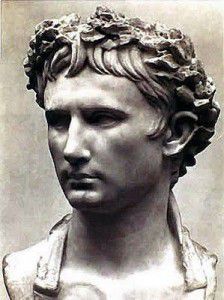

Augustus: The First Roman Emperor.

Imperator Gaius Julius Divi Filius Caesar Octavianus

Imperator Gaius Julius Divi Filius Caesar Octavianus

The future emperor is born.

The first emperor, commonly known as Augustus, was born Gaius Octavius in the year of the consulship of Hibrida and Cicero (63 BC or 691 Ab Urbe Condita). He was born to Gaius Octavius (Senior) and Atia Balba Caesonia, two respectable members of Roman society. His father, G. Octavius, had become a member of the senatorial elite thanks in part to Sulla’s laws that allowed Quaestors to become full members of the senate upon taking office. His mother was the nephew of Julius Caesar who was at that time a rising member of society with great ambition, therefore, the future Augustus was born into a prominent family with many great connections that would serve him well later on in life.

Gaius Octavius senior died when the future emperor was only four but soon enough, his mother remarried into another influential family. This L. M. Philippus, Octavian’s stepfather, was to become consul and remain loyal to him throughout his entire life, which was something that the future emperor would never forget.

Gaius Octavian had a typical Roman childhood education. He learnt the classical languages of Latin and Greek and with that, oratory. He learnt how to ride a horse, to read and to write, and how to fight to some degree. By the time he was ten years old, he caught the eye of his great uncle G. J. Caesar because of the funeral oration he gave at his grandmother’s funeral (who was sister to Caesar).

On October 18, 48 BC, Octavian officially became a man by donning the toga irilise and performing the ‘coming of age’ ceremony. He was now able to embark on a career of his choosing to which this subsequently became a public one. Now that Caesar had become the sole ruler of the Roman republican empire, Octavian was to rise high. At first becoming Pontiff, and consequently a Praefectus Urbi (whose role had diminished throughout the years and had, by Octavian’s time, become honorary).

Octavian and Caesar became exceptionally close during Caesar’s final years. Caesar had recognised something great in Octavian and used him to maximum effect. Although unable to become an exceptional military leader because of his reccurring illnesses, Octavian was adept at provincial management and politics, as well as oratory. He soon gained the complete trust of his great uncle Caesar, and in the last few months of Caesar’s life, he had named Octavian as his main heir.

With an eye for the future, Octavian’s great uncle had sent him to Apollonia, to study the tactics and strategies of war as well as furthering his knowledge on provincial administration and academic studies. In addition, Octavian had been sent there so as to become a future military leader, for Caesar had in mind to invade Parthia and stationed in Macedon was a total of around five legions (plus auxiliaries). However, Caesar’s assassination foiled the plan of invasion. Octavian had heard of his adoption by Caesar in the latter’s will, so the young man travelled to Italia to claim the inheritance left to him by his now deceased adopted father.

When Octavian had arrived in Italia, he was welcomed by loyal Caesarion troops but, knowing that Caesar’s fortune was not forthcoming because Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony) was withholding the fortune from him, Octavian (who now called himself Gaius Julius Caesar after his adoptive father) ordered 700 million sesterces that was to be used for the Parthian war to be paid to him instead. With the money and support of many Caesarion veterans, Octavian was able to gain more supporters and soldiers under his command.

This was the initial conflict between him and Antonius. Whilst Octavian was building up his own army. Marcus Antonius was trying to build up political support but he was struggling because he was making many enemies in Rome who believed that Antonius was an effeminate drunkard. Soon enough, Antonius had passed a law which granted him the province of Cisalpine Gaul and at once departed with an army to take it from the then current governor, D. J. Brutus Albinus (not to be confused with the more important Marcus Junius Brutus), one of Caesar’s assassins.

In response to Antonius’s siege of Brutus Albinus’ capitol of Mutina, because the latter had refused to give up his governorship, the senate gave Octavian his first opportunity at command on a large scale. The senate had no choice. Octavian was the only man in Italia who had an army and the senate could not rely on bringing legions abroad for they would take a long time to muster. Therefore, the consuls Hirtius and Pansa lead the army of the Republic along with Octavian. The confrontation between the two consuls, Octavian, and their enemy Antonius, resulted in Antonius’s defeat at the battle of Forum Gallorum. However, during the battle, the two consuls were killed which left Octavian the only commander who could claim the victory and carry on the war.

In response to Antonius’s siege of Brutus Albinus’ capitol of Mutina, because the latter had refused to give up his governorship, the senate gave Octavian his first opportunity at command on a large scale. The senate had no choice. Octavian was the only man in Italia who had an army and the senate could not rely on bringing legions abroad for they would take a long time to muster. Therefore, the consuls Hirtius and Pansa lead the army of the Republic along with Octavian. The confrontation between the two consuls, Octavian, and their enemy Antonius, resulted in Antonius’s defeat at the battle of Forum Gallorum. However, during the battle, the two consuls were killed which left Octavian the only commander who could claim the victory and carry on the war.

