James Bloomfield Rush | A Will to Murder

James Rush was born in 1800, of what was delicately referred to as “uncertain parentage”. His mother, Mary Bloomfield (spelt as Blomfield in some texts) was the unmarried daughter of a tenant farmer, and she did not name his father. Some have speculated that he may have been an illegitimate child of a member of the local landlord family, the Prestons, whom he would spend most of his life entangled with. The most likely candidate is William Howes, a young man who had broken off an engagement to her and been sued (successfully) for breach of promise. If so, her unwillingness to name him may simply have been due to not wanting to marry a man who had previously spurned her.

Two years later she married John Rush, a successful local farmer, and he adopted the young James as his own. When James was eleven, his stepfather began renting a farm from the Reverend George Preston, the head of that landlording family, and when James was twenty four he rented a neighbouring farm. He had a forceful personality, and so the Prestons employed him as their bailiff and steward. In 1828 he married Susannah Soames, and they went on to have nine children. In 1837 the Reverend George died and his son Isaac inherited his property. Isaac had been named after an earlier Preston and it was the actions of that earlier relative nearly a century earlier that started the trouble that would end up with two men shot and another hanged.

The Jermy family were descended from Norman knights, which made them landed gentry rather than true aristocracy. They had lived in England since 1100 or so but by 1735 the family line was almost extinct. One of the few remaining members was William Jermy, who had married Elizabeth Richardson, the sole heiress to Stanfield Hall and the surrounding estates – which included the two farms that John and James Rush would later rent. She died and left him a childless but wealthy widower in 1750. William was notoriously feckless, and Isaac Preston (father of the Reverend George) was able to befriend him by taking on the management of his affairs. By 1751 he had persuaded William to marry his sister Francis and soon after the wedding the elderly (and not too healthy) William passed away. His will (drafted by Isaac) gave Frances a life interest in his estate and after her death it would go to one of two named Preston relatives. Both, died childless before Frances did, leaving the estate to fall to the residuary legatee. [1] In this case, that was defined as “the male person with the name Jermy nearest related to me (William) in blood” but by this stage there were no members of the immediate Jermy family left alive. A member of the Preston family (possibly an unnamed son of Isaac) stepped forward to claim the estate and produced affidavits where the two remaining distant relatives of William Jermy (who had since died) had sold over their interests to him for a nominal sum. (They were both day-labourers and doubtless had no idea what they were signing away.) Since there was nobody to object, this was accepted and Stanfield Hall became the property of the Preston family.

The unnamed Preston died five years later and the estate passed to his younger brother, the Reverend George. George moved his family (including the young Isaac) into the hall. In lip-service to William Jermy’s will, he gave one of his sons the middle name “Jermy”, and Isaac did the same, naming his eldest son Isaac Jermy Preston. When the Reverend George died in 1837, Isaac decided to move his family into the hall, and in order to finance refurbishing it advertised an auction of the old furniture and library.

On the afternoon of the auction, two men appeared from London. One of them, John Larner, said that he had come to “claim his family’s property” and that he, not Isaac, was the rightful heir to the Jermy estate. [2] He also pointed out that the will both included a provision that the library not be sold and that the person living in the hall should adopt the name and arms of the Jermy family. Isaac told him to take him to court if he felt he had such a strong claim and summoned the police to eject them. Despite his confident stance though, he quickly halted the sale of the library and legally changed both his arms and name to comply with the will (making his son Isaac Jermy Jermy).

In order to gain an official legal title to the policy, Isaac also made an arrangement with James Rush to sell him the property for £1000, and then bought it back for the same amount. This gave him a legal bill of sale to show his ownership. In return, he loaned Rush the money to buy Potash Farm, a freehold adjoining Rush’s current farm. In fact, Isaac had wished to buy Potash Farm himself and had sent Rush to buy it for him with orders to bid up to £3500 (based on a valuation from Rush). Rush however had put in his own bid of £3750 and secured the property. This, among other incidents, put a serious strain on relations between the two men, yet they seemed able to work together despite this. During the period that Rush “owned” the hall, Larner (who could not afford to go through the courts) came up from London with a group of friends. They occupied the hall by force, but after a few hours the local militia came up and arrested them all. They wound up on trial facing transportation but the sentence was dropped after Larner agreed to drop his claim to the estate. And so things quieted down – at least for the next few years.

