A Brief History of Art Forgery in Four Crazy Case Studies

Fraud! Scandal! Forgery! Over the past several years, articles with such attention-grabbing headlines have regularly appeared in the American media, all concerning what is probably the biggest art forgery case of the twenty-first century. A Long Island couple, with the help of a Chinese-born painter, had been selling forged works supposedly by Abstract Expressionist masters such as Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. Since the scheme’s discovery, the art market has been in a state of shock and upheaval, with duped buyers suing, shamefaced experts resigning, and collectors questioning the authenticity of their holdings. The once-prestigious M Knoedler & Company gallery in New York, an unwitting accomplice whose over 150-year history should have made it much more difficult to fool, closed down in 2011 with its reputation in tatters. The author of the forgeries has been identified as Pei-Shen Qian, a Chinese immigrant who claims to have been ignorant about the fact that his works were being sold under false pretenses. (1) One of the masterminds behind the scheme, Glafira Rosales, is cooperating with the authorities, but her boyfriend and co-conspirator, known to authorities as Jose Carlos Bergantinos Diaz, is still at large. (2)

This is hardly the first or most daring art forgery scheme ever uncovered. Art forgery has been taking place in one form or another for centuries. There are almost certainly many unidentified works by known forgers still circulating the art market along with countless others by names we’ve never heard of. According to the late Metropolitan Museum of Art director and expert on fakes Thomas Hoving, up to forty percent of the art he had seen in his museum career was faked, doctored, or misattributed. (3) No matter the perpetrator or the context, forgery schemes always bring up the same few issues and conversations. Should a simple attribution have the power to determine whether a work of art is worth millions of dollars or pennies? How reliable are the so-called experts, when they can be so easily fooled? Why does an artist’s work hang in world famous museums under another artist’s name but cannot find any audience at all when signed with his own? Is the art market foolish, and do collectors encourage others to take advantage of them? As both criminal and civil trails relating to this most recent case continue to make their way through the courts, these questions and others will undoubtedly factor heavily in the discussion. In the meantime, meet five of the twentieth-century’s most notorious art forgers.

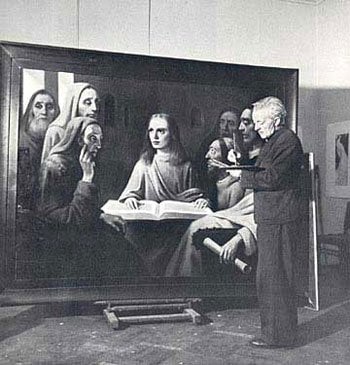

Han van Meegeren (Dutch, 1889-1947) painted works in the style of Dutch Renaissance masters, including Johannes Vermeer, Frans Hans, and Pieter de Hooch. Van Meegeren’s paintings were so successful in fooling scholars and dealers that he was eventually forced to prove to incredulous authorities that he had actually painted them. His notoriety as a forger is largely due to the fact that his painting Christ with the Woman Taken in Adultery, supposedly by Vermeer, ended up in the massive collection of Nazi leader Hermann Goring. Growing up in a traditional Dutch family, van Meegeren had an early interest in art but was discouraged from entering the field. While studying architecture in Delft, he applied for and won a prestigious art award and passed the exams to receive a fine art degree without having ever taken a class. However, he struggled to sell his traditionalist paintings to a primarily avant-garde market and eventually turned to forgery of the artists he most admired. Forgery paid the bills, but anger at the art world for failing to recognize his genius certainly motivated him as well. If revenge was his aim, he succeeded almost beyond belief. His “Vermeers” were adored by collectors, dealers, scholars, and curators, purchased for major museum collections, and revered in scholarly literature. Strangely, van Meegeren’s “Vermeers” were successful despite being visually quite unconvincing when compared with the real ones.

Han van Meegeren (Dutch, 1889-1947) painted works in the style of Dutch Renaissance masters, including Johannes Vermeer, Frans Hans, and Pieter de Hooch. Van Meegeren’s paintings were so successful in fooling scholars and dealers that he was eventually forced to prove to incredulous authorities that he had actually painted them. His notoriety as a forger is largely due to the fact that his painting Christ with the Woman Taken in Adultery, supposedly by Vermeer, ended up in the massive collection of Nazi leader Hermann Goring. Growing up in a traditional Dutch family, van Meegeren had an early interest in art but was discouraged from entering the field. While studying architecture in Delft, he applied for and won a prestigious art award and passed the exams to receive a fine art degree without having ever taken a class. However, he struggled to sell his traditionalist paintings to a primarily avant-garde market and eventually turned to forgery of the artists he most admired. Forgery paid the bills, but anger at the art world for failing to recognize his genius certainly motivated him as well. If revenge was his aim, he succeeded almost beyond belief. His “Vermeers” were adored by collectors, dealers, scholars, and curators, purchased for major museum collections, and revered in scholarly literature. Strangely, van Meegeren’s “Vermeers” were successful despite being visually quite unconvincing when compared with the real ones.

When one of van Meegeren’s Vermeer copies was found in Nazi possession, he was arrested for treason, as it was believed that he had sold a Dutch national treasure to the enemy. Faced with execution if convicted, van Meegeren admitted that the painting was actually his own and was forced to prove his claim by painting another, similar one. He was sentenced to a year in jail for forgery but died of a heart attack before he could serve time. Undoubtedly due to the sensational nature of his World War Two connection, there is more literature on van Meegeren than on most other forgers, and he is also mentioned in almost all literature on other forgers. (4)

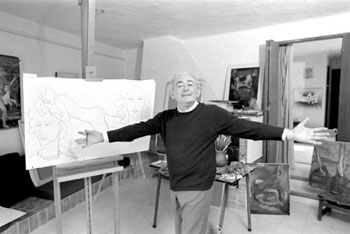

Elmyr de Hory (Hungarian, 1906-1976) made an unusually large body of drawings and paintings in the style of Modernists like Pablo Picasso, Raoul Duffy, and Henri Matisse. The son of a wealthy Hungarian family, de Hory studied art in Munich and Paris and ran in European Modernist circles with the likes of Fernand Léger before being left penniless and stateless by World War Two. De Hory had ambitions of being a painter in his own right, but he was never successful despite several gallery shows and turned to forgery to make ends meet. While he seems to have been somewhat bitter about the fact that he struggled to sell art under his own name, ideology was not his overriding motivation. He attempted to return to a legitimate painting career several times but ended up relapsing once he had invariably exhausted his finances. He eventually teamed up with con men Fernand Legros and Réal Lessard, who acted as his selling agents but also often pocketed most of the profits. It was Legros and Lessard’s personal and professional antics that eventually got all three into trouble. The fact that de Hory’s operation had taken place in many different countries throughout Europe and the Americas, combined with his stateless status, many pseudonyms, and the lack of extradition treaties between certain countries, made it difficult for any one country to build a case against him. He ended up serving two months jail time in Ibeza, Spain for a number of minor charges and afterwards spent several years trying to live as a legitimate painter. When French authorities finally attempted to extradite him, he committed suicide. De Hory was the subject of the 1973 Orson Welles’s documentary F is For Fake. (5)

Elmyr de Hory (Hungarian, 1906-1976) made an unusually large body of drawings and paintings in the style of Modernists like Pablo Picasso, Raoul Duffy, and Henri Matisse. The son of a wealthy Hungarian family, de Hory studied art in Munich and Paris and ran in European Modernist circles with the likes of Fernand Léger before being left penniless and stateless by World War Two. De Hory had ambitions of being a painter in his own right, but he was never successful despite several gallery shows and turned to forgery to make ends meet. While he seems to have been somewhat bitter about the fact that he struggled to sell art under his own name, ideology was not his overriding motivation. He attempted to return to a legitimate painting career several times but ended up relapsing once he had invariably exhausted his finances. He eventually teamed up with con men Fernand Legros and Réal Lessard, who acted as his selling agents but also often pocketed most of the profits. It was Legros and Lessard’s personal and professional antics that eventually got all three into trouble. The fact that de Hory’s operation had taken place in many different countries throughout Europe and the Americas, combined with his stateless status, many pseudonyms, and the lack of extradition treaties between certain countries, made it difficult for any one country to build a case against him. He ended up serving two months jail time in Ibeza, Spain for a number of minor charges and afterwards spent several years trying to live as a legitimate painter. When French authorities finally attempted to extradite him, he committed suicide. De Hory was the subject of the 1973 Orson Welles’s documentary F is For Fake. (5)

