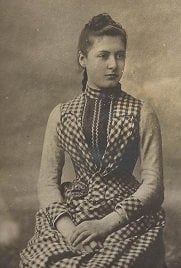

Marguerite Steinheil, Femme Fatale

There’s a strange golden age of Parisian life before World War I shattered the cosy comfort of their lives, and it’s an odd irony that one of its most infamous denizens was almost German rather than French. Marguerite Japy, known throughout her life as Meg, was born in Alsace in western France in 1869, but two years later Alsace was ceded to the German Empire in the treaty of Frankfurt. However the small area of Alsace where Meg was born, the Territoire de Belfort, was specifically exempted from the treaty due to the French ethnicity of its inhabitants and the resistance they offered to German occupation. So the estate of Edouard Japy stayed part of France, and so his daughter too remained French. On such things do the wheels of history turn.

Meg’s father, Edouard, came from a rich industrial family. He had split from them over their opposition to his marrying the daughter of an innkeeper, Meg’s mother Emilie. Perhaps it was her youth rather than her class that upset them – Edouard reportedly fell in love with her when she was only fourteen years old, and arranged for her to attend a boarding school in Stuttgart for two years before they were married. Meg, of course, adored her father and her autobiography paints him as the perfect gentleman. Of course Meg was, according to her governesses, a wilful child who would often get herself out of trouble through charming behaviour. At the age of seventeen she became involved with a friend of her brother’s, Lieutenant Edouard Sheffer, but her father broke the affair up before things went too far. Then, in 1888, Edouard Japy died of a heart attack. Meg, who was by now 19, was devastated.

The following year Meg went on holiday to the south of France to visit her elder sister Juliette, who lived in Bayonne. Juliette had married an engineer, and he introduced Meg to a friend of his, the painter Adolphe Steinheil. Though Steinheil was twenty years older than her he fell in love with her, and eventually persuaded her to marry him. Meg herself would later admit that it was more the prospect of Parisian society than Adolphe himself that persuaded her. The two were married in 1890, and Meg moved to Paris. Eleven months later their first and only child, a daughter named Marthe, was born. However shortly after Marthe’s birth Meg and Adolphe had a bitter falling out, and Meg investigated the possibility of divorce. Eventually (and ironically) she was persuaded to forgo the scandal and return to his house in Paris, but thereafter the two lived almost separate lives.

Of course, that’s not to say that Meg retreated into seclusion. Far from it – in fact, her life blossomed. Her salon became one of the fixtures of Paris society, and there she entertained many of the notables of the day. Painters, composers, philosophers and politicians all mingled beneath her roof in the Parisian tradition. Meg became celebrated for her beauty, and quietly notable for her love affairs. Perhaps out of a sense of guilt, many of her lovers bought paintings from her husband, which may have mollified him and certainly helped to finance her grand lifestyle. In 1897 she became the mistress of Felix Faure, the president of France, which ensured a steady supply of civic work for her husband in exchange for his discretion. But then, two years later, discretion became no longer an option.

On the afternoon of February 16th, 1899, Meg entered the Palais de l’Élysée, the President’s official residence, through a side door. The guards let her pass – she had been here several times before, after all. (In her autobiography, Meg would claim that her surreptitious visits were to help the President write his memoirs – a ludicrous story that is clearly not intended to be believed.) Shortly after she joined the President in his office, however, there were shouts that drew the attention of the servants, who gingerly entered the room. They found Felix dead or dying, apparently of a heart attack, though the exact circumstances became a matter of much debate. The least sensational had the President with his trousers around his ankles, while Meg stood next to him adjusting her clothing, while the most salacious had it that Meg was not only naked, but that she had been performing oral sex on the President when he expired and his fingers were clutching her hair so tightly that the servants had to cut her hair to get her loose.

Regardless, it was clear that the President was either dead or in the process of dying of natural causes (he would officially pass away a few hours later), and it was equally clear that his mistress had to be got off the premises before the press arrived. The guards quickly ushered her out the back. Though they did their best to hush the matter up, the nature of the President’s death soon became a common rumour. One joke at the time punned on the dual meanings of the French word “connaissance” as both “consciousness” and “acquaintance”, saying that a priest come to give the last rites asked “Is he still conscious?” [1] only to be told “No, she left out the back”. As a result, the whole affair became known as the affair of “la Connaissance du président”. Meg’s identity at least remained generally unknown, at least in the immediate aftermath. Felix had several mistresses, the most famous of which was the actress Cécile Sorel. Naturally the press immediately assumed that she was “la Connaisance”. [2] The truth became general knowledge a few years later, but it was enough after the scandal that it didn’t hurt Meg’s reputation.

