Rest In Pixels: How will you be remembered?

In Loving Memory

My great-grandfather lived and married in South Africa, where he made his fortune working in the diamond mines and building houses. Returning to Ireland, he founded two businesses. When he refused to remove the family name, written in Gaelic, from a business façade, the Black and Tans burned the place to the ground. W.H. O’Connor was then forced to leave the family home and go on the run, from where he corresponded regularly with Éamon de Valera, petitioning for the independence of the Irish state.

These are the details of W.H. O’Connor’s life, which we, his descendants, have been handed down. This story is proudly repeated, the finer points shaped by telling and teller. I have seen pictures of the man on his wedding day and a photograph of him, in a three-piece suit, standing straight-backed outside a glasshouse in the sun. Everything I know about him has the sepia tone of those old photographs, warming in the hazy, flattering glow of communal family memory. In the broad brushstrokes of my family’s account, we remember W.H. O’Connor as a wander-lusting entrepreneur with immense fortitude of character and a vast intellect. His is a narrative of intrepidity and unorthodoxy, of pushed boundaries, unyielding principles and latitude of mind.

This narrative carries great weight: his story has filtered down into my understanding of who I come from, who I am, and who I can be. In the full knowledge that this narrative is just that: a story, whose relation to the actuality of the man’s life is clouded by time, memory and sentiment; it is no less potent. Indeed, it may be that the selectivity and imprecision of these memories of W.H. O’Connor’s life are those which enable us, his descendants, to best live in his wake, spurred to achieve and better ourselves in our lives by soft-focus accounts of the man and the life he lived.

Forgetting is Forgiving

Forgetting is Forgiving

From the moment they are forged, human memories are in a state of decay. We need to work hard to forestall this forgetting process and save some memories from the plughole. Though a seemingly annoying glitch in our make-up—particularly when we can’t remember a loved one’s birthday or where we’ve parked the car—forgetting plays an important role in how we make sense of the world, allowing us to sift through the constant onslaught of sensory information that reaches us every minute of every day. How we sift through this information reflects something about us. We remember more readily those details that align with our worldview, ideas that pique our interest, things that annoy or entertain us. In this way, memory is personal: we remember according to our desires, our values, our needs, our tastes, our attitudes—our version of events.

This malleability of what is recalled has an important, often-overlooked function. The plasticity of memory—shot through with our personalities and skewed to our worldviews—allows us to pull out some strands of our experience and let others slip gently away. Of course, this massaging of the facts happens both purposefully and incidentally: we can actively blur the recollection of unsavoury events in their retelling, filtering in ambiguity and falsehoods that muddy their memory; these edited retellings morphing what is recalled. Or, victims of our physiology, our memories can weather and lose definition over time and, story driven as we are, we fill in the narrative gaps with our own slants. In this way, forgetting and the malleability of memory allow us to be creative with what is remembered, freeing us from the constraints and cruelty of the absolute, fluorescent-lit truth. This wriggle room between fact and recall is crucial, enabling us to weave our and others’ experiences into consistent life stories that we can live with. Over time, these streamlined, remembered versions of events, stories, and lives, are what persist.

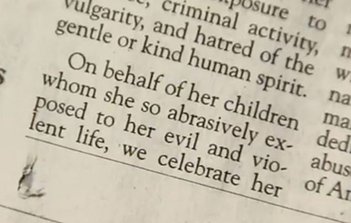

This smoothing of narrative sharp edges is clearly seen in memories of our dead. The stories we tell about those who pass away are softened by our desire to remember our deceased fondly, to honour the lives of those lost, and to pass on the best of these lives to those who will live in their memory. Thus, the stories told about the dead, particularly the long-since dead, are leavened by our capacity to magpie what is remembered, and edit out that which is best left to fade. In this way, forgetting and the malleability of memory lend an important clemency to our memories of our antecedents, shaping positive narrative legacies to be inherited by future generations.

Computer World

Computer World

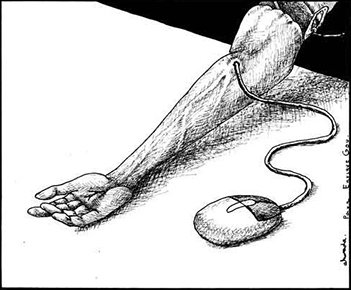

Now, for the first time in history, the fallibility and malleability of human memory is not inevitable. The creation of content in digital spaces has exploded in the last decade with astounding breadth, magnitude and pervasiveness. The means by which we leave our digital footprints online and on digital devices are constantly swelling, with new services and platforms emerging in head-spinning supply. Our digital activities span the full splay of human experience—from finances to foreplay—and every time we go face-to-screen, we contribute to a vast, multimedia archive of data that is changing what it is to remember.

