What Darren Wilson’s New Yorker Profile Says About Race Relations in America

“Wilson has received several thousand letters from supporters, and he has written thank-you notes to almost all of his correspondents. Many of the letters are from police officers. Some are from kids. One card reads, “Thanks for protecting us!” Wilson proudly showed me a drawer, in his living room, which contained dozens of police-department patches from cops expressing their support. None of those cops, however, had offered him a job.”

On August 9th of last year, eighteen year old high-school graduate Michael Brown stole some packets of cigarillos from a shop in Ferguson, Missouri. Some time later, he and his friend Dorian Johnson were spotted by police officer, Darren Wilson, who blocked their path with his car. Brown and Wilson shared an altercation, which eventually resulted in Wilson firing ten bullets as Brown moved towards him. He was killed instantly. Wilson claims he acted in self-defence. Michael Brown had been unarmed.

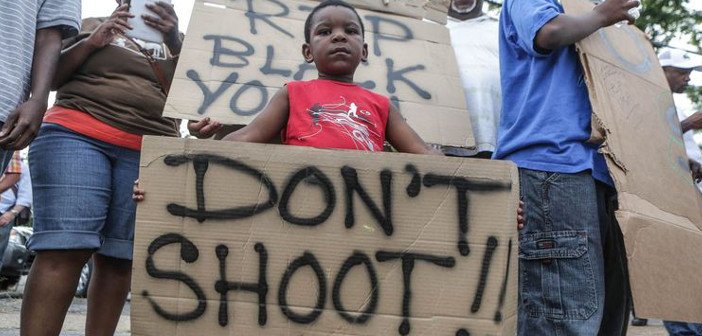

What followed Brown’s death were a series of protests in Ferguson, the introduction of the “Hands up, don’t shoot” mantra, country-wide debates concerning the authority of America’s law enforcement measures, and finally, public outrage as it was decided that Wilson would not be indicted for his actions. Yesterday, The New Yorker published a profile on Wilson, entitled ‘The Cop.’ Written by Jake Halpern, the article focuses on the ex-police officer’s early years and employment history leading up to the 9th of August 2014, the events of the day itself, and the impact the aftermath of the shooting has had on Wilson’s life. But reading the (really very quite long) piece, didn’t give me an insight into Darren Wilson at all. Instead, I found myself met with a conclusive portrayal of America’s historical treatment of race relations. It wasn’t just Wilson who was stating “Everyone is so quick to jump on race. It’s not a race issue” – it was society as a whole. It wasn’t just one man who was refusing to see the structural racism ingrained into contemporary life – it was millions of others across the country. [pullquote]Ferguson wasn’t just an isolated incident – it was an event that represented hundreds of years of black oppression; an event that said “Yes, it’s okay for the authoritative white man to kill the unarmed black man. He had probable cause, after all.”[/pullquote] Ferguson wasn’t just an isolated incident – it was an event that represented hundreds of years of black oppression; an event that said “Yes, it’s okay for the authoritative white man to kill the unarmed black man. He had probable cause, after all.”

It would be unfair of me not to commend Halpern on the immense amount of research, preparation and, arguably, objective reporting that constructs his profile of Wilson. However, it was difficult to make it through the article without getting the sense that I, the reader, was supposed to be feeling something akin to sympathy towards the man who shot Michael Brown. Wilson, after all, had been forced to move his family to a “nondescript dead-end street” near St. Louis after the shooting. He was finding it difficult to secure work in the police force again, after what had happened. He was now being forced to live “a quiet life.” All those attempts to trigger sudden compassion and understanding, suggestions that even though Wilson was a free man, maybe he was paying for what he did, and implications that justice had been served… And I was only a couple of paragraphs in.

Halpern spends a lot of time (approximately half of the article) discussing Wilson’s entry into the police force, his professionalism when it came to training, and his initial experiences in cities like Ferguson. Although, at times, this information did seem a little insignificant, it did reflect Wilson’s, and wider society’s, attitudes towards racial inequality. ‘The Cop’ may be quick to claim that Michael Brown’s death was not “a race issue,” but his acknowledgement of the ‘culture shock’ he experienced when he first started serving in poor cities with high crime rates rejects this assertion. When discussing the level of crime, and lack of well-paid work, in areas like Ferguson, Wilson states “That’s how I started. You’ve got to start somewhere.” This comment not only suggests that people only engage in criminal activity because they choose to, but also assumes that every single black person in Ferguson had the exact same opportunities as Darren Wilson – a white man from Texas. Suddenly, the idea that race relations played no part in Brown’s death, simply because Wilson didn’t intend to shoot a black man that day, becomes redundant.

This refusal to acknowledge America’s race divide can also be seen in the police force itself. Halpern makes sure to mention that on August 9th, only three black officers belonged to Ferguson’s force of fifty three. [pullquote]This alone, effectively mirrors America’s historical reign of powerful white men – whose racial supremacy is so fixed, and so systematically validated, they seem to think it’s their duty to control those below them.[/pullquote] This alone, effectively mirrors America’s historical reign of powerful white men – whose racial supremacy is so fixed, and so systematically validated, they seem to think it’s their duty to control those below them. Arguably, a police officer’s job is to do that very thing, but if that officer, and that police force, refuses to recognise the existence of such deeply rooted inequality, those relations will not be altered.

This racism is highlighted (quite clearly) on The Guardian’s website, where it is stated that even though more white people have been killed by police officers in America this year, black people are twice as likely to be killed while unarmed. Similarly, in their investigation of the Ferguson police department, the Department of Justice found that almost 95% of people arrested under ‘failure to comply’ charges were black. And if these stats weren’t enough, towards the end of his New Yorker profile, Wilson actually states that when he goes out to dinner now, he likes to “go somewhere—how do I say this correctly?—with like-minded individuals (…) You know. Where it’s not a mixing pot.” Yes, really. He said that.

But if a few statistics and a lot of police shootings aren’t enough to convince you that America seems happy enough shoving its race issues underneath the proverbial rug, perhaps Wilson’s actions after Ferguson will. Not only does he still seem to believe the shooting was necessary, but he also admits to using the mass amounts of donated cash from his ‘supporters’ to move house, while frequently responding to the warped ‘fan mail’ he is sent.

It’s probable that Wilson will never be forgiven, but maybe (just maybe), if he had shown any sign of remorse, any tinge or regret, or any disgust towards those who still commend what he did, it would be a little bit easier to understand the man who killed Michael Brown. But he didn’t. Darren Wilson still thinks that race had absolutely nothing to do with Ferguson – and alongside him, are a myriad of supporters who will read Halpern’s article, and think – “What a poor man. What an unfortunate victim of circumstance.” Unfortunately for them, and for dominant American society, they are absolutely wrong.

Images via:

bloomfieldreport.com

huffingtonpost.com

stlamerican.com

mic.com