Artist John Myatt (British, b. 1945) and con man John Drewe (British, b. 1948) together perpetrated a particularly bold and complex operation, faking works by European Modernists such as Alberto Giacometti, Ben Nicholson, and Marc Chagall. Posing as a rich, well-connected patron of the arts, Drewe built relationships with such prominent British arts institutions as the Tate Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum. By donating money and paintings to such institutions, Drewe won the trust, respect, and gratitude of important scholars and curators. By establishing his reputation as a prolific and knowledgeable collector, Drewe transformed himself into a well-connected benefactor of the British art community, and therefore his own best tool of deception. Even more daringly, Drewe gained access to the libraries and archives of these museums and used them to build detailed provenances for the works he attempted to sell, even altering auction records and dealer catalogs. While other forgers have attempted to create provenance through doctored receipts and stories of dead aunts with attics full of old paintings, Drewe went to the most trusted sources of provenance information – those counted on to unmask cons like his – and altered them to fit his needs. When his scheme was discovered, the integrity of some of the best libraries and archives was seriously and frighteningly thrown into doubt. Drewe was eventually sentenced to six years in prison but only served two. He has continued to proclaim his innocence, maintaining that he was framed and appealing his sentence several times. Upon release, he has gone right back to running a host of crazy schemes.

Artist John Myatt (British, b. 1945) and con man John Drewe (British, b. 1948) together perpetrated a particularly bold and complex operation, faking works by European Modernists such as Alberto Giacometti, Ben Nicholson, and Marc Chagall. Posing as a rich, well-connected patron of the arts, Drewe built relationships with such prominent British arts institutions as the Tate Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum. By donating money and paintings to such institutions, Drewe won the trust, respect, and gratitude of important scholars and curators. By establishing his reputation as a prolific and knowledgeable collector, Drewe transformed himself into a well-connected benefactor of the British art community, and therefore his own best tool of deception. Even more daringly, Drewe gained access to the libraries and archives of these museums and used them to build detailed provenances for the works he attempted to sell, even altering auction records and dealer catalogs. While other forgers have attempted to create provenance through doctored receipts and stories of dead aunts with attics full of old paintings, Drewe went to the most trusted sources of provenance information – those counted on to unmask cons like his – and altered them to fit his needs. When his scheme was discovered, the integrity of some of the best libraries and archives was seriously and frighteningly thrown into doubt. Drewe was eventually sentenced to six years in prison but only served two. He has continued to proclaim his innocence, maintaining that he was framed and appealing his sentence several times. Upon release, he has gone right back to running a host of crazy schemes.

Drewe’s back story is rather unclear, as he has invented many fake identities and histories for himself and tells elaborate, complex, and wildly-improbable stories. However, it appears that he has no art background. Since he has never actually admitted to committing a crime, he has not exactly been forthcoming about his motivations for doing so. John Myatt, meanwhile, had art school training in England and briefly attempted a career as an artist. He had short-lived success as a musician, but was a single father of two barely supporting his family by painting legitimate reproductions of old masters when Drewe found him and began ordering “in the style of” paintings from him. Myatt was not initially a knowing participant in the crime but slowly realized over time what Drewe was doing with his work. The desperate need for money was the motivation for his later participation as a knowing collaborator, but also fear eventually played a role. Myatt served four months of a one-year sentence for conspiracy to defraud. Since being released in June 1999, he has done quite well for himself by teaching, painting both legitimate reproductions and original works, giving interviews, and consulting for law enforcement officials. By Myatt’s own testimony, some of his works are still on the market with their fake attributions, but he feels it best for everyone that he does not bring attention to them. (6)

Ken Perenyi (American, b. 1949) had an unusually varied output for a forger. While most tend to master a single era, genre, or style, Perenyi was able to paint convincingly as a wide variety of British, continental European, and American artists, including Martin Johnson Heade, James Buttersworth, and Charles Bird King. This is particularly impressive because Perenyi has no formal art school training. A high school dropout in 1970s New Jersey, Perenyi became involved both in art and in the occasional criminal enterprise through a group of wild-child friends led by artist Tom Daly and his associate Tony Masaccio. He also received training from a period of employment in an art restorer’s studio and through the many artists, collectors, and dealers he befriended throughout his career. Perenyi dreamed of becoming an artist in his own right but was foiled several times through a variety of unfortunate circumstances. He was good at painting in the styles of other artists and used that talent as a means of supporting himself when he had few other options. Perenyi’s career took him throughout the United States and eventually to England, and at one point he became quite wealthy. In an effort to prevent anyone from connecting such diverse forgeries back to the same source if any were questioned, he worked with many partners, including friends, neighbors, other artists, and career con men. He also sometimes did legitimate restoration work and traded in real art and antiques, both as cover for his other activities and as another source of income. Despite his careful efforts to keep his own name and face clean, Perenyi came very close to being arrested in the late 1990s and early 2000s, but his case was abruptly dropped for reasons still unknown. After the statute of limitations ran out, Perenyi wrote a memoir about his experiences. (7)