Needless to say, the recording of life using external media is nothing new. Since the earliest hominids, tools have enabled the recording of human experience and activity in different ways, thereby redefining the social and cultural functions of human memory. The evolution of language-based communication, the written word, the printing press, and photographic and film technologies all had sea-changing influences on the recording and retrieval of human memory, altering how it was valued and culturally situated. Since the first human took sharpened flint to dark cave walls, we have been on a trajectory toward the increased externalisation of memory via our tools and technologies. Now, in deeply digital, post-industrial societies, the galloping pace of technological advance has similarly quickened the externalisation of memory.

What marks today’s digital technologies out from past memory-externalising media is the infinity of storage (which removes the need to delete anything), the expedience and ease of information retrieval, and the pervasive use of technologies in every facet of life. This redundancy of deletion, coupled with the fractal detail that can be recorded and retrieved, enabled by our absolute commitment to digital life, means that digital technologies are reaching wider and farther into every dark pocket of human experience than any previous memory-externalisation tool. Because our technologies are our social secretaries, financial advisors, agony aunts, personal shoppers, wingmen, diaries and tour guides, which remember our every link, like, favourite and foible, every day we are committing inordinate tracts of who we are to external memory infrastructures. According to Google’s Eric Schmidt, every two days the human race creates as much information as we did from the dawn of civilisation until 2003, about five exobytes of data. The scope and scale of the information we create and commit to banks of memory is more comprehensive, precise, robust, indelible and accessible than ever before,creating intricate data maps of our activities, thoughts, interests, attitudes, values and locations at a rate that was unimaginable just a few years ago.

The War on Error

The War on Error

Comedian Stewart Lee describes a hypothetical situation in which a mental breakdown leaves him with total amnesia. This memory loss is easily remedied, however, with a quick Twitter search of his name, which generates a minute-faithful dossier of Lee’s movements, company and appearance, as tweeted by his followers, allowing him to “gradually piece everything together that ever happened to me”. Lee bucks at this creepy ethos of recording the minutiae of our lives digitally, describing Twitter as “a state surveillance agency staffed by gullible volunteers…a Stasi for the Angry Birds generation”. It’s a little hyperbolic, but the point remains.

On the excellent BBC radio 4 programme Digital Human, Corey Doctorow, author of blog Boing Boing, described the jumble of what we leave online and on digital devices as “a totally entangled hairball of the important and the unimportant, the daily and the momentous” that can provide an “in-the-round picture of who you are”.

The feverish recording of ours and other’s lives in digital spaces (which already collect huge amounts of information about us), twinned with the use of digital devices to mediate every dimension of life, is changing what it is to remember and disabling what it is to forget (and the likes of which would make the Stasi soil their hosen).

This wholesale digital charting of life in its every detail means that, for the first time in human history—in human memory—remembering, and not forgetting, is now the default. The error that inheres in human memory, so important in streamlining our experiences, memories and narratives, is being corrected, suspended perfectly in the digital formaldehyde.

Death 2.0

Death 2.0

Just as our lives, in digitised societies, are charted technologically, digital technologies are also mediating dying, death, bereavement and memorialisation. Death is becoming desequestered and secularised, the web becoming something of a digital Pompeii populated with frozen renditions of death, to be revisited in time by the living. In novel, wacky and futuristic ways, and the web is changing what will be remembered about our deaths.

Those at the end of life are using technologies to record their experiences of dying, and inform others about the vagaries of dying from particular conditions. The experience of dying and death is also being visually recorded: Angelo Merendino tastefully photographed and posted videos about his wife’s battle with cancer and eventual death. Others upload videos of their loved ones’ last moments, photographs of celebrities’ dead bodies and images of the dead in wedding dresses and Santa suits. A quick internet search will generate horrendous images of civilians killed in conflict, grueling photographs of dictators’ mutilated bodies, and videos of wartime executions (the latter examples I won’t link to). Of course, recording the dead is nothing new; bereft Victorians and Edwardians created keepsakes of their deceased by taking chilling pictures of their propped-up dead, posing with the dead, and staging spirit photography, in which the dead appeared as ghost-like figures. However, the ease with which we can now access, save, copy, send and repurpose this kind of intimate content brings a critical, new dimension to these practices.

