Why are there Poor People? Sam Bowles and the Poverty Dilemma

Professor Samuel Bowles has tried to change the conversation over human behaviour. But his battle has been a long and profound journey that spans continents. Francois Badenhorst went to Santa Fe, New Mexico to speak to the man and the maverick.

Professor Samuel Bowles is arched over his laptop when I walk into his office, typing intently. From his window, you can see a stunning vista, the adobe buildings of Santa Fe look like rock formations from this vantage point. His office sits in pod 3 of the Santa Fe Institute, a non-profit academic research institute that draws great minds from across the world. The usually barren hills of New Mexico in which the building is nestled are a dazzling green thanks to the unseasonal summer rain.

Bowles – or just Sam, as he likes to be called – is clearly not that worried about the rain. Slim and in great shape for a 73 year old, his cycle helmet lies on his desk. His work attire of a t-shirt and shorts further punctuate his relaxed, loose collar approach to academia. At the Institute, he is the head of the Behavioural Sciences department. But it is almost impossible to pin down Sam Bowles to one field: Part economist, part politician, part evolutionary theorist.

But all of it coalesces into Bowles’s true quest: To Elucidate the price of inequality in society and to prove Homo Sapiens intrinsic desire for fairness and justice. And it has been an uphill battle: The field of Economics has long been dominated by the neoliberal, “invisible hand” school of thought. And evolutionary biologists have, again and again, underscored what Richard Dawkins termed “the selfish gene”. It was never going to be an easy fight, but Bowles has stayed the course throughout his career.

*

Sam Bowles’s journey to contrarian academic is undoubtedly rooted in his unusual upbringing. He was born in New Haven, Connecticut in 1939 to an influential family. His father, Chester, had made his fortune in the advertising business and parlayed his business success into a political career which culminated in his appointment as the U.S ambassador to India.

And this is where Bowles spent his formative years, he and his sister were the only foreigners in the school they attended. The endemic poverty of the locals became immediately apparent to the young Bowles. “I came from a town where there were exactly 2 poor families – I knew them because we all went to school together,” says Bowles. “But then I went to India and the whole country is poor, just about.” It was a fact that Bowles struggled with immensely. “Added to that experience is me realising at the age of 11 that I was not particularly outstanding at anything in my school – either in academics or sport.”

It was Bowles’s first exposure to the vast inequality that is found across the world. Moving from the affluent and sheltered liberal academia of New Haven, Bowles was confronted with a question that he never even knew existed. “As kids do, I was competing with them and I wasn’t doing very well. So you didn’t have to be a genius to go,‘Well, what the hell is going on here?’”

It was a desire that fuelled Bowles’s studies. But he was never able to attain the answers that had plagued him, even after he concluded his studies at Yale and Harvard. “Fifteen years and a PhD in Economics later, I don’t think I was any closer to the answer to the question I asked my mom when I was 11, which is, ‘How come they are so poor?’ given that they are just like us.

“My evolution as a scientist really had a lot to do with that question.”

*

In the 1960’s, Bowles had been a part of the movement that mathematized Economics. It was ground breaking work, and to this day, it is something Bowles is proud of. “My courses may have been the first in the US, maybe anywhere, that used mathematics and problem sets for Economics students. I soon became quite hated by grad students across the country.”

As he speaks about it, a smile bursts across his face. “Eventually, I published them as a book. I remember I was speaking at an anti-Vietnam war rally in Pittsburgh and some guy came up to me and said, ‘There’s a guy that has your same name and he’s a complete asshole. You won’t believe the book he wrote!’” His laughter is infectiously warm, but it is understated, filling the room like rising flood water.

But Bowles also admits that his work has been a sword and a plough share. “So yeah, I was a part of the process of mathematizing the discipline – which I’m very glad happened – but given what we were doing, we were narrowing it,” says Bowles. His outstanding work had inadvertently moved Bowles further away from the question that he always wanted to answer. “Increasingly during the 50’s and 60’s the questions became narrower. And so what was hot in Economics wasn’t answering these big questions of social importance.”

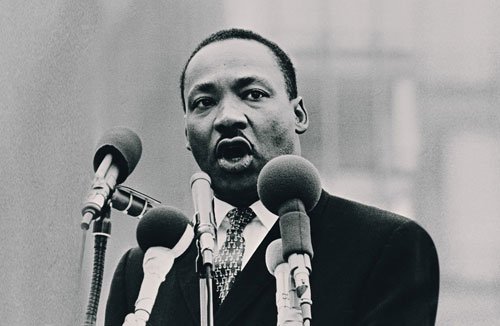

Sam Bowles was teaching Economics at Harvard – an academic dream job – and yet he was deeply frustrated. He had thought of quitting – “Maybe journalism, I told my wife” – when Dr Martin Luther King Jr. approached him for help. It was an utterly transformative event. The year was 1969, and America was in turmoil. While American GI’s were losing their lives in the inhospitable jungles of Vietnam, America’s racial inequality had reached boiling point.

