WHY I BROKE UP WITH SEAMUS HEANEY, OR WHY IT’S GOOD TO BE UNCERTAIN

Let me ask you a question that you don’t have to answer.

Have you ever had a boyfriend who was really nice and really considerate, but with whom the sex was nonetheless not really amazing because he had a habit of doing things like taking off all your clothes – and all his clothes too – and then saying something very earnest like “I’m interested in your pleasure” or “I mean it, I really want to make you come” before setting about your genitals and breasts – if you have breasts – with some combination of hands and mouth and who knows even toys maybe in a way that is definitely pleasurable and would, had he not said what he said, probably make you come but because he said “I want to make you come” or somesuch you feel this pressure to feel pleasure which is stopping you from feeling pleasure because you need to be relaxed to feel pleasure and you can’t relax because you feel this expectation weighing you down as though the enjoyment you ARE getting from what’s going on is somehow invalid or unsatisfactory because you SHOULD be moaning and spasming already, why aren’t you moaning and spasming already, what’s wrong with you, and consequently the whole thing – while great on paper – just isn’t doing it for you?

That’s how I feel about Seamus Heaney.

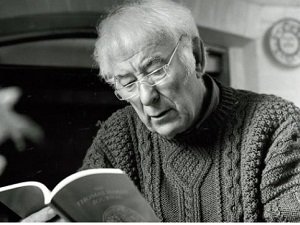

By anyone’s yardstick, Seamus Heaney is a great poet. He has a strong sensibility, an enviable clarity. He says precisely what he means. Clive James loves him because he is preoccupied with expressing things powerfully and concisely, what he – Clive James – calls “accessing bedrock”.

[pullquote] I am too conscious of the response I am meant to be having to have it. I should be sad, I should be glad, I should be at one with Nature, I should condemn our hypocritical society, and yet I’m not and I don’t. [/pullquote]All of these are positive attributes, and they are also exactly the attributes that stop me responding to Heaney. I am too conscious of the response I am meant to be having to have it. I should be sad, I should be glad, I should be at one with Nature, I should condemn our hypocritical society, and yet I’m not and I don’t. It’s all a little too self-conscious, too knowing, too calculated, too – and here’s the crucial word – too crafted.

All poetry is crafted, of course, it doesn’t spring magically from your subconscious onto the page. Someone, at some point, sat down and decided what words would be read or said. Much like a musical Impromptu is often a laboriously pre-composed piece, though, a poem can feel spontaneous and in-the-moment. A poem can rant, tease, question, wonder, work things out. Poetry’s deliberate, but it doesn’t have to deliberate.

All poetry is crafted, of course, it doesn’t spring magically from your subconscious onto the page. Someone, at some point, sat down and decided what words would be read or said. Much like a musical Impromptu is often a laboriously pre-composed piece, though, a poem can feel spontaneous and in-the-moment. A poem can rant, tease, question, wonder, work things out. Poetry’s deliberate, but it doesn’t have to deliberate.

You might offer the defence that a poet trying to express their own feelings, at least, has every right to be definite; after all, who knows better than they do how they feel?

[pullquote] Sometimes I think I’m really sad because true understanding and selfless love of another human being are – ultimately – impossible, and then I realise I’m just hungry. [/pullquote] I would respond that knowing better isn’t necessarily to know well. How certain can you ever be of what you feel? Feelings are vague. Am I nervous or excited? Horny or hungry? Sometimes I think I’m really sad because true understanding and selfless love of another human being are – ultimately – impossible, and then I realise I’m just hungry. We’re not always feeling what we think we’re feeling. I think.

In a previous article, I said that Gerard Manley Hopkins can take four lines to decide what he means. The lovely thing about the poet being occasionally unsure, I find, is that you can be unsure too. If they struggle to express what they mean, you become implicated in that process; you wonder along with them, you try to understand what they want to say but have not actually said yet. You become the friend who prompts the friend who can’t find the right words to express themselves; as such, the words of the poem are the starting point, rather than the terminal point. This is an active process. If everything in the poem is definite, taken as given, then I sometimes feel more like a passive recipient. Student in a schoolroom, more so than mate in a coffee shop.

Heaney doesn’t chat to his reader, I feel. He pronounces from the mountaintop. Emily Dickinson is another poet who leaves me cold for this reason. She has one register, and that register is Stating Facts. Did you know Hope Is A Thing With Feathers On? Did you know that After Great Pain, A Formal Feeling Comes? Some people say that all poetry is ultimately a conversation with yourself, but I’d quite like if it was also a conversation with the poet. If I wanted to be told facts, I’d go browse Wikipedia. If that’s what I don’t like, what do I like?