Instances of suicide are also being recorded digitally with the posting of suicide notes online, some accompanied by final Instagram photographs taken minutes before the act. Funerals, too, are becoming electric, being recorded and live broadcasted to far-flung relatives. Videos of unorthodox funerals have gone viral and a video of some girls ‘twerking’ beside their friends’ open grave has been viewed by millions. Neither have the dead and dying been spared by the ubiquitous selfie craze: selfies are being taken with the dead, at funerals, with dead grandparents, and with suicide attempts visible in the background.

And of course, our digital spaces are awash with memorials to the dead: in vast digital monuments of Holocaust victims, memorials to miscarried children, commemorative videos, and elaborate memorials in online-gaming worlds built when players die in real life, to name but a few examples.

Linger Longer

Linger Longer

A growing variety of online services are selling the option of creating memories of yourself before you die, allowing you to shape how you will be remembered posthumously. Managing your digital memory is big business. You can curate your post-terrestrial memory by creating a multimedia album of your life, accessed when you are toes up; you can press your ashes into a vinyl on which you can record a personal message or will: ‘a vinyl recording your loved ones will cherish for generations’; or have a QR code cut into your headstone linked to images, video, a biography, or whatever takes your fancy.

A raft of services will allow you to record yourself ante mortem in a variety of heart-rending and hilarious ways, so that you can linger a little longer after death, or pop up unexpectedly in your post-mortem future. You can send out automated messages after you have expired (maybe to tell someone what you really thought of them), send delayed emails years into the future (to your son on his wedding day, decades after your death), and train a programme to tweet like you before you die so it can ‘keep tweeting even after you’ve passed away’. One gamer built a vast virtual world in honour of his deceased wife, in which her avatar lives on and can interact with their son in the game space.

Other services are aimed at minimising the “totally entangled hairball of the important and the unimportant” left behind digitally. Digital-legacy services urge us to prepare for our digital demise, thereby preventing the bereaved from enduring lengthy court battles to gain access to loved ones’ content; navigating labyrinthine terms of service of social media and email providers to gain access; or, perhaps most terrifying of all, sifting unguided through your every email and message, warts ‘n’ all. You can preserve access to your digital legacy using one of many password-archiving services. These will store all your account passwords under a master password, bequeathed to a trustee who gains access when you cease to be. Perhaps, however, you aren’t too fired up by the idea of your poor, grieving mother gawping at your every digital dalliance and draft. In this case, you can create a bespoke action plan to be activated in the case of your cessation. Digital asset-management services allow you to tailor what you leave behind, erasing private or sensitive emails, closing designated accounts, and deleting selected images, video and other content (more examples here).

Sand in the Vaseline

Sand in the Vaseline

Attractive as this notion of a neatly folded digital legacy may be, actual erasure of content in digitised societies has gained a sort of mythic status. Services promising self-deletion, information burial, self-destructing imagery, one-view-only instant messaging, the ability to avoid your friends and send ‘anonymish’ messages are doing a roaring trade, though often their promises are a little empty. Once something enters the digital ether, its source site or profile can be erased, but copies and spin-off content are much more difficult to wipe clean, irrespective of their veracity or relevance—at least not without legal intervention. The possibility for unsavoury, unsanctioned content concerning the dead to crop up postmortem is real, no matter how tight your grip on your legacy. Like sand in Vaseline, it’s so easy to get your information stuck in there, but nigh on impossible to get it out.

Certain online services will even collate your dead loved one’s entire internet activity and presences, sanctioned by them or no, ‘archive[ing] everything you do online’. Though the service quoted, recollect.com, is not specifically aimed at aiding in the archaeology of one’s digital dirt after death, it’s easy to imagine the service being used by the bereaved to gain an all-encompassing view of everything the deceased was up to online. Not all social media sites currently allow the downloading of all account content after a death, some only providing the option of account deactivation. Therefore, these information-collation sites are creating ways of sidestepping such limitations on preserving total digital memory, corralling all of our digital selves, spread across services, rendering them downloadable and searchable.

What can persist after we die is changed utterly by our technologies and, whether curated by the living or the dead, the details of our lives and our deaths that can live on in immortal bodies of data are unprecedented.