In 1844, both John Rush (James’ stepfather) and Susannah Rush (James’ wife) died within a month of each other. John died from “the accidental discharge of a gun”, and though later people would claim that James had murdered him for his inheritance, there was little to support this. Susannah’s death, meanwhile, left him with nine children to care for. Though two were nearly grown up, some of the rest were only infants, and so he hired a governess to tend his family. The woman he hired, Emily Sandford, came from a well-off family fallen on hard times. Her father had been a businessman but had lost all of his money in railway speculations and so she was forced to go out and earn a living. She was very well educated and Rush was especially impressed with her skill in calligraphy. She was 23 when he hired her and he soon contrived (with a promise of marriage) to turn the relationship into a closer one than that of employer and employee. (In order to facilitate this, he even told her that he had called on her father and got his blessing for the engagement, though of course he had done nothing of the kind.) The result was that she became pregnant and gave birth to a child in early 1848, though the child died soon after it was born. Whether Rush ever truly intended to marry her became an academic question soon after that.

In 1847 the simmering tension between Isaac Jermy (formerly Preston) and James Rush finally broke out into open hostility. At this point Rush was renting two farms from Jermy but when he fell into arrears on the rent of one of them Jermy took him to court and had him evicted. Rush published a pamphlet that was a supposed report of the trial and in it he commented, “This fellow Jermy has no right to the Stanfield property”. The loan that Rush had taken from Jermy to buy Potash Farm would need to be paid soon and with no means to repay it he was likely to lose that property as well. Faced with this, he decided to take drastic measures. His first step was to send a letter to John Larner’s lawyer and arrange a meeting with him. At this meeting he claimed to be on their side in restoring the estate to the “rightful claimants” (at this stage settled as Larner’s cousin Thomas Jermy, since Larner himself was unable to act) and pointed out Emily Sandford (who sat some distance away) as a wealthy woman of his acquaintance who would back them financially. He extracted agreements from them to set his rents at a low rate in exchange and persuaded them to come up to Norfolk to finalise the agreement. This they did, signing papers with him and he made sure that they were seen by plenty of local people before they departed. Once that was done he then created several forged documents claiming to be written by Isaac Jermy, which offered to match those rents and give up the mortgage on Potash Farm in exchange for Rush’s support against Thomas Jermy’s claim. He pressured Emily to sign these as a witness, though she was not happy to do so. With that, his preparations were complete.

Over the course of November Rush had been careful to establish a precedent for his setting out at night to hunt for poachers. He made his son (who lived with him) a present of tickets for a concert in Norwich on the night of Tuesday 28th November and so on the Monday his son headed off with his wife and the house’s female servant. This left only Rush senior, Emily Sandford and a young male servant with the unlikely name of Savory. Rush then paid to have the paths around his house littered with straw, a common practice in muddy areas and one with the advantage of obscuring footprints.

The evening of the 28th he sat down for dinner with Emily Sandford, but she noticed he seemed distracted. When queried, he said that he could not stop thinking of the story of Robert the Bruce and the story of him being inspired to persevere by seeing a spider before the battle of Bannockburn. Eliza was disturbed by this, but he refused to be drawn any further. That evening, around seven or eight, she heard him leave the house.

Up at Stanfield Hall, nobody suspected the tragedy that was about to befall them. After dinner, as was his invariable custom, Isaac Jermy senior stepped out onto the porch for some fresh air. His son Isaac Jermy Jermy and his wife had gone to the drawing room to play cards. As Isaac stepped out onto the porch, a disguised Rush (who was hiding in the bushes) shot him twice. One shot pierced his heart, killing him instantly. Rush didn’t wait to check on his work but immediately entered the house through a side door. There he met Isaac Jermy Jermy in the hall, running to investigate the shots and killed him. His wife ran to her fallen husband and Rush fired at her. The ball passed through her arm and into her chest, wounding but not killing her. Before he could fire again one of the servants, a young woman named Eliza Chastney, grabbed her mistress and dragged her away. Rush fired after them but only succeeded in wounding her in the leg. Rush fled, leaving behind several notes which read:

There are seven of us here, three of us outside and four of us inside the Hall, all armed as you see us two. If any of the servants offer to leave the premises or follow us, you will be shot dead. Therefore, all of you keep to the servants’ hall, and you nor anyone else will take any harm, for we are only come to take possession of the Stanfield Hall property.

The notes were signed “Thomas Jermy, the Owner”. By this he hoped to sow confusion but the disguise he had worn (a wig and false beard) proved inadequate to the task. One of the servants recognised his profile and he was arrested. (In fact, the local police had already sent men to detain Rush even before this identification, as he was known to have quarrelled with the two dead men.) Rush had returned home around half nine, where he told Emily Sandford to say that he had only been out for ten minutes. Then he went to bed and collapsed. The police arrived while he slept and surrounded the house but they waited until a light was lit the next morning to move in and arrest him. They let him finish his breakfast before they took him away and he took advantage of this to stress to Emily to only say he had been out for ten minutes. Then the police took him away.