Sylvia Plath. I love Ariel, collection and poem both. The poem is one of my favourites; it’s content to describe moments – some violent, some not – and let you characterise the aggregate experience yourself. It has bags of confidence, but all of that confidence is channelled into constructing elaborate sounding relationships. Substanceless blue / pour of tor and distances. YUM.

Sylvia Plath. I love Ariel, collection and poem both. The poem is one of my favourites; it’s content to describe moments – some violent, some not – and let you characterise the aggregate experience yourself. It has bags of confidence, but all of that confidence is channelled into constructing elaborate sounding relationships. Substanceless blue / pour of tor and distances. YUM.

Kate Tempest. Give. It’s a command “Give me”, but it’s softened by the repetition; she knows what she wants, but not what to ask for. There’s something nice about list-based or schematic forms, because it acknowledges from the word go that this is an attempt at expressing something. If I haven’t gotten it by the end of this verse, then I can just do another verse to try and say it better. And this is a lovely, raw, honest poem which keeps building as it adds detail to one overarching feeling. The line “Give me a body that doesn’t hurt” always hits me hard.

Michael Ondaatje. Both a poet and a novelist, and the line I’m thinking of is actually from a novel. “All this Beethoven and rain.” This line closes Running in the Family, his novel about his family’s history in Sri Lanka. What I love about it is how it’s both mysterious and clear; I have an absolute sense of what I think it means, but would struggle to put it into words. It’s something about monsoon season and tempests and tempestuous emotions, but are his family the Beethoven or is the country the Beethoven and is it a specific piece of Beethoven or Beethoven the man? It’s open-ended. More, this is a line you can almost imagine someone saying on impulse without even knowing themselves what they mean, and then nodding at the rightness of it. It feels spoken. It feels alive.

Michael Ondaatje. Both a poet and a novelist, and the line I’m thinking of is actually from a novel. “All this Beethoven and rain.” This line closes Running in the Family, his novel about his family’s history in Sri Lanka. What I love about it is how it’s both mysterious and clear; I have an absolute sense of what I think it means, but would struggle to put it into words. It’s something about monsoon season and tempests and tempestuous emotions, but are his family the Beethoven or is the country the Beethoven and is it a specific piece of Beethoven or Beethoven the man? It’s open-ended. More, this is a line you can almost imagine someone saying on impulse without even knowing themselves what they mean, and then nodding at the rightness of it. It feels spoken. It feels alive.

[pullquote] Being 100% definite on everything you are saying can be good poetry, but it’s awful acting. It makes Shakespeare physically painful, and I love Shakespeare. [/pullquote] As a last note: I work in theatre, which may contribute to my feeling this way. Being 100% definite on everything you are saying can be good poetry, but it’s awful acting. It makes Shakespeare physically painful, and I love Shakespeare. A soliloquy spoken as a series of Lovely Images(TM), each given equal weight, is so Muller-Rice-ishly bland a purgatory that I nearly want to auto-Gloucester and gouge out my eyes just so that I’ll be less bored.

Declan Donnellan, in his deadly book The Actor and the Target, sums it up like this: if the speaker had said exactly what they meant, they would have stopped talking. If they haven’t stopped talking yet, then they don’t think you get it yet. In other words, they are not satisfied with what they have said. So, far from loving each Lovely Image(TM) equally, you should hate every single image except the last one. And even that last one probably isn’t great, it’s adequate at best, the most you can say is that we can move on at least.

I can never quite get this thought out of my head when I am reading poetry, and it means I can’t help but read Heaney’s measuredness as disingenuity. And so, I will leave you with four questions to ask of a poem and yourself.

When you read a poem, who is speaking to you? How confident is the poem of what it’s telling you? Do you believe what it’s telling you? Why?

(In fairness to Heaney, I think Mint is great. I really like Mint.)

I love this analysis. I found you post while Googling negative keywords about Heaney. He leaves me so cold and sterile. Reading his work is like a glass of cold water, clear and concise and does the job.But if i’m asked about my favorite drink, the drinks that made me drunk, or gave me pleasure, it’s never water. My favourite line of a poem is not from a poem, it’s from a Beckett radio play: Embers: ” Listen to the light now, you always loved light, not long past noon and all the shore in shadow and the sea out as far as the island.”