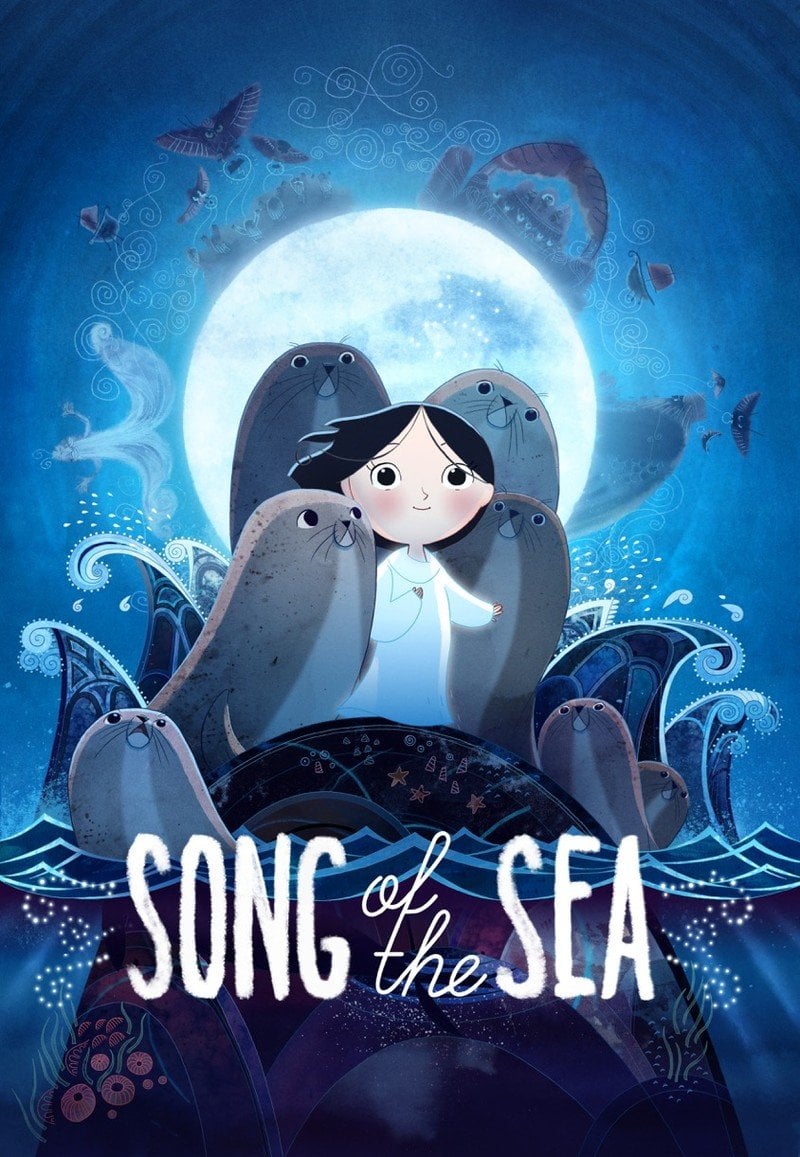

And what, you may ask, is the best indicator of progressive change in a societal way of thinking? The answer is what that society is willing to show and teach its youngest and most impressionable. And in 2015, we just happen to have been graced with two very good films aimed primarily at this audience that refreshingly promote, through a thoroughly modern prism, why openness can be so crucial to our mental well-being. The first was Pixar’s latest heart-string puller Inside Out and the second being Tomm Moore’s stunningly hand drawn, Irish export Song of the Sea. Write them off as facile cartoons if you must, but in them we find a more nuanced observation about this sensitive issue than we would in the majority of films that are supposedly aimed at a more ‘mature’ audience.

Inside Out and Song of the Sea were certainly produced in starkly contrasting surroundings, the former conceived by the multimillion dollar Pixar while the latter in the more modest micro budget environment of Cartoon Saloon’s studios in Kilkenny. The events which provide the emotional currency are also on very different scales, Song of the Sea being the apparent and sudden passing of a mother while Inside Out, which doesn’t need such lofty life destroying circumstance to get its audience to well up, just has its central character having to deal with making the “big move”. And yet these two share a simple but revolutionary message: Sometimes, it’s okay to be sad.

It’s a mantra that the Pixar animators take to a very literal and typically inventive level with Inside Out. The director is one Pete Docter, and anyone who has seen the 60 tears per minute montage of tragic perfection that opens 2009’s UP should already know that he doesn’t just deal in sad, but also excels in it. Docter and the Pixar team achieve this in their latest by realising the headspace of 11 year old Riley as a fully functioning world of its own, one that’s stability relies on Riley remaining emotionally balanced. In this cerebral culture there are, among other clever incarnations, whole islands dedicated to specific traits of Riley’s personality, a classic studio lot that exists solely to produce her oft-rainbow unicorn starring dreams and a headquarters in which the five manic manifestations of her primary emotions – Joy, Sadness, Anger, Fear and Disgust – preside in.

Unsurprisingly, these playful personifications take control at different times, influencing Riley’s temperament and how she interacts with others. In the films precious first few minutes, we see each of them taking the reins during Riley’s formative years in an opening montage that this time induces smiles instead of tears , but it’s clear that Joy (aptly voiced by an infectiously cheerful Amy Poehler) has the most abiding influence throughout this period. It’s only when her father has to take a job in San Francisco and she is uprooted from her familiar Minnesota life is the world of Riley’s head space thrown into disarray. The key scene occurs at her first day in her new school. Riley, as any 11 year old would, is left feeling stranded and alone in an alien environment and when she reminisces about a fond memory while introducing herself to classmates, she is overcome with emotion and starts to cry.

