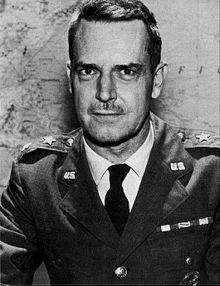

Edward Lansdale, Intelligence Agent

Sometimes looking into history is like being both short and long-sighted. Things far away are hazy, of course. Our sole source for a lot of early British traditions, for example, is the writings of the Romans who were conquering them. But that’s to be expected – details aren’t recorded, sources go missing, evidence is misinterpreted and so on. The blurring when we look at more recent events is of a different character. There, we have almost too many sources, and they all have an agenda we lack the distance to discern. Everyone always has an axe to grind, but at least 15th century historians can be pretty sure that the Tudors are a less than reliable source for the history of the House of York. Things become far murkier when we consider, for example, the role of the CIA in mid-20th century global politics. But that’s the pool we’ll need to dive into, if we hope to understand Edward Lansdale.

Sometimes looking into history is like being both short and long-sighted. Things far away are hazy, of course. Our sole source for a lot of early British traditions, for example, is the writings of the Romans who were conquering them. But that’s to be expected – details aren’t recorded, sources go missing, evidence is misinterpreted and so on. The blurring when we look at more recent events is of a different character. There, we have almost too many sources, and they all have an agenda we lack the distance to discern. Everyone always has an axe to grind, but at least 15th century historians can be pretty sure that the Tudors are a less than reliable source for the history of the House of York. Things become far murkier when we consider, for example, the role of the CIA in mid-20th century global politics. But that’s the pool we’ll need to dive into, if we hope to understand Edward Lansdale.

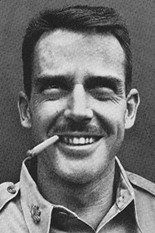

Edward Geary Lansdale was born in 1908 in Detroit, Michigan. His parents moved several times during his childhood, and he spent several years in New York before graduating from high school in California. He attended UCLA, where he earned money writing for newspapers and magazines as well as becoming a lieutenant in the US Reserves. After he graduated in 1931 he got a job in advertising, a profession at which he excelled. In 1941, when the USA entered World War 2, he applied for active service under his lieutenant’s commission. Due to his advertising experience he was pushed into the propaganda wing of the army, which was folded into the OSS later in the war. Once the war ended the OSS was broken up, and Lansdale (like many others) was sent to a remote posting, in his case in the Philippines. It is here that we leave behind definitive reality and enter the realm of Lansdale’s legend.

The first appearance of Lansdale in the annals of conspiracy theorists is immediately following World War 2. At the end of the war Japanese general Tomoyuki Yamashita surrendered to the Allies, and was immediately charged with war crimes related to the deaths of Filipino civilians during the Japanese occupation, including the “Manila Massacre” where over 10,000 civilians were killed. Yamashita was found guilty and hanged in 1946. A rumour persisted that while in the Philippines Yamashita amassed a huge fortune in war loot, and this loot was hidden away somewhere in the islands. There are various legends around what became of the loot, [1] but the one that concerns us was popularised by the writer Sterling Seagrave. Seagrave asserts that the gold was secretly seized by the US government after the location was tortured out of Yamashita’s driver, Major Kojima Kashii. The torture in question was supervised (and in some accounts, partially performed) by Captain Edward G. Lansdale. After the major broke and revealed the location, Lansdale verified the location of the four vaults he revealed and then flew to Washington where he conferred with General MacArthur and President Truman. The President is said to have decided to keep the loot’s recovery secret, and use it to create a fund for covert “black” operations by the CIA. Lansdale’s role in recovering the loot ensured that he would be involved in those operations for the next two decades. Naturally, this story is denied by official sources, does not appear in Lansdale’s official memoirs, and has no undisputed evidence to back it up.

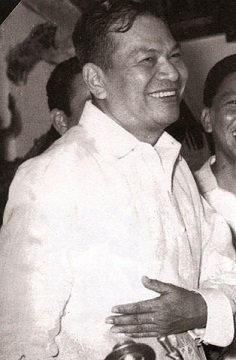

Lansdale’s official success in the Philippines was as a counterinsurgency advisor. During the Japanese occupation the farmers had formed a Communist-aligned resistance army known as the Hukbalahap (“Anti-Japanese Army”). They wound up conquering back part of the country from the invaders, and held it under their control as an independent state. After the war when the US took back primacy over the islands the former members of the Huks (as they were known) were considered too politically unreliable to be allowed to hold public office. Facing a crackdown from the government the Huks returned to the same guerilla warfare they had used against the Japanese, declaring their independence. Lansdale was a friend of the defence secretary (and later president of the Philippines) Ramon Magsaysay, and though he had returned to the US in 1948 he came back to the Philippines at Ramon’s request. Lansdale realised that an insurgency like this could not be fought in the same way as a conventional military action. The strength of the Hukbalahap came from popular support, and direct confrontation would only strengthen that support. Instead, if he eroded away the public’s trust in them while reinforcing their trust in the democratic government, then the Huks would be left isolated. This he did via a carrot and stick approach. The carrot came in the form of relief goods distributed by the Philippine Army, along with repairs to infrastructure and a purge of corrupt officers from the army and police forces. The stick was more subtle. The simplest was known as the Eye of God – suspected guerillas would have a menacing eye drawn near wherever they were staying, to symbolise that they were known and watched. Others used tactics that exploited the belief among the guerillas in the supernatural. In Lansdale’s autobiography, he recounts:

To the superstitious, the Huk battleground was a haunted place filled with ghosts and eerie creatures…When a Huk patrol came along the trail, the ambushers silently snatched the last man of the patrol, their move unseen in the dark night. They punctured his neck with two holes, vampire-fashion, held the body up by the heels, drained it of blood, and put the corpse back on the trail. When the Huks returned to look for the missing man and found their bloodless comrade, every member of the patrol believed that the Asuang [2] had got him and that one of them would be next if they remained on that hill.

Lansdale’s “psy-war” was a huge success, and the Huk rebellion fizzled out and faded away. In the end, it was the carrot of good government that proved more effective than the stick. Locally this was credited solely to Ramon Magsaysay, as Lansdale was keenly aware that to be legitimate all of the reforms would need to come from within. In 1953 Ramon was elected president on an anti-corruption platform, and in 1954 Luis Tupac, who was the most prominent leader of the Huks, voluntarily surrendered to the authorities. Unfortunately Lansdale wasn’t around to see it – he had been transferred to another country that was experiencing a Communist-aligned insurgency. Vietnam.

At first glance, the situation in Vietnam was similar to that in Korea, where the Korean war had just ended. Two governments, one recognised by the Communist powers, the other by the democratic powers. The difference was that in Korea, the two halves of the country had been formally separated since the end of the war. In truth, Korea had not been a whole country since 1910, when it had first been conquered by the Japanese, and the two governments that had formed in exile were what took over the halves of the country. In Vietnam, however, things had been a bit more fluid. The country had become a French colony in the 19th century, and though the Japanese invaded early in WW2, the fall of France and the establishment of the Vichy government meant that Vietnam remained under nominal French control. As in the Philippines, there had been a strong resistance by Communist factions, and this led to them gaining widespread support across the country. In 1953, when Lansdale arrived, the French were actually attempting to reassert colonial rule, and Lansdale was at first afraid that he would be expected to aid them. However that was not his mission. The Americans had seen the writing on the wall, and knew an independent Vietnam was coming. They hoped to make it one they could ally with.

Lansdale immediately diagnosed the core issue, which was that the Viet Minh in Hanoi was seen as a legitimate government that came from within, while the State of Vietnam was seen (correctly) as a French puppet state. The emperor, Bao Dai, even lived in France. Lansdale wrote in one memo:

There is general conviction that the Viet Minh has ‘national spirit’ on its side and that the Franco-Vietnamese forces do not. This is the result of successful psychological-political warfare by the Viet Minh. There has been no effective psychological warfare by the Franco-Vietnamese forces to expose this as a myth.

Lansdale was at the time working as an undercover CIA operative, with the cover of assistant Air Force attache to the US embassy. In this capacity he was able to call on the new Prime Minister, Ngo Dinh Diem. Diem was more well known and respected than Bao Dai, and the US hoped to develop the country into a European-style constitutional monarchy. Lansdale’s advice to the prime minister on developing a national army and introducing government reforms was well received, and the two developed a working relationship – though not the close friendship he had with Ramon Magsaysay. Lansdale’s main aim was to counter the perception of the national government as being French-controlled by convincing people that the Viet Minh were puppets of the Chinese. The first period of open war between the two sides had been ended by the Geneva Accords. This treaty set a timeline for national elections and established a 300 day “free movement period”. In this time citizens would be free to decide which side of the line they wanted to dwell. Lansdale saw this as key to ensuring victory in the following elections, as well as preparing the ground should warfare break out again. With the aid of leafleting and word of mouth campaigns, he spread rumours that two Chinese divisions had been brought across the border and were acting as conquerors, that the monetary reform the Viet Minh planned would destroy the local economy, and that the Catholic religion would be outlawed. Of these the first was false, the latter true and the middle a matter of debate, but the effect was what counted. Lansdale also tried some of his trademark appeals to superstition – distributing almanacs with horoscopes that foretold doom for the north and prosperity for the south – but that was less effective. More effective was a calculated program of rumours in the south that those who went north were being sent to China to work on the railroads. This all helped ensure that the net migration of Vietnamese was hugely in the south’s favour – around 900,000 by some accounts. The stick had been a success. Now everything hinged on the carrot.

In the south, efforts were being made to build a framework for a national state. At the time the country was largely controlled by different sects headed by warlords like notorious carbomber General Trinh Minh The. The General had been a thorn in the side of the French forces for years, and bringing him into the fold was a coup for the government. The next year, after war broke out, he was assassinated. Lansdale eulogised him as:

A good man. He was moderate, he was a pretty good general, he was on our side, and he cost twenty-five thousand dollars.

Everything was building towards the 1956 elections agreed in the Geneva treaty, which would reunify the two halves of the country. Unfortunately Ngo Dinh Diem was about to throw a spanner in the works by declaring that the Communists would not be able to participate in those elections, as he had no wish to risk losing power. The French, through Bao Dai, objected and Diem was officially removed from office, but this proved to be impossible to enforce. A referendum was declared to decide which of the two held sway. The opinion polls predicted a comfortable victory for Diem, and Lansdale urged him to run the vote fairly, but Diem refused. The result was returned as over 98% in favour of Diem – a clearly fraudelent result, and one that utterly de-legitimised the government. The alliance of sects fell apart, and the south fell into a bitter short war, as the new national army was used to put down the enemies of the regime. Diem turned into a de facto dictator, operating under the guise of democracy. Lansdale’s plan to win the hearts and minds of the people to this new government was wrecked, and he returned to the US. He came back to Vietnam in 1960, when the low-level conflict between North and South erupted into open warfare, but he never had the chance again to try to influence the course of the nation.

The remainder of Lansdale’s career is largely classified. He was heavily involved in US efforts to unseat Castro following the Bay of Pigs disaster. Strong rumours have it that he was involved the plot to commission Mafia hitmen to assassinate the Cuban general, as they had been heavily invested in Cuba before the revolution, though other stories have it that he was deliberately kept uninvolved – leading to embarrassment when he mentioned the possibility in an official memo, unaware of the risk of putting in writing what was already underway. Lansdale definitely headed up Operation MONGOOSE, a long-running CIA plot to keep Cuba in a state of constant turmoil, infiltrating small groups of saboteurs to sabotage power plants and sugar plantations.

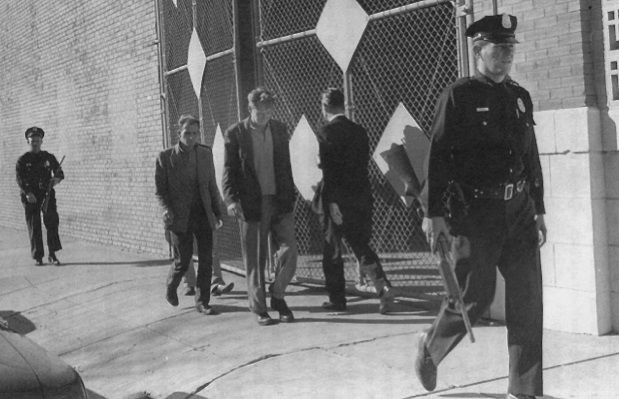

Lansdale retired (whether voluntarily or not) from the Air Force in 1963. Some conspiracy theorists point to this as a motive for him to be involved in the Kennedy assassination, though one would be hard pressed to find any political figure from the time who does not feature in any such theory. In Lansdale’s case, the accusations come originally from Leroy Fletcher Prouty, who was an Air Force colonel and an outspoken critic of the CIA. Prouty claimed that Lansdale orchestrated the entire assassination, and that he can be seen (with his face conveniently obscured) in the background of photos that show three tramps found in the area being arrested for questioning. [3] Prouty’s theories formed the basis for Oliver Stone’s film JFK, in which Prouty and Lansdale are both present as fictionalised characters.

Following his forcible retirement, and with the President now Lyndon Johnson (who disliked him), Lansdale was out in the cold. He managed to get a post in the US Embassy to Vietnam in 1965, but by this point the war was seen by most as a purely military engagement, and his concept of winning hearts and minds meant less to the generals than that of winning territory and victories. The Tet Offensive of 1968, a large scale attack across the entire front by the North Vietnamese troops, spelt the end for Lansdale’s plans – as he himself recognised, it undeniably militarised the war and in his view left the America commanders unable to distinguish friend from foe, ordering attacks that killed civilian and military alike. Lansdale commented:

I don’t believe this is a government that can win the hearts and minds of the people.

Lansdale left Vietnam in 1968 for the final time, and returned to America. In 1972 he wrote his memoir, In the Midst of Wars. An American’s Mission to Southeast Asia, though he only covered his career as far as 1956 – possibly due to the sensitive nature of his work, possibly due to a fire that destroyed a lot of his personal papers. He died of a heart attack in 1987. The following year Cecil Currey released a biography, based on interviews with Lansdale before his death, called The Unquiet American, which told the official story of his career. [4] The release of JFK three years later, the subsequent popularisation of Prouty’s works, and the release of official papers by the Assassination Records Review Board which shed new light on Lansdale’s activities in Cuba, all of these combined to make Edward Geary Lansdale a controversial figure, and one whose controversy survives to this day. Perhaps in another hundred years we’ll finally have enough distance to pin him down.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] My personal favourite being that it was found by a Filipino treasure hunter named Rogelia Roxas in the 1970s, after following a trail of treasure maps and accounts from war survivors. Roxas had a sample of the treasure analyzed, but when the president Ferdinand Marcos heard of it he had Roxas arrested and the treasure seized. In 1988, after Marcos had been deposed, Roxas sued him in Hawaii for the theft. He won an award of $22 billion (plus interest) based on the described value of the Japanese hoard. On appeal this was reduced to $13 million to represent that value of the specific treasure stolen from him, as the existence of the hoard could not be proved.

[2] A Filipino folk monster, similar to a vampire but with the ability to shapeshift into innocuous-seeming creatures.

[3] Prouty also claimed that the entire Hukbalahap rebellion was a CIA construct designed to turn Ramon Magsaysay into a folk hero and puppet President, and purge the Communist influence from the Philippines.

[4] The title comes from the belief that the character of Aiden Pyle in Graham Greene’s novel The Quiet American was based (at least partially) on Lansdale. Though the two never met, there are enough similarities to make it a distinct possibility.