In the end, Octavian had demanded the consulship to be rewarded to him but when this was refused he marched on Rome and was thereafter elected to the consulship. Within a short period, news arrived that Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus had rallied around themselves numerous legions, auxiliary troops and allies, in an attempt to destroy Octavian and Antonius separately and ‘restore the Republic’. These two men were relatives by marriage, and also shared the same ideologies. They had both participated in the assassination of G. J. Caesar and both wished to restore the authority of the senate and republic. As Octavian was Caesar’s main beneficiary (who had now named himself after his deceased adoptive father), he was considered a prime target of Brutus and Longius. In addition, Antonius was loathed by Longinus and Brutus and it was apparent that the former was another target for the two men.

However, instead of believing that Brutus and Longinus would be fighting the two men separately, Antonius and Octavian, along with Lepidus who had joined Antonius sometime previously, formed an alliance to work together to defeat their mutual enemies. This alliance has gone down as ‘The Second Triumvirate’.

This alliance caused a huge shock throughout the Roman west (where the three men were based). This was mostly due to the fact that the triumvirate were now badly in need of more troops and the only way they could do this was to raise funds from the rich and the only way for that was to proscribe, as Sulla had done previously.

Throughout the rest of the year, the three men assassinated their political enemies but also included many rich equestrians and plebeians so that they may secure their wealth and use it for their own purposes. Approximately 2000 members of the rich senators and equestrians were purged and their wealth taken. This money was heavily invested into raising a force capable of fighting Brutus and Longinus’ own force, which was thought to be over 75,000 strong.

The resulting armies met at Philippi where the armies of Brutus and Longinus were completely destroyed. Moreover, Brutus and Longius had lost their lives in the conflict. The victory ensured Octavian, Antonius, and Lepidus, as the supreme magistrates in the Roman world. Between them, they carved up the Roman Empire as their own personal administrative ‘empires’. Lepidus gained Africa and a few minor provinces in Hispania whilst Octavian gained the remaining western possessions including; Gaul, Italia, Sicilia, and the majority of Hispania. Antonius secured the rich eastern lands, making Egyptus his base of operations.

After the battle of Philippi in 42BC, the triumvirate effectively ruled the republic of Rome in their prospective provinces. Octavian, now 21 years old, was one of the most successful politicians the Roman world had seen. For a brief few years thereafter the battle, he enjoyed peace where he administered his various provinces, sent out governors, raised money for the treasury and recruited more soldiers to his legions. However, that peace was not to remain for long.

Within three to four years of ending the fight against Brutus and Cassius, Octavian was now at war with Sextus Pompey, the son of Caesar’s great friend and enemy Pompey Magnus.

Sextus had refused Italia grain shipments to pass by Sicilia before, and now, with all of Octavian’s opponents either dead or fled abroad, he and the other triumvirate members felt ready to deal with S. Pompey once and for all. The resulting conflict brought Octavian’s friend M. V. Agrippa at the helm of Octavian’s forces. Octavian and Agrippa launched two separate attacks against Sextus while Lepidus came up from Africa with his own navy. Octavian, admittedly not being the most capable of generals, failed in his attempt to invade Sicilia but his friend and General, Agrippa, won a major victory against Sextus at the battle of Naulochos. This caused the forces of Sextus to abandon him, and he himself abandoned Sicilia. Sextus was later captured and executed without trial by one of Antonius’s commanders.

With Sicilia firmly under the triumvirate’s control, a political move by Lepidus was thwarted by Octavian which caused the former’s demise as a politician. Lepidus had felt disappointed in the arrangements given to him by the distribution of provinces when the triumvirate first formed their alliance. He had raised a large number of fleets and armies to aid in his partners’ defence and wars abroad and he felt that Sicilia was rightly his. Therefore, he tried to convince his soldiers, and his partners that Sicilia was rightly his own territory but at that moment he had overreached himself. Without a doubt Octavian saw an opportunity to gain more territory and eliminate a political opponent and immediately told the senate that Lepidus was trying to usurp power and launch a revolt against Rome. This had an immediate effect on Lepidus’s position. His soldiers were largely bribed by Octavian to join with his own forces and Lepidus quickly lost political and military support and was at once exiled to a villa in Italia where he was forced to resign all titles except the position of Pontifex Maximus.

Octavian took the provinces previously held by Lepidus and sent loyal governors to administer them. Octavian now ruled the whole of the western Roman republic. He secured the grain shipments to Italia and once again dominated the Roman military and political scene. From a mere teenager into a fledging young man, he had risen far above what many men of more experience had gained in a lifetime. He styled himself as ‘Gaius Julius Caesar, son of a god.’ Which made the majority of people in the west recognise his claim where his adoptive father had left off.

An extraordinary man in his own right; he was capable of committing great crimes of cruelty against his fellow citizens to get what he wanted but throughout his tenure of the west, he had governed it well and highly enriched those provinces. By 35 BC after the rebellion of Sextus and of Lepidus’s exile, Octavian was firmly in control and the world knew that only one man remained who was set against him, and that was his most detestable enemy, Marcus Antonius.