The initial judicial proceeding that same day was a somewhat unusual affair, as the two main witnesses were Mrs. Jermy and Eliza Chastney, both of whom were too severely injured to be moved. Instead the magistrates (after some consideration) brought Rush out to the hall and had the two repeat their testimony before witnesses. Both identified Rush as the shooter and remained firm even after he asked them several questions. In court the next day Emily at first stuck with her initial story but when cross examined admitted that she had been reading a book and was unsure of exactly how long he had been out for.

Proceedings were then adjourned until the Saturday but the judges considered (much to Rush’s dismay) that enough evidence had been heard to remand him to custody until then. On the Saturday Emily Sandford was once again called and this time her testimony was far more detailed. She had clearly decided to make a clean breast of it and said that not only had Rush been out for at least an hour and a half but that he had told her to lie and say that he had only been out for ten minutes. Over the next week a total of thirty two witnesses were called, testifying to Rush having been enquiring to make sure the two Isaacs were in the hall that night and to a disguise being found in his house. Emily Sandford was re-examined twice more and on both occasions Rush became so violent he had to be taken from the room. On this evidence he was committed for trial.

The trial was a media sensation, with the circumstances surrounding the affair having enough melodrama and recondite detail to fill a huge number of column inches. The documents that Rush had hidden in his house, both the genuine agreements and the forgeries, were entered into evidence and the forgery was easily detected. These showed that the death of the two Isaacs would leave Rush with a legal ground to claim free title to Potash Farm as well as reduced rent on his other two properties. Emily Sandford gave her evidence, and the sight of her weakened state gained her a great deal of sympathy.

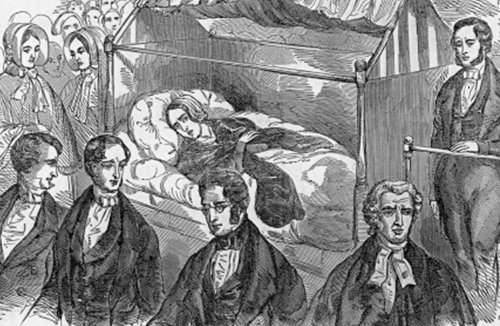

The media delightedly portrayed her as a good woman drawn astray by the evil Rush and her evidence (including the revelations about her signature on the forged documents) was damning. Almost as damning was Rush’s conduct in cross examining her, as he seemed far more focused on her betrayal than her evidence. The highlight of the trial was Eliza Chastney. She was brought in to court on a litter to give her evidence and she was positive in her identification that Rush, and no other, was the man who had been in the hall. Rush gave his own defence but could offer nothing to offset the weight of the evidence against him. The jury returned a guilty verdict within five minutes and the judge sentenced Rush to death.

One week later Rush went to the gallows. Funds were set up for public subscription to benefit both Emily Sandford and Eliza Chastney, both of whom had received sympathetic coverage from the press. Nearly a thousand pounds was raised for Emily, though she claimed only £600 of it to pay for her and her brother to emigrate to Australia. Her brother, tragically, drowned during the trip, but Emily made it to Adelaide. The following year, she married a German merchant and eventually moved to Berlin.

Eliza Chastney’s fund raised around five hundred and sixty pounds, including a £25 donation from Queen Victoria. She married a carpenter and moved to Cambridge, where they raised a family together. Stanfield Hall and the Jermy estate, the source of so much misery, passed down to Sophia Jermy, the granddaughter of Isaac Jermy senior. Thirty years later another claimant came forward, George Taylor, looking to inherit under the 1751 will of William Jermy. The judge ruled that the statute of limitations had passed and so (despite the belief of everyone named Jermy in the country that they were doubtless entitled to the “Jermy Millions”) the matter was finally closed.

Images via wikimedia and the Jermy family website.

[1] The person who gets whatever is left in value of an estate once all named sums have been doled out. A popular device in detective fiction is for a residuary legatee to apparently be getting very little money, but actually to be in line for a huge fortune that nobody was aware of.

[2] The other is sometimes given as a cousin of his named Thomas Jermy (and the actual claimant who he was speaking on behalf of), and sometimes as a friend of Larner’s named Daniel Wingfield. Given later events Wingfield seems most likely, but there is no way to be sure.