Part of the reason it did not hurt Meg’s reputation was that among those who knew the truth, it fit Meg’s reputation to a T. In fact, the idea that she had driven the president to such a wild fit of passion that it had killed him enhanced her reputation enormously, and she had affairs with, among others, a French politician and future Prime Minister named Aristide Briand. By 1905, however, her husband was ailing and no longer able to earn as much from painting as he had used to. Funds were beginning to run low, and the lavish entertainments in her salon trickled to a halt. Her current lover was Emile Chouanard, who was a wealthy widower. With no wife to worry about, and well aware that Adolphe was not about to protest, he suggested that he and Meg rent a villa (with him footing the bills) in a discreet part of the countryside near Paris rather than deal with the hassle of a covert affair in the city. Meg agreed, and the relationship went well for a couple of years. In 1907 Emile ended it, possibly due to Meg becoming too possessive or possibly simply due to becoming tired of her.

Shortly thereafter Meg chanced to meet a young aristocrat named Emmanuel de Balincourt on the train, and by pretending a faint contrived to have him take her home. The young man was no match for her charms, and the two soon began an affair. However when she suggested that he follow the usual practise of having her husband paint him, he found the man he was cuckolding to be too sympathetic in person for him to continue the affair. This double rejection seems to have affected Meg greatly. She was entering her late 30s, after all, and her daughter Marthe had just become engaged to a young man named Pierre Buisson. Then she met a country mayor (and landowner of no small means, of course) named Maurice Borderel. He was, like Chouanard, a wealthy widower, and like Chouanard he had no compunctions about paying Meg’s bills. Unlike Chouanard however, for him this was no mere affair. He does seem to have genuinely loved Meg, and she even seems to have been fairly fond of him. However when she suggested marriage, he was forced to say no. He had three adolescent children, and had no wish to blight their marriage prospects by having a divorcee for a step-mother. So things stood, until the fateful night of May 30th, 1908.

On the morning of May 31st Remy Couillard, Adolphe Steinheil’s valet, woke and left his attic bedroom to begin his day. As he cam down the back stairs, he heard muffled shouting coming from Marthe Steinheil’s room – though he knew Marthe was away. On entering the room, he found Meg, naked, bound hand and foot to Marthe’s bed. She shouted at him that there were burglars in the house, and so he leaned out of the window and called for help. Two policemen heard his call and came running into the house, but they found no intruders. What they did find were the corpses of Adolphe Steinheil and Emilie Japy, Meg’s husband and mother, dead in the other two bedrooms. Meg, once untied, claimed that she was in her daughter’s bedroom as she had given her own bed to her mother, as it was more comfortable. The previous night she had been awakened by a gang in her room, three men and a red-haired woman, who threatened her with a pistol and demanded to know where “your father” kept his money. Meg had told them where the money was kept, at which point one of them struck her on the head. When she had regained consciousness she was tied to the bed, and on hearing Remy descend the stairs she had called for help. So were laid the foundations for a mystery.

There were several questions left unanswered by Meg’s version of events – most notably why her mother had been killed, while she had been spared. The lack of any substantial theft of property (both Meg’s jewelry and the family silver were untouched) also raised doubts. On the other hand, some evidence did confirm her story – not least that costumes matching those she said the burglars wore had been stolen from a nearby theater. However though Meg identified a patron of the theater as one of the men, he was found to have an alibi. In fact, Meg soon seemed to gain a mania for accusations – the first of which she levied at young Remy Couillard. When his clothes were searched she found a pearl that she said had been stolen, and when his room was searched she found a diamond that she also claimed had been stolen. However the distinctive pearl was recognised in the newspapers by a jeweller – who said that he had removed it from a ring for Meg almost two weeks _after_ the murders. The case against Remy was clearly a fabrication. Meg then accused Alexander Wolff, the son of her housekeeper, but this too turned out to be false. Their suspicions now fully aroused, the police arrested Meg in November 1908.