Ken Perenyi (American, b. 1949) had an unusually varied output for a forger. While most tend to master a single era, genre, or style, Perenyi was able to paint convincingly as a wide variety of British, continental European, and American artists, including Martin Johnson Heade, James Buttersworth, and Charles Bird King. This is particularly impressive because Perenyi has no formal art school training. A high school dropout in 1970s New Jersey, Perenyi became involved both in art and in the occasional criminal enterprise through a group of wild-child friends led by artist Tom Daly and his associate Tony Masaccio. He also received training from a period of employment in an art restorer’s studio and through the many artists, collectors, and dealers he befriended throughout his career. Perenyi dreamed of becoming an artist in his own right but was foiled several times through a variety of unfortunate circumstances. He was good at painting in the styles of other artists and used that talent as a means of supporting himself when he had few other options. Perenyi’s career took him throughout the United States and eventually to England, and at one point he became quite wealthy. In an effort to prevent anyone from connecting such diverse forgeries back to the same source if any were questioned, he worked with many partners, including friends, neighbors, other artists, and career con men. He also sometimes did legitimate restoration work and traded in real art and antiques, both as cover for his other activities and as another source of income. Despite his careful efforts to keep his own name and face clean, Perenyi came very close to being arrested in the late 1990s and early 2000s, but his case was abruptly dropped for reasons still unknown. After the statute of limitations ran out, Perenyi wrote a memoir about his experiences. (7)

NOTES: (1) Qian speaks about his role in the operation in Lawrence, Dune and Wenxin Fan. “The Other Side of an $80 Million Art Fraud: A Master Forger Speaks”. Bloomberg Businessweek. 19 Dec, 2013. http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2013-12-19/the-other-side-of-an-80-million-art-fraud-a-master-forger-speaks (2) Qian, Rosales, and Diaz sources: Dune and Wenxin. “The Other Side of an $80 Million Art Fraud”. Cohen, Patricia. “Suitable for Suing”. New York Times. 26 Feb, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/26/arts/design/authenticity-of-trove-of-pollocks-and-rothkos-goes-to-court.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0 . Rashbaum William K. and Patricia Cohen. “Art Dealer Admits to Role in Fraud”. New York Times. 17 Sept, 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/17/arts/design/art-dealer-admits-role-in-selling-fake-works.html . (3) Hoving is quoted in Salisbury, Lanie and Aly Sujo. Provenance: How a Con Man and a Forger Rewrote the History of Modern Art. New York: Penguin Press, 2009. 236. (4) Van Meegeren sources: Dolnick, Edward. The Forger’s Spell: A True Story of Vermeer, Nazis, and the Greatest Art Hoax of the Twentieth Century. New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2008. Wynne, Frank. I Was Vermeer: The Rise and Fall of the Twentieth Century’s Greatest Forger. New York: Bloomsbury, 2006. (5) De Hory sources: Irving, Clifford. Fake! The Story of Elmyr de Hory the Greatest Art Forger of Our Time. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1969. Written during the artist’s lifetime, Irving’s book draws extensively on de Hory’s own recollections. Information about the end of de Hory’s life comes from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elmyr_de_Hory . (6) Myatt and Drewe sources: Salisbury and Sujo. Provenance.Myatt has also given many interviews on the subject, including Dolnick. The Forger’s Spell. 66-76. Myatt’s thoughts on his extant works are discussed in Salisbury and Sujo. Provenance. 303-304. (7) All of the information about Perenyi comes from his own account of events in Perenyi, Ken. Caveat Emptor: The Secret Life of an American Art Forger. New York: Pegasus Books, 2012.