Young Irelanders | Review

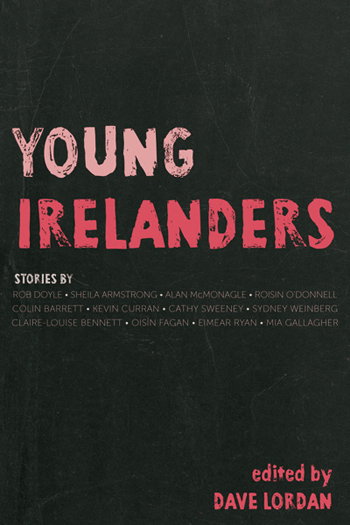

Young Irelanders, the name of this new anthology of short stories, is well titled with its echoes of the 1848 rebellion in famine-ravaged Ireland. In this year, a group of romantic nationalists and intellectuals heavily influenced by events in France and the broader continent made a stab at liberty from the crown. This reference is obviously intentional by editor Dave Lordan, who, in this exciting anthology, gives voice to the writers of the New Ireland, whose influences and scope extend far beyond the old literary guard, who, according to Lordan, wrote in a ‘melancholy naturalist mode.’

The renaissance of the short story form in Ireland in recent years is due perhaps to the popularity of M.A. courses in creative writing, and the emergence of world-class journals both online and in print, including the likes of gorse, The Penny Dreadful and The Stinging Fly. These lit-mags have provided a nurturing home for many emerging fiction writers, and acted as launch pads for writers such as Kevin Barry, Rob Doyle and Colin Barrett.

Anne Enright in her introduction to the Granta Book of the Irish Short Story (2010) writes that short stories are ‘the cats of literary form; beautiful, but a little self-contained.’ The cats in this anthology are a new breed of feline, screeching, feral and howling at times, as in Alan McMonagle’s outstanding story The Remarks; purring enigmatically à la Claire–Louise Bennett’s Oyster, and warring love cats in Rob Doyle’s experimental story Summer.

This anthology, carefully curated by Dave Lordan, is a delight, all twelve stories written by true disciples of literary New Ireland. Sean Ó Faoláin famously said that the things he likes to find in a story are ‘punch and poetry.’ In this collection the punch flows like the poteen in McMonagle’s story, and the poetry is lush and poignant in the prose of Bennett and Roisín O’Donnell.

Ireland has undergone seismic changes over the past decade and these profound cultural changes in our society are reflected in the dazzling prose and imaginative prowess of these authors. This anthology is a literary exposition of the state of our nation, one no longer constrained by conservative Catholic reins. This is a society embracing a new multiculture, struggling with the demands of the brave new world of social media, and reeling from the economic devastation of the past few years. This is the prose of recession not repression, an examination through the short story medium of what it means to be Irish now.

These structural changes in society are echoed by the innovative narrative framework of these stories, exemplified in the wonderful Doon by Colin Barrett and Subject by Oisín Fagan. I read them all in one sitting and let the variety of styles and voices wash over me and leave me with a vague sense of a truth glimpsed or tenuously grasped.

While the ‘melancholy’ may not be of the naturalist mode, there are certainly tears. In Alan McMonagle’s story The Remarks, the trio of bachelor flatmates cry rivers and weep inconsolably when they accidentally try some poteen-soaked bread. The bringer of the poteen to the bachelor enclave is Mary P., who tells the boys that ‘tears are the ultimate form of communication’. Later, as the trio prepare to go their separate ways, their year of self-discovery over, they decide to cry together one more time using the poteen and bread formula. One of the boys wonders where they’ll be a year later and another foretells a year of success and glamour for them all, one as a renowned musician, another a fêted dramatist and one as a celebrity chef. The tears gushed from them all then ‘as if there was no tomorrow’, flowing with existential dread and the melancholia of futile dreams.

Roisín O Donnell’s story How to Learn Irish in Seventeen Steps is the story of a girl from São Paulo who moves to Ireland with her boyfriend Seán and has to learn Irish in order to use her qualification as a Primary School teacher. We witness the irony of Luana trying to learn Gaeilge in a country where everyone she asks to help her retorts that they wouldn’t have a notion about Irish. Her boyfriend Seán only remembers the words for cake and sweets, cáca and milseán. Oisín Fagan’s Subject is ambitious in its exploration of what it means to be a young Irish man navigating the new millennium, “heterosexual, Caucasian, sub-bourgeois, Irish, post-peasant, empowered, lonely, distant when sober.”

This is an Ireland where there are no De Valera maidens dancing at the crossroads. In the case of Tanya in Kevin Curran’s story, Saving Tanya, a woman who gets tagged on Facebook engaged in a sex act sanguinely declares herself to be a celebrity, because in the aftermath she received one thousand friend requests. Claire-Louise Bennett’s Oyster is a poetic, surreal bath of prose from which the reader emerges with a sense of disquiet and an insight into the feelings of someone who is ‘ineffable and freakish and remote’. This startling new voice in Irish fiction nods stylistically towards Beckett and the 1950’s nouveau roman led by Alain Robbe-Grillet.

These stories also explore what it means to be Irish in a world dominated by consumer giants like Aldi and Lidl; cyber-bullying; Twitter grotesques, and pornography. Even religious archetypes like parish priests appear playing strip poker at a writers’ retreat in Eimear Ryan’s witty and resonant Retreat.

This new wave of Irish writing in the short story tradition shows the form adjusting beautifully to modern Ireland, able to convey a sense of life and reality with stylistic aplomb. The Young Irelanders rebellion of 1848 may have ended in defeat, but this anthology, exhibited with great tenacity by Dave Lordan and New Island, shows that the order is changing. The crown has landed on new heads. If this is a revolution in Irish short fiction, then vive la révolution!