From Panel To Projection Booth |4| – Tarnished Silverware: The Birth of the Bronze Age

Part 4 of Eoin Rogers’ series on the history of comics looks at how social issues of the 1970s began influencing the stories of our superheros. Check out the rest of the series here.

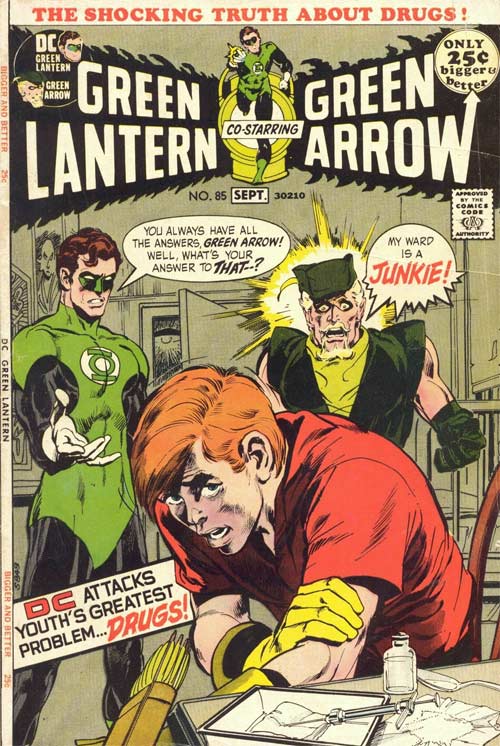

No doubt a reaction against the squeaky clean superheroes of the 1960s, things began to head in a somewhat more bleak and worldly direction as the last vestiges of the Silver Age were slowly tarnished throughout the 1970s. Unlike the Comics Code, which provided a handy segue from the Golden to Silver Age, the Bronze Age had no such unifying catalyst. No single date, time, or issue is attributed to herald the change from Silver to Bronze but the progression is generally attributed to a changing mood and shifting sensibility which, lacking the defined clarity of the Silver Age, sought to bring realism and relevance to the lives of the superheroic. Character deaths, changing artist styles, overtly social and political content, personnel changes at the different publishing houses, and the personal and professional failings of the once mighty superhero would all combine to define the Bronze Age. With the comic book industry still regulated by the Comics Code Authority established in 1956, nearly fifteen years on it was beginning to show that the Code was beginning to slip in terms of contemporary relevance. Comics were no longer just for children and a growing adult readership as well as driven creative staff began to steer comic books and superheroes into previously unchartered territory. This was evidenced in 1971 when Stan Lee ran a three part Spider-Man story which featured Harry Osborn developing a drug habit. The three comic books, The Amazing Spider-Man #96-98, were not Code approved, however Lee ran them anyway, seen as the controversial story line had actually been requested by the Department of Health who were looking to raise awareness about drug abuse and Lee felt this was ample justification without Code approval. Lee and publisher Marvel were chastised by the Comics Code Authority for essentially ignoring the Code but due to the publicity which the story received and thanks to the involvement of the Department of Health, the Authority revised the Code to include specific clauses concerning the depiction of drugs and drug use. Eager to jump on the Code approved bandwagon , two months after the Spider-Man story had been published, DC released Green Lantern/Green Arrow #85 in September 1971 which detailed how Green Arrow’s sidekick Speedy had developed an addiction to heroin and featured a cover drawn by Neal Adams showing Speedy cowering before his mentor with spoon, syringe, and dope on the table in front of him.

With the comic book industry still regulated by the Comics Code Authority established in 1956, nearly fifteen years on it was beginning to show that the Code was beginning to slip in terms of contemporary relevance. Comics were no longer just for children and a growing adult readership as well as driven creative staff began to steer comic books and superheroes into previously unchartered territory. This was evidenced in 1971 when Stan Lee ran a three part Spider-Man story which featured Harry Osborn developing a drug habit. The three comic books, The Amazing Spider-Man #96-98, were not Code approved, however Lee ran them anyway, seen as the controversial story line had actually been requested by the Department of Health who were looking to raise awareness about drug abuse and Lee felt this was ample justification without Code approval. Lee and publisher Marvel were chastised by the Comics Code Authority for essentially ignoring the Code but due to the publicity which the story received and thanks to the involvement of the Department of Health, the Authority revised the Code to include specific clauses concerning the depiction of drugs and drug use. Eager to jump on the Code approved bandwagon , two months after the Spider-Man story had been published, DC released Green Lantern/Green Arrow #85 in September 1971 which detailed how Green Arrow’s sidekick Speedy had developed an addiction to heroin and featured a cover drawn by Neal Adams showing Speedy cowering before his mentor with spoon, syringe, and dope on the table in front of him.

Comic book creators were beginning to bring a sense of social conscience to their work and in this way the characteristically zany and child friendly adventures of the Silver Age waned in the face of real world issues and political themes. While undoubtedly more overt and extreme in execution the Bronze Age actually mirrored some elements of its Golden predecessor. Many of Superman’s original adventures were centered around child labour and domestic violence. Even the cover of Action Comics #1 depicting Superman destroying a car for no apparent reason can be read as a reaction against the growing mechanization of the labour force which was taking place in America in the 1930s and 40s. Anthology style books, similar to those published in the 1930s and 1940s also experienced somewhat of a revival during the Bronze Age with the creation of titles like World’s Finest Comics and The Brave and the Bold featuring popular publication runs. There were also attempts to diversify within a predominantly Caucasian cast of characters. While Black Panther and Falcon, both created in the late 1960s, existed in the Marvel Universe, Luke Cage was the first black superhero to feature in his own solo title in Luke Cage, Hero for Hire #1, first published in 1972. Throughout the 1970s more heroes of black and other ethnic minorities were created like Cyborg, Iron Fist, Storm, and the Green Lantern John Stewart.