It was almost a year before Meg’s trial took place, due to multiple legal arguments, and by that point the case had become the talk of Paris. Mariette Wolff, irate at the accusation of her son, had told the authorities all about Meg’s many affairs. Their accusation was that Meg had killed her husband in order to clear the deck for her to marry Maurice Borderel. Bolstering this, they had discovered that Meg’s mother had actually died by choking on her dental plate, which she would not have worn to bed. Clearly she had died elsewhere and been place in bed. The trial was restricted to a hundred spectators, and competition for tickets was fierce. Notably the novelist Marcel Proust attended, astonishing his friends who had never seen him rise before noon before. Meg was the star attraction, and many agreed that a year in prison had taken the shine off her beauty. The trial began, and it became clear that the judge was against Meg, going through a list of her affairs (though President Faure was omitted). Meg handled herself brilliantly, admitting to fault where necessary, lying (for example, claiming her husband was unaware of her affairs) where she had to save her neck. She stuck to her story of the four black-clad intruders, and blamed all inconsistencies on the incompetence of the police. Her false accusations she put down to panic, and though she admitted fault she pointed out that she had already served a year in prison for a moment of madness. The prosecution attempted to make its case, but Remy proved an indecisive witness. The Wolffs, meanwhile, turned out to have regained their loyalty to Meg and refused to incriminate her. Of her lovers, Chouanard had left the country to avoid testifying, de Balincourt would not be drawn on their relationship, and Borderel turned out to do more for the defence than the prosecution. The middle-aged widower clearly still loved Meg, and the version of events he portrayed was far from what the prosecution had described. In a desperate move the prosecution then claimed that Mariette Wolff had been Meg’s accomplice, and the two had cold-heartedly murdered Adolphe and Emilie. The defence however pointed out the lack of motive for Emilie’s murder, and the weakness of the motive for Adolphe’s – clearly a woman embroiled in a notorious murder case would be as equally an unwelcome stepmother for Maurice’s children as a divorcee, for one thing. The jury took until 1.30am to reach a verdict, but when they did they found Meg not guilty on all charges.

Meg was released, though her notoriety made Paris a less than welcoming city, and she moved to London. There she used the name “Madame de Serignac” to avoid notoriety. Marthe was taken into the care of her father’s cousin and her fiance’s family, and forbidden to contact her mother. For several years the two were estranged. In 1910 however Marthe’s engagement was ended, and in 1911 she was reconciled with Meg, when Marthe married an Italian painter named Raphael del Perugia. In 1912 Meg wrote her memoirs (with the aid of a ghostwriter named Roger de Chateleux) – a somewhat sentimental whitewashing most notable for her embellishment of the aftermath of Faure’s death, when she claimed a mysterious government official came and confiscated the memoirs she had been helping the President compile. The government official was not unknown to her husband, she said, and she implied this had a bearing on his death. The same year Meg sued the publisher T Werner Laurie for publishing a book, Woman and Crime, in which the author Hargrave Adam accused her of lying at her husband’s trial. She won the case, the book was withdrawn, and publishers learnt to tread more lightly around “l’Affaire Steinheil”. In 1917 she remarried to Robert Scarlett, 6th Baron Abinger. He died in 1927, and Meg retired to Hove in Sussex, where she passed away in 1954 at 85 years of age.

And there we end, except for one interesting postscript. Among those who applied their mind to “l’Affaire Steinheil” was the famous French criminologist, Dr Edmond Locard. In a book on forensics in 1925, he used the case to show how different methods of strangulation could be mistaken for each other. As a police official, he presumably had access to classified material and his description of the affair casts a new light on events. His theory was that Meg had another lover, whose name had been kept out of the trial and the newspapers. When this man called unexpectedly at the house, he and Meg had quarreled. Adolphe had attempted to intervene and wound up struck in the throat, dying of a crushed larynx. Meg’s mother, coming upon the scene, suffered a heart attack and died. The lover, Locard would later add, was a foreigner, a close relative of the Tsar of Russia, who the government would have been anxious to shield from any scandal. Hence the entire crime and investigation, including Meg’s random accusations, had been a smokescreen designed to give the public a juicy scandal to hide the real events. The trial had been deliberately botched, in order to ensure that a guilty verdict (if returned) could be overturned on appeal. An interesting theory, and one that received corroboration nearly thirty years later. After Meg’s death in 1954, her ghostwriter Roger de Chateleux admitted that he had interviewed the doctor who autopsied Adolphe de Steinheil and Emilie Japy, and though the actual causes of death matched Locard’s theory he had been told to leave them out of his report for the trial. If so, perhaps Locard knew that he could speak without fear of reprisal since the Russia the lies had been spun to protect had come to an end eight years earlier. And perhaps la femme Fatale had inspired death to strike through misguided passion once more, only to again help cover up the truth. If so, it’s a secret that she took to her grave.

Images via Murderpedia except where noted.

This column was inspired by the description of Meg’s story in The Crimes of Paris.

[1] Literally, “is his consciousness present?”

[2] The death of the president had such an impact on the ongoing scandal of the Dreyfus Affair that several conspiracy theorists assumed the mysterious “Connaissance” was actually a hired assassin.