The Open Book: Marcel Proust

It’s really difficult to write or talk about Proust without coming across as a pretentious and irrelevant toolshed. ‘Proust scholar’ has become a pop culture shorthand for the most useless type of individual imaginable. Without even being aware of it, you probably have a mind’s eye image – a wistful academic with a voice that walks on tiptoes, laments the passing of monocles, and can be sent into fits of sighing by the play of light on water. In a post-apocalyptic group survival scenario, there is no doubt that a Proust scholar would be killed and eaten first as the least necessary human. They probably wouldn’t even wait to run out of food.

All this is a pity, because honestly, sincerely – no joking now – everyone needs to read Proust. His one major novel, In Search of Lost Time, is the most insightful and emotionally overwhelming piece of art I’ve ever encountered, and his act of writing it showed astonishing determination and courage.

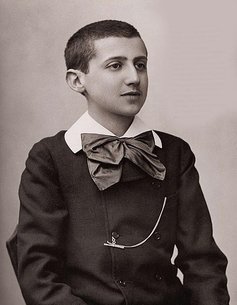

Reading about his early life is to be avoided unless you have some desperate need to exercise the wincing muscles in your face. Uncle Frank from Little Miss Sunshine has it right when he terms him ‘a total loser’. The son of a wealthy doctor, he lived off his parents until they died, and then off their inheritance until he died. He quite literally never worked a day in his life. His attempts at investing in the stock market floundered due to his tendency to only invest in businesses with pretty names. He was hypersensitive, plagued by asthma (or possibly just hypochondria depending on who you asked), and was terrified of his homosexuality being discovered and staining his reputation.

Young Marcel launched himself into high society with an obsessive desire to be liked that most people just found clingy and unsettling. He had a string of unrequited loves for various men, who he befriended and then barraged with long and effusive letters. On one occasion he missed a train to visit one such friend/ letter-victim, and was so distressed by this that he fell into a fit of uncontrollable weeping at the station, followed by a 19 hour asthma attack. The next day he sent him a letter explaining how this pain might bring them closer. Another time, he ended up sleeping with his friend’s mistress, just to feel closer to him.

Then, in 1909, aged 38, everything changed. With both his parents dead, he cut himself off from society and withdrew to his apartment on the Boulevard Haussman to dedicate himself completely to writing his masterpiece. He explained himself later:

‘When I was a child the fate of no holy figure seemed to me more miserable than that of Noah, who was confined to his ark by the flood for forty days. But later, I was often ill, and condemned to remain for long periods in an Ark of my own. It was then that I understood what a wonderful view of the world Noah could command from his ark, despite being shut in, and though darkness enveloped the earth’[1]

By 1919, when Proust’s latest releases were national news, this ‘Ark’ became the subject of much conjecture among the public. It was a special room – the type of room a super villain would live in – lined with cork to keep out the sounds of the city, and specially chilled to preserve his health. He and his housekeeper lived nocturnally, like two bats in a cave.

Summarising Proust’s Lost Time is really difficult (there’s even a Monty Python sketch about it), as it runs to over 1 1/4 million words, but here’s my attempt, much simplified. The novel follows an extremely sensitive narrator known only as ‘M’ (I wonder who that could be…) who grows up dreaming of one day entering aristocratic society, finding love, and becoming an accomplished writer. The novel charts his progress into, and disillusionment with, this society. Across 30 years he witnesses the loves, vicious squabbles, affairs, self-loathing, artistic successes, sad failures and personal implosions of a cast comprising of over 1000 characters. The reader is immersed in the codes, lineage, and fashions which this group use to snipe and belittle each other for social gain. And then you watch it all collapse as World War 1 begins. With a front seat view you get to experience how fleeting meaning and power can be, and how quickly all the social codes and morality that people cling to can become irrelevant and strange to a new generation.

Above all else though it just offers up, page by page, the most incredible insights into human psychology and memory that you’ll read in a novel. We’ve all had those moments – I’ll call them ‘popping’ moments – when you read of an experience and suddenly realise you’ve had that exact sensation hundreds of times but never seen it described before. There’s been this kernel of experience dormant in your memory, and the words of the author pop it open, and you see it clearly for the very first time, and you go ‘oh’. In an average novel you’ll get a few, in Proust they occur every other page.

Take this example – at one point the narrator returns home and spots an old woman in his house. Suddenly he realises it’s his grandmother, and that he hadn’t properly seen her in the years before now, and he realises:

‘We never see the people who are dear to us save in the animated system, the perpetual motion of our incessant love for them, which before allowing the images that their faces present to reach us catches them in its vortex’[2]

Or take this moment. when the narrator looks at his ill grandmother, and he realises how strange it feels to be aware of your body:

‘It is in moments of illness that we are compelled to recognise that we live not alone but chained to a creature from a different kingdom, whole worlds apart, who has no knowledge of us and by whom it is impossible to make ourselves understood: our body…to ask pity of our body is like discoursing with an octopus, for which our words have no more meaning than the sounds of the tides.’ [3]

A large number of Proust’s descriptions of memory would later be confirmed by neuroscientists as remarkably prescient insights into how we encode our experiences. The phenomenon of involuntary memory is sometimes called the ‘Madeleine effect’ or ‘The Proust Phenomenon’ in tribute to him. This is when a taste or smell reveals a memory, without any conscious effort, that Proust believed appears more perfect and complete than regular experience. This Proust reference from Ratatouille is probably the quickest, and cutest, version).

[pullquote]By 1921 Proust had become the most celebrated author in Paris following the publication of the first three volumes of his novel, but he became extremely anxious about the fourth volume, Sodom and Gomorrah. [/pullquote] Proust had become more comfortable with his sexuality, and he’d even invested in a male brothel in the Madeleine district run by his friend Le Cuziat, which he furnished with his dead parents’ old furniture. In Sodom and Gomorrah, Proust portrays a high society which is terrified of the way homosexuality crosses class boundaries, even making noblemen submissive to working class men. He shows a world where deviant sexuality forms its own order, like freemasons, within society, and where repression breeds isolation, self hatred and depression:

‘No banishment, indeed, to the South Pole or to the summit of Mont Blanc, can separate us so entirely from our fellow creatures as a prolonged residence in the seclusion of a secret vice.’[4]

This frank treatment of sexuality met with harsh criticism by some who claimed such things shouldn’t be discussed outside of medical textbooks, but in the decades that followed many gay and bi-sexual writers, notably Christopher Isherwood, were inspired by Proust’s controversial volume and his courage in persevering with it.

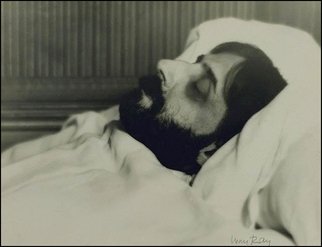

In the final year of his life he became even more obsessive about finishing and then revising his novel, often going without sleep and surviving only on café au laits. His final act on November 18th 1922 at the age of 51, was to try and rewrite one of the death scenes. The last three volumes, published posthumously, end by setting out a testament to art and outlining a philosophy through which to view it:

“Thanks to art, instead of seeing one world only, our own, we see that world multiply itself and we have at our disposal as many worlds as there are original artists, worlds more different one from the other than those which revolve in infinite space, worlds which, centuries after the extinction of the fire from which their light first emanated, whether it is called Rembrandt or Vermeer, send us still each one its special radiance.”[5]

Thanks to Proust we can see a world of special radiance, filled with rich emotions and insight, long after the extinction of that fire. So, for God’s sake, read the damn book.

[1] A night at the Majestic, Daven Port Hynes, p83

[2] p971, In Search of Lost Time, Scott-Moncrieff

[3] p1104, In Search of Lost Time, Scott-Moncrieff

[4] p618, In Search of lost Time 2, transl Scott-Moncrieff

[5] p254, Time Regained, Proust

Featured image via www.jrbenjamin.com