Total Recall

At the weird outskirts of this digital-legacy landscape are proposals to reanimate us after death by intelligently mining our digital presences in order to create bespoke digital ghosts. These services promise to create an avatar that looks and sounds like you, that can answer questions about your life, your dreams, your dislikes and hang out and chat with your great-grandchildren. Eterni.me, for example, will ‘learn you’ as you spend time interacting with it while you are alive. What is up for grabs here is virtual immortality, where users can not only curate how they are remembered, but take part in the production of that memory by interacting with future generations in a digital afterlife.

Marius Ursache, CEO of Eterni.me states: “Your grand-grand-children will use it instead of a search engine or timeline to access information about you — from photos and thoughts on certain topics, to songs you’ve written but never published, to family events or your opinions on gay or extraterrestrial marriage (if any)”.

Similarly, MyLifeBits proposes to use data logged throughout the user’s lifetime in order to create a chatbot based on its ‘life logger’. The first life logger, Microsoft’s Gordon Bell, has digitally archived over ten years of articles, books, cards, CDs, letters, memos, papers, photos, pictures, presentations, home movies, videotaped lectures, and voice recordings from his life. This ‘experiment in lifetime storage’ is an attempt to create a surrogate digital brain containing Bell’s life, his memories, his every detail. The proposal is that these lifetime-information stores could be deployed in the creation of postmortem avatars of the life logger, enabling the avatar to emulate the life logger’s personality and experiences with unparalleled accuracy.

Life-like avatars based on real people are already being used to immortalise the experiences of Holocaust survivors using interactive holograms that can answer questions intelligently with the voice, look, mannerisms and memories of the deceased. Spending hundreds of hours being recorded while alive, the dead can tell stories of their childhood and answer complex questions about the meaning of life via these holograms: think SIRI crossed with your great-grandfather.

Virtual immortality services such as these situate human forgetting as a glitch to be corrected. Eterni.me’s mission statement, with the unnervingly glib tagline: ‘Simply Become Immortal’, states: ‘We all pass away sooner or later, leaving only a few memories behind for families, friends and humanity—and eventually we are all forgotten. But what if you could be remembered forever?’.

The Perils of Perfect Memory

All this jockeying for more complete and accurate digital approximations of who we are, to be exhumed after we die, makes me wonder if something is lost when we remember everything and forget nothing. What kind of memories, I wonder, will be handed down when perfect digital memory recalls so very much of our lives and deaths, unleavened by the delusion, spin and poetic license inherent in human memory?

Digital natives, those born into this internet-saturated world, will be the first generation in history whose entire lifetimes—womb to tomb—will be spanned digitally. As the web reaches deeper into every outcrop of human activity, from the most official to the most intimate, how, I wonder, will the availability of such rich, comprehensive, interactive, sound-and-vision archives of entire lives and deaths impact on the remembrance of these net native’s lives in generations to come? We build narratives about the dead, inaccurate and incomplete by design, that cohere into a pattern that appeals to us, taking out bits we don’t like and adding details to bring credence to our version of events. Does comprehensive digital memory signal the end of soft-focus memories of the dead?

Maybe my great-grandfather travelled, not because he was intrepid, but because of a string of failed pursuits at home. Maybe the Cape Town diamond business required him to turn a blind eye to the mistreatment of local communities. Perhaps this cast a shadow on his relationship, his marriage suffering consequent strain. These alternative narratives are entirely hypothetical and, being unable to access any evidence for them, they dip back below the surface of my consciousness and fade away, and I return to the warm, familiar complexion of W.H. O’Connor’s life. Letters and documents from his time have of course survived, stored carefully away in my grandparents’ attic, but nothing like the excruciating, one-click-away detail that would be available had W.H. O’Connor lived the sort of digitally-mediated lives we now do. What persists is the gentler, well-trodden, homespun memory of this man and his life. This memory percolates down into the lives of those of us who follow him, providing us with a positive set of values toward which to strive.

In the full knowledge that this memory is a rose-tinted distillation of W.H. O’Connor’s life, its influence as a piece of social inheritance is no less significant. It creates fertile ground out of which I can grow, unfettered by the failings of my forefathers.

Before the blazing debate about the ‘right to be forgotten’ in the digital age, Bill Callahan sang: “Well everyone’s allowed a past they don’t care to mention”. I tend to agree.It’s an old-fashioned idea, but maybe a little forgetting is not so bad.

Many thanks to Shaun O Connor and Declan McMahon for dead good editing. Thanks also to Vered Shavit, author of blog on digital-era death Digital Dust, for shining a light on this phenomenon with such candour and bravery.