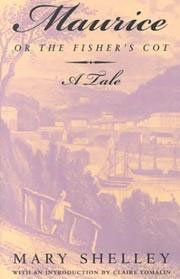

Maurice or The Fisher’s Cot: a long lost tale by Mary Shelley

Maurice is a short three part children’s story by a writer who remains best known for the gothic horror of Frankenstein. I came upon Maurice by accident and I can hazard a guess that I am not the only gothic fiction reader who wasn’t aware that Mary Shelley ever penned a children’s book. She wrote it in August 1820 but sadly, she never published the novel. It was not until 1997 that the literary world rediscovered Maurice. Biographer Claire Tomalin was instrumental in authenticating the manuscript and she wrote a lengthy introduction to the Knopf edition. I would recommend reading the introduction first, even though it does plot spoil, because Tomalin fills in the fascinating family background that underpins Shelley’s story. She explains the connection between Shelley and the woman who unearthed the manuscript, Cristina Dazzi. The rediscovery of Maurice was one of those literary puzzles that turn out to be the genuine article, much to everyone’s delight.

Maurice is a short three part children’s story by a writer who remains best known for the gothic horror of Frankenstein. I came upon Maurice by accident and I can hazard a guess that I am not the only gothic fiction reader who wasn’t aware that Mary Shelley ever penned a children’s book. She wrote it in August 1820 but sadly, she never published the novel. It was not until 1997 that the literary world rediscovered Maurice. Biographer Claire Tomalin was instrumental in authenticating the manuscript and she wrote a lengthy introduction to the Knopf edition. I would recommend reading the introduction first, even though it does plot spoil, because Tomalin fills in the fascinating family background that underpins Shelley’s story. She explains the connection between Shelley and the woman who unearthed the manuscript, Cristina Dazzi. The rediscovery of Maurice was one of those literary puzzles that turn out to be the genuine article, much to everyone’s delight.

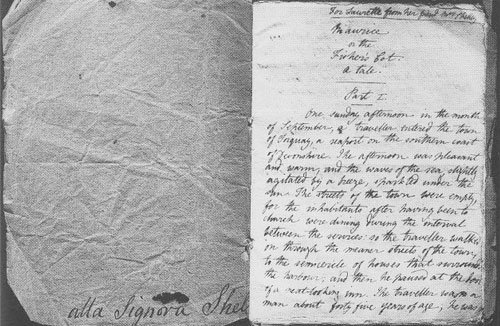

Cristina Dazzi found the handwritten book amongst her family archives in her Tuscan villa. Initially she was not aware of handling anything of importance, ‘A few pages written in an orderly handwriting, tied in two thin bindings with a pale blue cover, which did little to please the eye’ as she later wrote. Then at the top of the first page, Dazzi read this dedication: ‘For Laurette from her friend Mrs Shelley’ and realised that here was something unusual. It must have been an exciting moment for Dazzi, when she finally realised what she had discovered. But what connected the Dazzi family history to that of the Shelleys? Furthermore, who was Laurette and why did Mary Shelley dedicate a book for her?

Shelley’s mother Mary Wollstonecraft was once governess and mentor to the Anglo-Irish Lady Margaret King who became Countess Mount Cashell on her marriage. By 1820, the countess had left her husband with whom she had little in common (also perhaps her republican sympathies inspired by Wollstonecraft) for an Irish poet and classical scholar called George Tighe whom she met while touring the continent. She lived with Tighe in exile in Italy under the name of Mrs Mason. A few years later she went on to give birth to two daughters, Laurette and Nerina; the latter was the great, great grandmother of Cristina Dazzi’s husband. It’s amazing to think of Mary Shelley’s story passed down the family and yet remaining hidden for two hundred years.

Mary Shelley had certainly intended to publish Maurice and she sent the manuscript to her father William Godwin publisher of the Juvenile Library series. However, he told her that he thought the tale was too short to publish. It is indeed short at only thirty-nine pages, although Claire Tomalin points out, ‘It is a small work, but touched with the same spirit as the greater ones it stands among’. In the lovely 1998 Knopf volume the text of the story appears twice, the second time using Mary Shelley’s pagination, spelling, and showing her corrections. The book includes facsimiles of Shelley’s original text in her beautiful handwriting. The publishers have illustrated it copiously with portraits of the Shelley family and their circle. This includes Lord Byron who had an affair with Mary’s stepsister Claire Clairmont and fathered her daughter Allegra.

The story (plot spoiler warning)

Mary Shelley’s story tells of a boy named Henry, stolen by Dame Smithson when he was only two, from his sleeping nurse. Several years later Henry still believes that this woman and her husband are his real parents. After suffering much ill treatment by Mr Smithson, the boy leaves home to search for work. He changes his name to Maurice to avoid discovery and subsequently finds work and refuge with Old Barnet, a fisherman. Barnet is a widower who has lived alone since his wife’s death. The boy lives and works companionably with the fisherman in his old cottage by the sea for a few months until Old Barnet too, dies leaving Maurice once again alone.

Mary Shelley’s story tells of a boy named Henry, stolen by Dame Smithson when he was only two, from his sleeping nurse. Several years later Henry still believes that this woman and her husband are his real parents. After suffering much ill treatment by Mr Smithson, the boy leaves home to search for work. He changes his name to Maurice to avoid discovery and subsequently finds work and refuge with Old Barnet, a fisherman. Barnet is a widower who has lived alone since his wife’s death. The boy lives and works companionably with the fisherman in his old cottage by the sea for a few months until Old Barnet too, dies leaving Maurice once again alone.

A traveller arriving in the village watches Old Barnet’s funeral procession and is curious about the boy he sees following the coffin, ‘Something in the boy’s appearance attracted the traveller’s attention; and once when he ceased crying and looked around towards the inn door, the traveller thought that he had seldom seen so beautiful a youth’. After hearing Maurice’s story from a villager the traveller decides that he will make Maurice’s acquaintance on returning from Exeter, whither he is bound. At that meeting, Maurice tells the kind stranger about the Smithsons and that he needs a new situation. The stranger then tells Maurice about years travelling around to find his son. As he fears he will never find his own son, he offers the boy a home with him and his wife. When the traveller relates the encounter with Dame Smithson where she confessed her child abduction, Maurice joyfully realises that this man is his father. Cue a happy ending all round.

Three Mothers

I enjoyed the fable and I found the depiction of the three maternal characters, Dame Barnet, Dame Smithson and Maurice’s mother particularly intriguing. Claire Tomalin discusses how Mary Shelley interwove the theme of loss into each of their stories. Tomalin points to the sadness in Shelley’s own life; when she wrote Maurice, her son Percy was her only surviving child. Lady Mountcashell had also seen losses in her turbulent life. The countess had been forced give up custody of her seven children when she fell in love with George Tighe. She never saw them again. If you factor in the loss that Claire Clairmont suffered when Byron removed Allegra from her custody and the death of a mysterious child called Elena in 1820 that may or may not have been Percy Byssche Shelley’s then the emotional damage in one small group of people is enormous.

Themes that Shelley must have drawn on were her mother Mary Wollstonecraft’s role as governess and her concern for the lives of the poor. It seems possible that Mary Shelley intended Dame Barnet to be a tribute to her mother and her ideals of education for women and I think that it was a lovely depiction. Dame Barnet is certainly the most sympathetic maternal character in the story. A villager, as a story within a story relates Dame Barnet’s tale:

His dame was so lame that she seldom moved from the old, worsted, high-backed armchair where she used to sit mending the nets, and hearing a few children read, who came to from the neighbouring farmhouses. Our farm is only half a mile distant from the cot and I am one of those who learned to read in Dame Barnet’s great bible. She would not be paid for this, calling it merely a good neighbourly turn; but every Sunday I used to bring her a basket of vegetables and fruits, and every autumn she had a dozen of our best cider.

The villager explained that, ‘all the children about wept at her funeral’. She sounds much like a typical granny, easier going than a hard-pressed parent is. It is not clear from the plot whether the dame has lost her own children or was barren. At any rate she was an excellent mother to all those around her. The picture I have in my mind of Dame Barnet is that of a kindly, even jolly woman, perhaps surrounded by a group of (probably poor) children listening to stories. This image reminded me of a lovely painting that the Impressionist artist Mary Cassatt painted of her mother Katherine reading to three attentive grandchildren.

In contrast, I thought that Maurice’s mother seemed to be almost a blank space. Her husband talks about her affectionately but only briefly. She is described as being both ‘wise and good’ (admirable virtues) but Maurice’s father is central to events. Only the father travels the country searching for news, which is surprising I think. He says, ‘For my part I have never given up hope that I shall one day find him again, for I always felt convinced that he was not drowned’. I wondered whether it was deliberate on the part of the author to make such a vague portrait of an important figure. Could this have its roots in Mary Shelley never having known her mother who died in childbirth? Maurice’s father similarly fails to talk of his own mother as he relates his early history. The traveller refers to his professor father as giving him an education, yet sadly, there is no mention of his mother teaching him his letters. Shelley’s literary father would no doubt have educated his daughter himself so is this also inspired by him? And did Shelley create Dame Barnet in her mother’s image to balance the picture? There seem to be plenty of questions, but nobody can ever know exactly what Shelley had in mind to inspire her characters when she wrote this little book.

In the third part of the book, the traveller relates Dame Smithson’s story. When she first encounters Maurice’s father at the door of her cottage in Ilfracombe she is ‘crying and wringing her hands’ in distress. The Dame explains to him that she has not seen her only son for a year and a half. They exchanged stories and Dame Smithson explained that her recently deceased husband had often beaten her for her failure to conceive. The poor Dame had created an imaginary pregnancy just after her sailor husband’s return to sea. In so doing, she created a seemingly insurmountable problem, which led to her stealing Maurice from his sleeping nurse’s arms. When she realises whom the traveller is she cries, ‘I am the cause of this! I am the wicked woman who stole your child!’

Dame Smithson’s character puzzled me, as Mary Shelley seems to treat her in a very understanding way. Could this be because Shelley had her own experiences of a stepmother when William Godwin married Mrs Clairmont? As a surrogate mother, Dame Smithson was kind and devoted to her boy in contrast to her husband’s unkindness, ‘I have been very miserable as well as wicked: for not only I felt great repentance at having taken this baby from his parents but I found my husband unkinder than ever, and that instead of loving, he perfectly disliked the poor child.’ The dame regarded the boy as her own flesh and blood but she bitterly regretted her actions. She knew that Maurice truly belonged with his real parents and in the quiet happiness of the ending; she was forgiven yet not forgotten.

As I finished the story for the third time, I reflected that Shelley’s subject matter seems rather adult for a child’s story. The grief, violence and loss in the tale are a little heavy going for a ten-year-old child despite the happy conclusion. Dame Smithson took desperate action in hopes of solving her problem and gaining a longed-for child. Even though she has stolen a child, you still feel for her wretchedness and misery. If it is the case that this work reflects aspects of Mary Shelley’s life, then you can see how much the loss of her own children and those of her friend were imprinted on her mind. I am glad to have found Shelley’s book and with it, further ideas for finding out more on Mary Shelley, Claire Clairmont and Margaret Mason. If you don’t know the book, do look out for it; it’s well worth giving it your attention.