“He asked me, among a few others, for my help during his Poor People’s march and I said, “OK, if Martin Luther King asks you something, you better try to answer it,” says Bowles in his affably relaxed voice. What King had wanted to know is exactly what 11 year old Sam wanted to know: Why are some people poorer than others? “It was quite shocking: I mean, you have your PhD in Economics and you did well enough to get a job at Harvard, but you are still unable to answer economic questions of great interest, they weren’t idiosyncratic at all, Dr King’s questions were absolutely predictable questions about inequality in America. That really pushed me a lot.”

“I realised that, ‘Wow, you can use Economics to answer some pretty important questions’. So I stuck around instead of leaving the discipline. I decided to try and change economics.”

*

Imagine that someone hands you one hundred Rand. It’s yours, but there’s one condition: You must share it with another person. How much you choose to share is up to you. But if the other person – who is cognisant of the R100 amount – rejects the offer, you leave with nothing.

This is the Ultimatum game. And when it is played in an academic test setting, people nearly always share equally. More telling, is that when the person who must share tries to be greedy (maybe trying to give 25 while keeping 75), he or she is inevitably always punished by the other via rejection.

It’s a result that fascinated Bowles. “When I first heard about the Ultimatum game, I thought “Wow, people were willing to spend money to send the jerk home with nothing in his pocket. The Ultimatum game showed that people really do not like injustice, they are willing to pay to put an end to it.” That is, I am willing to give up the 25 rand you have offered me, just to punish your attempt at unfairly distributing the money.

It was at this junction in the 1970’s where Bowles concentration started to segue into the Behavioural Sciences; or, as he likes to term it, “Behavioural Economics”. Altruism, in particular, became Bowles’s greatest concentration.

“I wrote a book called ‘A Co-operative Species’. And to write that book I had to overcome vast opposition among economists and biologists that evolution could produce a co-operative and altruistic animal,” he explains. “That is really quite a prejudice on their part, I mean the idea that genes are thought of as things that maximize their own fitness. As Richard Dawkins said, ‘the selfish gene’.

“I wrote a book called ‘A Co-operative Species’. And to write that book I had to overcome vast opposition among economists and biologists that evolution could produce a co-operative and altruistic animal,” he explains. “That is really quite a prejudice on their part, I mean the idea that genes are thought of as things that maximize their own fitness. As Richard Dawkins said, ‘the selfish gene’.

“There then follows in Dawkins work a non-sequitur that a selfish gene gives rise to selfish people – that’s false.” What Bowles is referring to is group selection. Traditional Darwinism presupposes that individuals act selfishly, and that this is favourable over group oriented altruistic behaviours. That is, individuals who place an emphasis on maximizing their own reproductive potential above all others will be more successful. “If you have two groups, one which consists mainly of altruists who largely co-operate with each other, and they are competing for some reproductive resource, like land, with another group of people who are self interested, well you don’t have to be a genius to figure out who is going to win.”

But altruism is not really that simple. “In a world where self interest is assumed, there is a tendency to think everything that isn’t self interest is altruism,” says Bowles. Just as self interest has been simplified and universally applied, the same has happened to altruism.

“Think of all the ethical reasons for acting according to the social norm, I’m honest because it would harm somebody if I were dishonest – and that could be considered a form of altruism because I’m weighing their harm in my thinking. But it could also be that I’m honest because I would like to be an honest person.” This means that we often do good things because it makes us feel good.

The misappropriation of altruism has a lot to do with the shake-up of traditional evolutionary thought in the past twenty years. Indeed, led in part by people like Sam Bowles. Like with anything, if you remove the previously held certainty of a situation, people yearn to fill that gap. “We always had Homo Economicus, and then suddenly Homo Economicus is dead, long live Homo who? Homo X. And people constantly try to fill in that x. Altruisticus and Reciprocans and all these other names, right?” says Bowles, he is now in full flight as he explains this. “But maybe it’s the wrong thing, maybe the ways in which we are altruistic and fair minded are multiple, and that’s what it looks like in the experiments.”

Simply put, we are psychologically a deeply complex species: To assign the broad range of human experience to merely two simplistic and opposing evolutionary substrates is not enough. And what’s more, it’s simply wrong.

Bowles’s work has also touched on another interesting point. “Pure altruism – meaning helping others at a cost to myself irrespective of my opinion about your type – is rather rare. Much more powerful is what Bowles terms “conditional altruism”. “If I see you acting generously towards a third party and I know you are OK as a type, then I’ll treat you as being a part of my ethical world and I’ll help you.”

*

Sam Bowles is a man in demand; he has a conference soon and must leave me. But before he goes he says something illuminating. As I leave his office, he says, “It depends what your project is as a scientist, and mine has always been to answer the question I asked my mom. And I’ve always tried to do something about it.”

Sixty-two years on, Sam Bowles’s mind still returns to India. And it has driven him. It has led him from Economics to social activism to Behavioural Sciences. To understand the unfairness and cruelty of the inherent inequality he noticed as an 11 year old has been his raison d’être. And later, this evolved into a battle to reclaim our complex and special humanity from constrictive academic thought.

Bowles’s work has provided us with a profound, and rather beautiful, way to look at our natures. “Every day we are reconstructing ourselves,” he says. “We make ourselves over daily – not only in the eyes of others – but also for ourselves.”