Existing heroes faced even greater personal challenges. As well as Speedy developing a heroin addiction Tony Stark developed a drinking problem fleshed out in the Demon in the Bottle story arc. Most challenging of all perhaps was the treatment of Spider-Man. In 1973’s Amazing Spider-Man #121-122 the imaginatively titled story arc “The Night Gwen Stacey Died” detailed the death of Gwen Stacey. Gwen’s death, while ultimately the result of the machinations of the Green Goblin, focuses more significantly on Spider-Man’s failure to save his romantic interest and his intense grief, and the sense of personal responsibility he feels for her death. With the death of the well-established love interest Gwen Stacey, it became clear that all characters, no matter how assured their survival was assumed to be, were no longer safe from death and the actions of our heroes no longer entirely infallible.

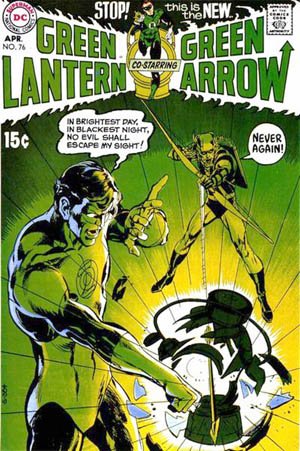

As the subject matter of the comic books began to grow more sophisticated the visual rendering of superheroes also began to change and grow which was chiefly seen in the development and use of a more photorealistic artistic style. Neal Adams is usually pointed to as the flagship artist whose work on Green Lantern/Green Arrow established what become recognised as the new house styles at Marvel and DC.

As the subject matter of the comic books began to grow more sophisticated the visual rendering of superheroes also began to change and grow which was chiefly seen in the development and use of a more photorealistic artistic style. Neal Adams is usually pointed to as the flagship artist whose work on Green Lantern/Green Arrow established what become recognised as the new house styles at Marvel and DC.

Growing maturity within the mainstream comic book industry was used to draw adult readers away from underground publications, known as comix, which featured overtly adult content. Comix, following on from a tradition of the highly pornographic Tijuana Bibles of the 1940s, were comic books for adults often featuring experimental artistic styles and explicit content. An underground movement which found traction with the counterculture of the 1960s comix were mainly distributed through headshops and independent bookstores. As methods of distribution continued to develop through the 1970s DC found that many of its titles from the 1940s, thanks to the limited resources of wartime America, were in high demand as the Baby-Boomer generation sought nostalgia titles. This lead the publisher to reprint anthologies and collections of older issues which would eventually lead to the necessity for specialized comic book stores, to which publishers could, and shortly would, directly distribute their comic books to.

Relaxation of the Comics Code also meant that publishers could return to genres which were previously prohibited such as crime, pulp, horror, and fantasy comics with titles like Ghost Rider, G.I. Joe, All Star Western, Swamp Thing, Conan the Barbarian, and Jonah Hex all proving to be popular. Previously banned monsters like vampires and werewolves were allowed back into the fold in the early 70s under the condition that they were handled with a literary sensibility reminiscent of Frankenstein and Dracula. Marvel even found a way of bringing zombies, which were still banned seen as they lacked the same literary history as other monsters, back into their books by creating the zuvembie, which is in no uncertain terms a zombie with a silly name.

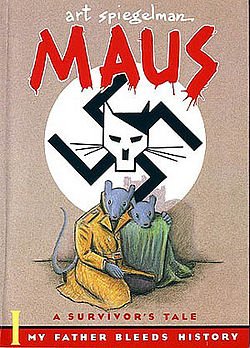

Towards the end of the 1970s creators like Will Eisner and Art Spiegelman and were experimenting with different forms to try and expand the scope of what and how stories could be told in comic book format. Widely popularizing the term ‘graphic novel’ Eisner’s A Contract with God dealt with ordinary people dealing with death, loss of faith, and disillusionment while Spiegelman’s Maus, the first comic book to win a Pulitzer Prize, began its serialized publication in 1980. Writers like Neil Gaiman and Grant Morrison would continue this trend of attributing comic books a literary bent.

Towards the end of the 1970s creators like Will Eisner and Art Spiegelman and were experimenting with different forms to try and expand the scope of what and how stories could be told in comic book format. Widely popularizing the term ‘graphic novel’ Eisner’s A Contract with God dealt with ordinary people dealing with death, loss of faith, and disillusionment while Spiegelman’s Maus, the first comic book to win a Pulitzer Prize, began its serialized publication in 1980. Writers like Neil Gaiman and Grant Morrison would continue this trend of attributing comic books a literary bent.

As readers grew up so too did their heroes. Superheroes were human now (except when they were aliens or ghosts or robots but you get the idea) and one by one they were dragged down to earth to suffer like everyone else. The Bronze Age marked a return to the social conscience which had been born in the Golden Age but was significantly bleaker than its direct predecessor the Silver Age. Developments in artistic style and mature content, as well as new means of distribution, were disrupting the authority of the Comics Code over the comic book industry and these innovations would eventually led to the publication of the first mainstream comic book to completely forgo the need of the Code’s seal of approval entirely, and the creator who did it first? A man whose name is as synonymous with contemporary comic books; Alan Moore.

Check back for Part 5 – Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing