How Whiplash Makes Me Want to Move to Montana

I want to talk about the medical risks of seeing the movie Whiplash.

Never have I exited a movie realizing ever more acutely the euphonious variety of mood disorders that I am suffering from. Daily existence should bring them out. It’s enough, isn’t it? The accumulation of a centrifugal cacophony of stresses from my personal life, work life as well as a seriously muddled interior life coming to a singular point should serve to induce deep anxiety attacks every hour or so. But I and the rest of the human race are resilient because, I believe, we give ourselves space. Space is how the riotous, contradictory intermingling streams of discourse can be allowed to crash into one another, reverberating their impacts into an ever-extending space.

Agoraphobia is the opposite of this. It’s an impairment of the vestibular system, interfering with our sense of balance, our spatial orientation. If you’re agoraphobic, you’re concerned about a lack of boundaries. About being lost in a space, being swallowed by it. I’ve heard adults suffering from agoraphobia trace it back to being lost as a child in a large, crowded place. Kirsten Jacobson writes that such a situation can make spatial separation from a secure base intolerable.

The opposite is claustrophobia, one that Whiplash makes good use of, which intensifies balance and spatial orientation. It stultifies all movement into precise points, almost extreme taxonomy, if you will. Too much security, in other words. Claustrophobia, which I suffer from, has to do with the fear of space being so narrowed and so specifically defined that there is no room for escape. No manner of escape, no possibility of flight will suffocate somebody who suffers from claustrophobia. In my own experience, it feels like the space is choking me because all I want to do is escape to a larger space where it doesn’t feel as if I’m being crushed to death.

If you’ve watched Whiplash and felt like I felt, then I want to say one of two things to you.

- You’re probably claustrophobic. Now you know and can get help.

- This essay hopes to pin down a couple of scenes to think about because working out the movie critically can be helpful to dealing with the anxiety it’s causing in you (also, because critically looking at something requires you to remove yourself from it emotionally, another method of escape, if you will).

Here’s an interesting observation that stoked the fires of my anxiety quite nicely: the movie’s shots all move from large to small. A close-up seems rather harmless, but you can overdo anything. Thankfully, the director appears to be doing it on purpose.

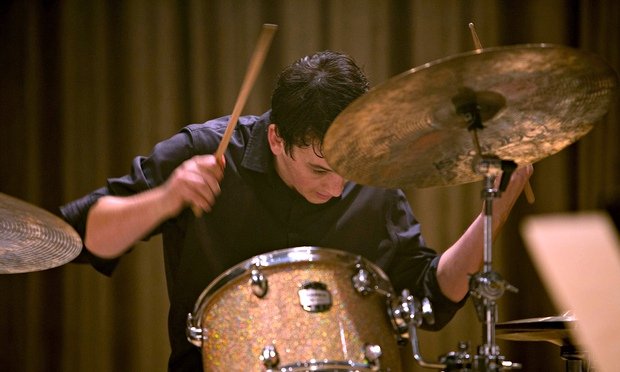

One of the quintessential scenes of the movie occurs when Andrew (played by Miles Teller) breaks up with his girlfriend Nicole (Melissa Benoist). As Andrew cites his hyper-logical bulletpoints for breaking up with Nicole, the camera focuses in on her face as his voice drones on in the background. Andrew’s eyes are vacant in the scene and he seems like a puppet, his voice being manipulated by some other (I can’t help but think of Fletcher, the conductor, a.k.a J.K. Simmons, as the ultimate puppeteer). It seems as if Andrew is almost possessed in that scene.

The scene draws the viewer in closer and closer. The director is forcing us to experience the absurd narrowing of space that began with a benign gathering of two people in a diner, suddenly becoming the camera’s focus on Nicole as a singularity. I assume she’s eating at a diner in some back alley in the East Village. And suddenly it’s like she’s on a billboard in Times Square. And why not? Her self is being reduced to the lowest reducible raw element. Her very presence, her very being, is an impediment to Andrew and she must be forgotten, dismissed, eliminated from the plane of his existence in order for him to go on being happy. Like some two-second advertisement you’d see flash across a screen in that glittering Babylon of advertising we call Times Square.

Pretty rough.

But the film also does it several times to Andrew. And that’s the problem he faces. He becomes a singularity. A frozen piece of music that can be played and played and played (by whom? You may ask. Fletcher, I would say). Let’s look at a scene focused on in the trailer. In a practice session with the band. The scene goes back and forth to close-ups of Fletcher as he anaphorically repeats the same direction over and over to Andrew, growing exponentially in disgust and impatience as his goal is not met. Then a close-up of Andrew as his failure to meet the goal weighs on him, focuses him even more minutely on something that he can’t quite see or reach. The goal will never be reached, of course. It’s an imagination of Fletcher. A neurosis that he has to push all people around him until he watches him break. (He’s got a touch of sadist psychopath in him.) And parallel to the break-up scene, the camera comes closely in on Andrew’s face as the pressure and narrowness of the experience breaks him. However, unlike the break-up scene where we only hear Andrew’s voice and watch its effect on Nicole, Fletcher’s presence can literally be seen as a shadow over Andrew. Fletcher is absolutely essential to Andrew’s own singularity as a being.

Unlike Nicole, who leaves the narrow space in disgust, demonstrating her own self-hood and refusing to live within the narrow space Andrew is affording her being (a mere impediment to his full self-development). Andrew cannot do it. In every aspect of his life, in fact. In the dinner time conversation with his family, the camera narrows in on him as he listens to the physical achievements of his cousins. As the shot expands outward, the only thing that Andrew can offer to differentiate himself within the familial space of the dinner table is a story about Charlie Parker told to him by Fletcher.

Interestingly, the story’s not exactly true. I mean Charlie Parker did have a cymbal thrown at him as Fletcher tells it; however, it was at his feet, not at his head. Slight though it may be, it shines a light on how desperately Andrew’s self-identification as a musician relies on the unhealthy admiration he has for Fletcher’s approval.

Andrew places himself on the periphery of his family – a pariah chasing an unreachable ideal, an archetype, a persona that is not even his but an imagination of sadistic personality who has lost the ability to see actual people. Referring to individuals by offensive sobriquets so that he does not have to approach them as individuals. Recreating individuals, in fact, into a form that he can process. One that fits in a small world completely under his control. You know, you never see him NOT in some sort of performance space.

Andrew plays for Fletcher and has no real motivation of his own. He remembers a motivation (when he looks at a video of himself as a child playing the drums), but the video is a strange document to him. His face seems puzzled, confused as he watches that video. He is someone’s creation now. No longer a child of his father, but an embodiment created by Fletcher, who never stops luring him into destructive situations (as befits the archetype of the artist that Fletcher is constructing). The films denouement is the best example.

Fletcher manipulates Andrew into returning under his direction even after physically assaulting him on stage during a concert and then leaving Shaffer Music Conservatory. (Not before costing Fletcher his job though.) It’s the best thing he could have ever done. Andrew returns to his own father, escaping the destructive paternal figure of Fletcher and actually creating space for himself. Rendering Fletcher to the margin, performing in a jazz band in a music venue located on a side street in New York City that he could’ve possibly never known about. But a street performer playing drums catches his ear and leads him to the venue where Fletcher meets him.

He entraps Andrew by asking him to play drums, so that he can humiliate him in front of a live audience and destroy any future that he could have as a musician. In essence, the ultimate fear of people suffering from claustrophobia, which is that the space will close in on them and kill them. No escape.

Fletcher’s humiliation, in fact, brings Andrew back to the earlier scene where he breaks into tears during a practice session. He is utterly reduced to a singularity of being and, like Nicole, he escapes to a wider space. The arms of his father, the space of his family and the entirety of his biography that transcends that narrow space of the musician archetype that, in many ways, Fletcher has helped create and sustains through the admiration he elicits from Andrew. An admiration Andrew gives freely under the illusion that it will somehow naturally develop him into the archetypal musicians (Charlie Parker, Buddy Rich) that Andrew worships.

In many ways, Andrew’s rebellion in the movie’s final performance, where he launches into a drum solo to lead the band in “Caravan”, appears on the surface as Andrew reclaiming himself. But the reclamation is through a piece that Fletcher has introduced to him that he reclaims himself. So it is not “his” self that is reclaimed, but a self that Fletcher has created. The last shot of Andrew lost in a manic fury juxtaposed to a previous shot of a horrified expression on his father’s face seems as if Andrew is escaping from all pulls and drags of control. As if he is going to destroy himself, but at least HE will destroy himself. Not so. The camera’s close-up of Andrew and the acceleration of the drum solo (controlled, of course, by Fletcher) shows that the Andrew we see at the end is a creation of Fletcher. He is not himself. His father does not even recognize him.

Ironically, the claustrophobia that the movie’s shots play with nearly swallows itself as instead of making the close-up shots a phenomenon that occur during emotional or physical distress (consider the car crash, an 18-wheeler rushing toward the Andrew trapped in the confines of his Sedan as well as trapped by the strict time table – or should I say time signature – he attempts to move within in one of the most destructive percussive pieces of the film). The close-up shot becomes the norm, the only thing left of Andrew at the end of the film. As the speed of his drumming increases, his physical deterioration is all too obvious as his sunken eyes and reddened, desiccated face indicate.

The crack of a snare drum is all that is left of him. His soul, as whatever inchoate levels or potentiality it possessed at the beginning of the movie, has been reduced to the rote slap of the sticks in the basic momma-daddy pattern of a beginner drummer.

When I left this movie, I still felt the tension in my muscles. Because the movie refuses to resolve it. “Caravan” does not easily resolve itself in tempo, but stops itself short and leaves us to ponder how to resolve. We become obsessed over it, much like Andrew, and there’s no way to resolve it. The piece, like the film, begins with crescendo and ends with a decrescendo, but we know from having seen the beginning of it that it will only end in another crescendo.

Much like Andrew, who cannot escape the daimon of the drum, we cannot escape the movie’s essentially manic infinitude. If you don’t know what I mean by “manic infinitude”, imagine accelerating in tempo infinitely with no apex, no conclusion. I had to smoke a cigarette and drink an espresso to unwind after the movie. Take a long walk. Forget about the whole thing.

But the fact that I needed to forget about it, seems to mean that I will never forget about it. And that’s what I loved about the movie and why I would advise people to be very careful about seeing it because if you see a late screening of it (if it’s still showing in theatres), then you won’t sleep.

You’ll just play it over and over in your head until you run screaming out into a wide, open field.