What makes this moment crucial, though, is not necessarily Riley’s mini breakdown that all can see but rather how the moment is represented in her mind. In the ‘ headquarters’, we see a literal struggle as Fear, Anger, Joy and Disgust desperately attempt to prevent sadness from acknowledging Riley’s true feelings, which eventually results in a sort of ‘mental meltdown’ with Happiness and Sadness being inadvertently expelled from the control room and shot out into the far flung regions of Riley’s mind. What follows is a standard “stranded and return home” story that we often see in animated fare, but the scene doesn’t just act like a catalyst for the plot but also for Riley’s ensuing turmoil. With only Fear and Anger to rely on, our prepubescent protagonist can only see a future of social anxiety, isolation and a life she feels she will never adjust to.

These two parallel running stories allow Pixar to have its cake and eat it too. While Joy and Sadness have the zany misadventures in the fantasy world within Riley’s head, the film is grounded by Riley’s tender scenes in the outside world. Docter was inspired to make Inside Out after noticing behavioural changes in his own daughter as she, like Riley, was making the difficult trek through tweenhood. He was so concerned with authenticity that even hired two prominent psychologists as consultants on the film and it pays dividends here. There are moments like the brilliantly observed dinner table feud, or when a father tries in vain to get his clearly troubled child to open up to her before bed, that ring with so much truth that they’d be the envy of a Spielberg or even a Mike Leigh film.

And then there is, of course, the emotional climax which must cement Pixar’s status as the abusive partner we naively trust yet keep going back to, knowing full well it’ll only end in tears. Both Riley’s tearful admission to her parents about missing her former life and Sadness finally receiving the acceptance from Joy and others are deeply touching moments that make you wonder why you just paid money to cry in dark room with strangers. When Sadness is finally allowed to get Riley to open up, the message isn’t just that we are allowed to be sad on occasion but also that all of our emotions can play a part in our well-being and that its essential that others are aware of these feelings. Telling kids something like that, and keeping them entertained, is far from an easy task.

Song of the Sea may not have the detailed and affecting characterisation that Inside Out delivers so easily but pound for pound it’s probably the better looking and sounding of the two. Moore and his team render the seascapes and countryside of Ireland with breath-taking results, often contorting the frames into living tondos of vivid colour that would rival even the most acclaimed of renaissance works. It’s a work of true beauty but also one that is, best of all, unmistakably Irish. The film’s story of two young siblings dealing with an apparent parental loss is interweaved with Gaelic folklore and its world inhabited by Miyazaki-esque creatures like Selkies, Faeires, spine-chilling witches and even an oversized sheepdog named after Cúchaillain. Like Inside out, the film opens with an enchanting first few minutes of familial tenderness with what is hands down the most adorable serenade made by a mother to her infant child in a lighthouse ever put to film (Lisa Hannigan provides her voice for both the mother character Brónagh and the haunting, ever constant score).

Song of the Sea’s Ben, like Riley, is a character that has trouble with healthily dealing with his own complex feelings. In the opening sequence his mother appears to have been killed on the same night that Ben’s sister Saoirse was born. Years later, a now six year old, mute Saoirse is living with Ben and her loving yet disconsolate father (Brendan Gleeson) in a lighthouse off Ireland’s coast. Ben can only seem to associate his younger sibling with his Mother’s disappearance and, as such, resents Saoirse unjustly. Instead of recognising his own pain, he takes it out on his sister, chastising her regularly and telling her old Celtic tales just to scare her before bedtime. It’s eventually revealed that Saoirse is herself a mythical seal-like Selkie and when she is abducted by the old witch Macha, Ben is made to confront not only the witch but also his own demons in order to save his sister. Song of the Sea is another film which has a habit of literalising things, with Macha’s nefarious owls turning people to stone by “bottling up” their emotions into jars for example.

When Ben reaches her cottagey lair, Macha can see the young boy’s suffering and offers take it away, citing that “there’s no use for such things that only cause pain”. Macha, as the mother of another Irish mythological figure, Mac Lír, is the mirror of Ben’s character in many ways. When her giant son endured a great tragedy, she turned him to stone to end his hardship and she herself is slowly enduring the same fate as she consistently bottles away any dark feelings that ever surface. Ben not only rejects Macha’s offer but after seeing what years of inadequately dealing with one’s true feelings can do, he realises the errors of his own ways. His course of action to save both the witch and his sister is to break all of Machas jars, releasing the trapped feelings within and forcing Macha to embrace them. It’s in the films emotional climax that Ben can accept both his own feelings and Saoirse for who she is – his sister. As far as metaphors for representing the need for the release of repressed emotion goes, it’s not exactly subtle but just because something is simple doesn’t mean it’s not effective. Even if you find it all a bit too thinly veiled, the scintillating artwork still speaks for itself.

Having two animated films, released in the same year, both openly dealing with a subject matter such as this could be nothing more than a coincidence but nonetheless it all feels rather timely. Since 2010, SeeChange reports that 91% of people now believe mental health problems can affect anyone, and this kind of consensus was unheard of as little as 10 years ago. This isn’t to say that having films like Inside Out and Song of the Sea is going to completely eradicate the stigma associated with mental illnesses or solve the problems we have still have with regards to adequate care and support for those suffering but it might just sow the seeds for a brighter future. One rather good film telling children that being open about their darkest feelings is a wonderful thing, but having two in one year, is a welcoming rarity.

Featuring image credit:

thefandom.net